In the science fiction of movies and television, the future looks more or less uniform. Digital technology is (somehow) even more omnipresent than it is today. A continuous mosaic of audio and video spills across every available surface. A glass skyline stretches toward the horizon with sleek automobiles gliding past the frame. If human culture has existed, say, for more than a few decades, the evidence of that is not visible.

This kind of scenario is a reflection of contemporary reality, of course. Science fiction has traditionally dressed up the future in contemporary styles. And this presentism seems justified today. In our swiftly urbanizing world, the built environment often appears as if it had emerged overnight, without precedent. The megalopolises of Asia and Latin America, with their endless high-rise apartment blocks and elevated thoroughfares, seem to presage something universal for humankind, at least while we can keep industrial civilization going.

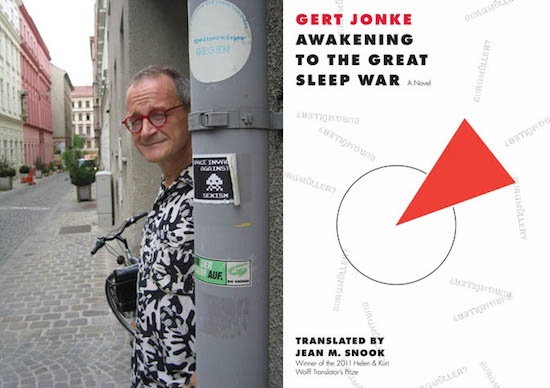

But there is another kind of future city, one defined by the accretion of time, where reality is defined by the weight of history rather than its absence. The late Austrian polymath Gert Jonke made a career evoking such places. His complex, often bizarre novels explore how the past continually impinges on the present, particularly in Awakening to the Great Sleep War, first published in 1982 and brought to English last year by Dalkey Archive Press.

The book follows the adventures of a young man named Bergmüller, an “acoustic-interior designer,” searching for love in a vast and fantastical city, unnamed but unmistakably modeled after Vienna, with its Baroque architecture, its winding backstreets, and its hyperarticulate caste of critics, musicians, and philosophers roving about like ants in the shadow of an immense and troubling cultural legacy.

In Jonke’s fictional world, human beings have left centerstage. They drift about, often indistinguishable from their fictional backdrop. Bergmüller himself is a rather flat protagonist. He spends his time flitting between lovers and playing the contemporary flâneur. But exactly how this succession of bodies and buildings affects him remains unclear.

The city itself forms the dominant personality within the novel, evidenced by the unforgettable opening passage, which literally describes the metropolis coming to life at the break of day.

In the morning, the walls blow their noses, hanging their bleary eyed bedding out of the windows, the roof trusses cough through asthmatic chimneys and some buildings sneeze through their opened skylights; now and then an entryway shoves its stairwell bursting with stairs out onto the street, and sometimes entire suites of rooms are pushed through their walls into public places, while the cellars press down on their heaps of potatoes, preventing them from rising up in rebellion when the countless coal sacks, filled to bursting, blow gobs of smoke into the public transportation system through the bars on the windows.

Among the various examples of living architecture are the caryatids, female statues serving as architectural support. Bergmüller unwittingly sets off the eponymous war by teaching the caryatids and their male companions, the telamones, how to sleep, an event with dire consequences. “Nothing even remotely like falling asleep had been included in the blueprints; even the faintest hint of telemonic tiredness would bring the buildings of half the city to cave right in, a single dream would bring catastrophe, desolation, mountains of rubble…”

These conjectural scenes bring to mind the destruction in Vienna during the Second World War, an event not altogether unconnected with the city’s famed high culture. Along the southern wall of the Austrian Parliament stands a line of caryatids facing out toward the Volkstheater. It was here that a young Adolf Hitler was rumored to have helped paint frescos as an aspiring artist. There’s no proof that this ever happened, of course, but the story has entered Viennese legend. Pull back the curtain of civilizational achievement and you might find catastrophe lurking.

The characters in Jonke’s novel have their own confrontations with history. Among Bergmüller’s loves is an unnamed writer of intense character. She spends her time at work on a book called Portrayal of the World, her magnum opus to be. Their relationship is fraught. She refuses all intimacy with Bergmüller until she has thoroughly exhausted him with her anecdotes, philosophical ponderings, and paranoid theories, which all take up a considerable portion of the novel. Her rough treatment of him forms a small part of what Bergmüller calls the narrative war, a battle to determine the very nature of representation, one that spans centuries and will not be decided until the writer has fashioned a completely new reality from scratch.

Chief among the belligerents in this narrative war is Herr Karl, a godlike figure, possibly the historical Charlemagne, who has persisted into the present day as some kind of semi-immortal being held in a limbo-like state between life and death. The love interest/writer’s fixation on Herr Karl arouses jealousy within Bergmüller. Tired of her constant philosophic battles and the strange phenomena that accompany them, Bergmüller suggests that “real landscapes, cities, you’ll feel everything yourself, we’ll both experience it, we’ll both be able to experience ourselves at last…” In this moment, uncharacteristically direct for this heady novel, Bergmüller speaks for everyone who’s ever exhausted by the life of the mind.

A single question pervades the whole novel: How can one keep a level head under the influence of so much culture? Jonke does not put forth any obvious answers. A path seems to lie between Bergmüller’s passivity and the writer’s obsessive iconoclasm, between serving as an inert vessel for past culture and remaking the world from scratch.

The world gets older, at least in parts. Archives fill with documents, museums with artifacts, concert halls with music. In his densely constructed fictional worlds, Jonke shows the beauties and troubles of cultural abundance. As dilemmas go, it’s all rather high-toned. But debates over history and representation have been going on as long as civilization itself, all too often providing a veneer of culture for acts of gross violence and exploitation. The eponymous Sleep War of Jonke’s novel might be a work of metaphorical fancy, but it serves as a caution. Not everything contained in art should be brought to life.

As time advances, memory accumulates. We experience more of the past, both as individuals and as members of human society. Perhaps one day, through some feat of technical intelligence, our built environment will actually achieve some degree of sentience. Awakening to the Great Sleep War, then, might well serve as a guide when a phrase like “the city remembers” becomes more than merely figurative.

*****

Matthew Spencer is a writer, born and raised in western Colorado, who lives in Seattle, Washington. He worked as an English-language teaching assistant for the 2013-14 academic year in the town of Bad Ischl, Upper Austria. He blogs about art, music, history, and literature at Unpaginated.