Catch up on Part I of this fascinating interview here.

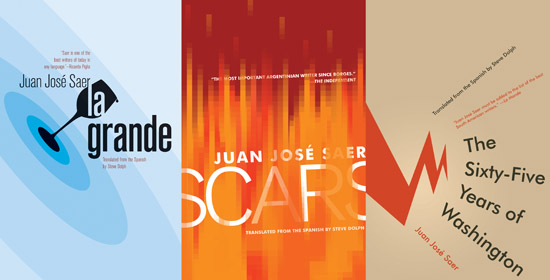

Steve Dolph is the translator of three books by the late Argentine novelist Juan José Saer, who died in Paris in 2005. All three were published by Open Letter Books, the most recent (June ’14) being Saer’s final, unfinished novel, La Grande. Mr. Dolph is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Hispanic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, where his research treats Renaissance ecopoetics and the pastoral tradition. His most recent translation, of Sergio Chejfec’s “El testigo” / “The Witness,” is available in the July 2014 issue of Asymptote.

Jeremy Davies: I seem to recall reading, third hand, of Saer demolishing, in Le Monde, an apologist article by Vargas Llosa, likewise in Le Monde, in which the latter more or less put forward the notion that everyone should just “forgive and forget” regarding the “disappearances”… Are you familiar with that altercation?

Steve Dolph: I’m not familiar with that particular polemic, but it’s not surprising. It’s indicative of a wider dispute among Argentines. Many people would like the period of recrimination and memorializing to come to a close, while others see that gesture as a kind of tacit acceptance and even condoning of the violence. If Saer responded strongly to a plea to “forgive and forget” or even simply to accept that “what’s done is done,” my guess is that it’s at least partly because he didn’t believe the past really could be left behind at all. His novels suggest that he was fundamentally suspicious of the concept of “the past” as such, despite his sense that that’s where everything seems to be. If I were a serious scholar of Saer’s work, which I can’t pretend to be, I might be able to say more about the intersection of politics and philosophy in his writing. What’s apparent, even from a lay perspective, is that the late ’60s and early ’70s, when Saer came of age as a writer and intellectual, were a time when these two fields—politics and philosophy—developed a unique relationship. Which is to say, it may be hard to disentangle his ostensibly “political” writing, as in the piece you mention, from the more philosophically oriented work in his novels.

Could you speak at all about what part character plays for Saer, then, in this universe where not only fiction but consciousness itself is called into question? That is, who are these people (or “people”) who populate so contingent a universe and yet whom Saer takes such pains to distinguish one from the other and invest with history, charm, and opinion? I find it a little difficult to credit the notion that they are surrogates for Saer, strictly speaking, yet, at the same time, the Garay twins (the one who “escapes” and the one who “disappears”) are hard not to see in that light; and you make a good case for Nula and Gutiérrez, in your Afterword for La Grande, representing another, if slightly less sinister, facet of that same binary, as they take their impossible stroll at the beginning of that novel.

I’m not sure what I can add about character. It’s an incredibly difficult question, and one that I’ve thought about mostly as a translator. I’ve spent a good deal of energy trying to distinguish the various narrative voices in the books, the shifts in register or tone that suggest that a different person is speaking, or that indicate that the narrator has assumed the voice of one of the characters. What was clear from the first pages of Glosa was that storytelling was an obsession for Saer, that character was not given, but that it took shape around different kinds of narrative. As you’ve mentioned, he took liberties in “revising” or refashioning his characters across the novels, which suggests that he didn’t consider them preexisting or even stable entities, or surrogates, to which he then had to demonstrate some kind of fidelity. He may have been more interested in their function within the narrative, what kind of space they took up. And so part of the nature of the Tomatis character, his charm, is the kind of storytelling he embodies. I hope someone translates Lo imborrable so that you can see his voice in full force.

Saer also seemed fond of weird juxtapositions and doubles (now I’m just riffing): so we get, for example, the Garay twins, the two “versions” of Saer in Nula and Gutierrez, and the longer version of this in Scars, with Ángel and his double. It’s possible that he thought of the Garay twins less as two distinct “people” in his narrative universe, than as two different ways that a character might develop. Probably owing to an unhealthy interest in Bergson, which he (and everybody else) picked up from Borges, he decided to make those two different possibilities simultaneous. Whereas many novelists explore character primarily through the lens of familial relations and sedimentation—Faulkner, a great influence on Saer, comes immediately to mind—Saer seemed more interested in how affinity and friendship generate personality types, and how these relations radiate outward in space, horizontally rather than vertically, from one generation to the next.

Since we’ve been naming Saer’s characters willy-nilly, maybe we might pause here to set down a dramatis personae—a sort of “Who’s Who in La Zona” for readers coming to Saer’s world for the first time, since they pop up again and again?

I’m sure to leave someone out, which will be embarrassing. But I think I can safely talk about five men as a core group. Most if not everyone else who appears as a significant character is in some way connected to these people, either in friendship, in love, or in family. First and foremost is of course Carlos Tomatis, a journalist for the regional daily, La región. He is also a novelist and a screenwriter, and his connections in the literary world (for a time he edited the paper’s literary supplement) give him entree to the Buenos Aires literary scene. He was married and divorced.

Tomatis’s best friend in childhood was Horacio Barco (his daughter, Gabriela is, in my opinion, the most important character in La grande, in that she represents a kind of renewal). Barco is the personification of much of the philosophical positioning in Saer’s books. From his mouth issue many of the metaphysical gems in the novels; he seems to be the only true skeptic.

Intimately connected to that pair is a trio of guys who went to law school together: César Rey, Marcos Rosemberg, and Sergio Escalante. César and Marcos were best friends for many years. At some point, César had an affair with Marcos’s wife, Clara, which lasted a good while. It was only after César died that Clara returned to her husband. Marcos eventually became a politician. Sergio Escalante is perhaps the most nihilistic character in the history of Argentine letters. He is the “gambler” character from Scars. After he loses everything, he marries his fourteen-year-old maid, moves to the outskirts, and lives off of what he can scrape together.

I’m curious also whether you have a sense of how Saer’s poetics changed over his career, or whether his concerns, as we’ve discussed them, emerged fully formed? In English, from Serpent’s Tail, we’ve had Nadie nada nunca / Nothing Nobody Never (1980), El entenado / The Witness (1983), La ocasión / The Event (1987), and La pesquisa / The Investigation (1994)—and not in that order! From Open Letter, in your translations, we’ve first gone back to 1985 for Glosa / The Sixty-Five Years of Washington, then back farther still to 1965 for Cicatrices / Scars, and then all the way forward to 2005 for La Grande. Yet, while there are certain changes in the styles between these titles, there’s a strange non-temporality in them, as seems only appropriate… obviously, the extremity of the style in Nothing, for example, where every moment is stretched to near endlessness, is very different from the superficially simpler style adopted for much of Scars, but then it is a close kissing cousin to virtually every other title on this list.

It’s seemed to me that there’s a far greater gap between the “historical” novels we’ve gotten in English (The Witness and The Event, with The Witness still his best-known title, I’d say) and the ones set more or less in the present day, than there is, say, between the voices/concerns of Washington and La Grande, despite the (real and fictional) time passing between them.

And this leads me too to the question: barring the answer “all of them,” for the moment, which other of Saer’s titles do you think are most needful in English?

Scars is a great book for the uninitiated, because it already contains much of the poetics that come later, albeit in germinal form. In Scars, Saer treats a single event—the murder of Fiore’s wife—from multiple perspectives. In this early book, the perspectives are divided up into sections, so that the reporter, the lawyer or gambler, the judge, and the murderer each speak separately. In later books, these perspectives tend to mingle, and, as I’ve said, the distinction between narrator and character tends to dissolve. In Scars, Saer is more obviously playing with or against his influences. Dostoevsky, Chandler, and Faulkner are either mentioned outright or the references are so obvious that they may as well be.

In later books, these intertextual glances either tend to disappear or become increasingly veiled. I can’t tell which. By the time you get to La Grande, the influences take a postmodern turn: Nula’s character, for example, seems to be a strange brew of Diogenes, Deleuze, and Don Juan. In Scars, particularly in the section narrated by the judge, you already see the expansion at work in the formal style, that weird origami syntax combined with a near cosmic slowness that is almost unbearable in Nobody Nothing Never.

I may be wrong, but I think it’s in the early ’80s that Saer begins to write about narration. Not coincidentally, it’s in the late ’70s and early ’80s that the already bad situation in Argentina gets very bad. So in a sense, yes, Saer was always interested in what you brilliantly call equivocality, but the execution changed, especially after Nobody Nothing Never, which really marked a turning point.

I had never considered a division between the contemporary and historical novels, but I think it’s a good one. Although I think it would be useful to set The Witness apart from the other two historical novels, The Event and Las nubes. On the other hand, all of the historical novels are similar to Scars in that they occupy a specific genre and undermine its authority. In The Witness, this attack—on the truth value of the testimony, or “eye-witness account,” in this case—is particularly intense. I’m afraid this is all rather vague. It’s hard for me to say much of substance on the historical novels because I haven’t translated any. Incidentally, if I were to translate another book by Saer, I would want it to be Las nubes. One of my Saer informants laughed when I told him this. He thinks El limonero real is the best Saer novel yet to be translated, and he may be right, but I’m thinking of it more from the translator’s perspective, the challenge of the research involved, and so on…

It’s probably obvious by now, but I would say that El limonero real (the first fully formed “Saerian” novel) and Las nubes (the third historical novel) are important to have in English. I’d also like to see someone publish Lo imborrable, for the voice of Tomatis, and El río sin orillas, his book about Buenos Aires.

Speaking of El río sin orillas… I’m curious, given that virtually all the heavy-hitters of Argentine literature translated into English are Porteños by birth or choice, what did the capital mean to Saer, and to what extent is he rewriting the dominant literary culture of his country by more or less excluding it from his fiction? (Certainly, none of the translated fiction to date does much more than mention Buenos Aires as a stopover on the way into or out of the country, if memory serves.) Who, I wonder, did Saer consider his peers within Argentina? (And then, I might as well ask, beyond its borders?)

I know less than I should about Saer’s relationship to Buenos Aires, either as a real place or as a literary landscape. You are right that in his fiction Buenos Aires serves mostly as a stopover, a transition place. With some exceptions. We know, for example, that César Rey, an important character in the Saer universe, lived in Buenos Aires for a time, and died there when he was hit by a subway train. But to my knowledge that experience is only ever narrated second-hand. And of course Nula’s father, after he joined the guerrillas, was killed in Buenos Aires. One of the greatest moments in anything I’ve read by Saer comes when he describes the outskirts of Buenos Aires, the vast, anonymous expanse into which Nula’s father was lost, and from which Nula’s grandfather recovered the body of his lost son.

There are many, many more examples. These are just the ones I have most readily at hand in my memory. So Buenos Aires was certainly not nothing to Saer. But it does seem, from these examples at least, that it was a place into which one disappeared, willingly or not, whereas la zona was a place where one was recognized, and which reflected that recognition in its landscape, if that makes any sense. El río sin orillas is the kind of book that, in a sense, is particular to Argentine literature, and in another sense is universal to all literatures. In a sense, El río is Saer writing himself into a long Argentine tradition of inscribing Buenos Aires. At the same time, many great writers have taken on “the novel of the city” in various ways. In this sense, I think Paul Auster is one of Saer’s peers, inscribing a particular historical moment in New York. And though their writing is very different, I think of Günter Grass’s Danzig, too. Within Argentina, the work of Sergio Chejfec shares a lot with Saer’s, although, curiously, Chejfec disagrees with the comparison. I’d be curious to hear why.

***

Jeremy M. Davies is Senior Editor at Dalkey Archive Press. His first novel, Rose Alley, was published in 2009; his second, Fancy, will be published by Ellipsis Press in November 2014.