When New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio visits Grassano, the birthplace of his grandmother Anna Briganti, he’ll be walking in the footsteps of not only his forebears but also an Italian author whose first book was a cornerstone of one of New York’s best-known publishing houses. The coincidence is more than a geographic one: the reforming mayor will be returning to a family hometown, but also to a place that led to a masterpiece of social reporting and reformist philosophy.

Carlo Levi’s book, Christ Stopped at Eboli (Cristo si è fermato a Eboli), published in 1945, was one of Roger Straus’s first acquisitions: it was “a harbinger of things to come,” according to Hothouse, a history of the publishing house FSG, “a critical triumph and best-seller in 1947.”

The book was written by Levi, a Turin-born Jewish doctor and painter, who recounts a year of his internal exile in Grassano and a neighboring village, Aliano (called Gagliano in the book), for anti-Fascist activism.

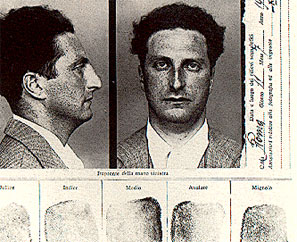

Carlo Levi mugshot at the time of his internal exile in Grassano

Carlo Levi mugshot at the time of his internal exile in Grassano

Although de Blasio’s grandmother left Grassano decades before Levi lived there in the mid-1930s, the town was still much the same place it had been. Ironically, it was a place with close ties to only one city in the world, according to Levi, and that city was not even in Italy. “Yes, New York, rather than Rome or Naples, would be the real capital of the peasants of Lucania, if these men without a country could have a capital at all.” Life in the ancient Southern Italian region of Lucania, according to Levi,

was entirely American in regard to mechanical equipment as well as weights and measure, for the peasants spoke of pounds and inches rather than of kilograms and centimeters. The women wove on ancient looms, but they cut their thread with shiny scissors from Pittsburgh; the barber’s razor was the best I ever saw anywhere in Italy, and the blue steel blades of the peasants’ axes were American.

And when Carlo Levi’s sister, like him a physician, came south from Turin to visit, there was a clear division between the americani, or peasants who had emigrated and returned, and the more prosperous and better educated “gentlemen” of the village. The gentlemen were astonished that a woman should be a doctor; the peasants who had lived in America were perfectly matter-of-fact about it, and cared only about arranging for her to examine some ailing grandparent or child.

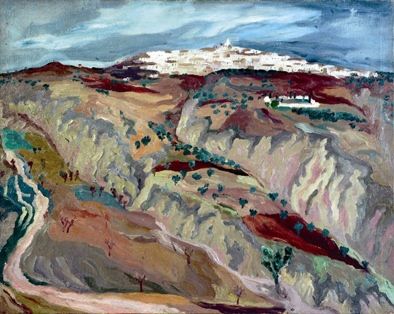

Painting of Grassano by Carlo Levi

Painting of Grassano by Carlo Levi

De Blasio will also be walking in the footsteps of long-ago Mayor Vincent Impellitteri, who visited his hometown of Isnello, Sicily, in September 1951. Interestingly, Carlo Levi was there for that event as well.

There was something mysterious about this Impellitteri they were all waiting for, whom no one knew, because he had been taken away when he was just a one-year-old baby, fifty years earlier, and he was now returning, bathed in a halo of glory like a saint descending from heaven, from America: and, even though no one there had ever met him, he was still one of them.

Levi enjoys himself with Impellitteri’s visit, and lightly lampoons the Christological aspects of a visit to a small village by the mayor of New York. He pointed out that Isnello is well known for a venerable folk passion play called La Casazza staged during Holy Week, with peasants garbed as Jesus, St. Joseph, Herod, and Pontius Pilate. “Today, too, they were all actors, but there was a real main character: after the Flight into Egypt that took place fifty years ago, this was the entry of Christ into Jerusalem.” But Signor Impellitteri certainly didn’t ride on a donkey; he emerged waving from a handsome gray Pontiac “to the din of clapping and cheering and the town band.” And once he had moved on, “the boys of the town immediately crowded around the car, pushing, shoving, and elbowing their way forward to touch it.” Levi quotes the boys, “egging one another on, with serious faces, as if they were performing an act of grave importance: ‘Let’s touch the car, so we can leave for America.’” Levi notes that the car, which had only just arrived, “had already become a relic.”

During his exile, Levi used his medical training to care for the Lucanian peasants, and he describes the conditions in which he worked. In the single-room peasant houses, animals slept under the bed, while infants dangled from the ceiling in cradles swinging on ropes. “The room was divided into three layers: animals on the floor, people in the bed, and infants in the air. When I bent over a bed to listen to a patient’s heart, […] my head touched the hanging cradles, while frightened pigs and chickens darted between my legs.” But what struck Levi most of all, in the many houses he had visited, and he’d been in nearly all of them,

were the eyes of the two inseparable guardian angels […] the black, scowling face, with its large inhuman eyes, of the Madonna of Viggiano; on the other a colored print of the sparkling eyes, behind gleaming glasses, and the hearty grin of President Roosevelt. I never saw other pictures or images than these: not the King nor the Duce, nor even Garibaldi; no famous Italian of any kind.

Sometimes a third item formed a trinity: a dollar bill, “like the Holy Ghost or an ambassador from heaven to the world of the dead.”

Of course, almost eighty years have passed since Levi lived in Mayor de Blasio’s grandmother’s hometown, nearly sixty-five since Mayor Impellitteri visited Isnello. But Levi’s eyewitness account describes a place that is probably close to the Grassano that Anna Briganti left in 1902. And this part of Italy—a part of Italy that as the book’s title suggests, was beyond where even Jesus ventured—remains poor and underdeveloped. It’s a place that has long looked to New York City—more so in the years before World War II, when “America receded ever more into the distance, lost in the mists of the Atlantic like an island in the sky.” That has always been their beacon of hope, not, as Carlo Levi notes, their theoretical capital, Rome. “From Rome came nothing,” he wrote. “Nothing had ever come but the tax collector and speeches over the radio.”

***

Antony Shugaar, Asymptote Italy editor-at-large, is the author of Coast to Coast and the coauthor of Latitude Zero: Tales of the Equator. He is a translator: among his most recent titles are The Crocodile by Maurizio de Giovanni, Resistance is Futile by Walter Siti, Other People’s Trades, and If Not Now, When? by Primo Levi. He is working on a book about translation for the University of Virginia Press.

***

Image via Fondazione Amendola