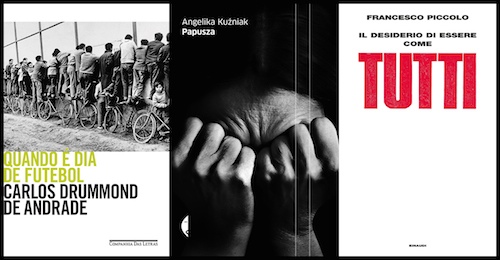

Antony Shugaar (editor-at-large, Italy): I’m reading the shortlisted books for Italy’s top literary prize, the Strega (named after a saffron-yellow after-dinner liqueur), which were announced in early July. One of the most interesting is Il desiderio di essere come tutti, The Desire to Be Like Everyone Else (Einaudi) by Francesco Piccolo, which amounts to a psychic autobiography of the past 40 years of Italian life, and the transition from a time of communist ideals to the present. Suffice it to say that the book is broken down into two parts: 1) The Pure Life: [Italian Communist Party leader Enrico] Berlinguer and Me and 2) The Impure Life: Berlusconi and Me. And I’m pleased to say, it was the winner.

Another notable title in the shortlist is La vita in tempo di pace, Life in Peacetime (Ponte alle Grazie) by Francesco Pecoraro. A massive novel, the first by an author turning 70 this year, it happens to be the story of the last day in the life of an engineer named Ivo Brandani, born in 1945 (he too is 70, coincidentally the same age as both the author and the Italian republic, risen from the ashes of Mussolini’s Fascism). This book tells the story of a nation and a human being, through a quasi-biological viewfinder, as if our busy little activities were the pursuits of bacteria and bacilli. Comparisons have been made to Robert Musil; one thinks also of Hermann Broch’s The Death of Virgil.

Two other books in the shortlist are Il padre infedele, The Unfaithful Father (Bompiani) by Antonio Scurati, which tells the story of a successful chef and new father in a suddenly collapsing marriage, an observation of the mores and stylistic details of modern Italy, where stardom comes with a white toque, and fatherhood comes with a poorly translated and completely outdated instruction manual. Then comes Lisario o il piacere infinito delle donne, Lisario, or the Infinite Pleasure of Women (Mondadori) by Antonella Cilento. In this picaresque tale set in seventeenth-century Naples, a young sleeping beauty—literate and lovely—is awakened from a coma by a mountebank with probing fingers.

Eric M. B. Becker (assistant managing editor): Finally, my determination to make good use of my summer has borne fruit. After successive summers with good intentions, my to-read pile is being devoured faster than ever (I say as if to tempt fate).

We are in the year of a World Cup, and a World Cup in the football (soccer) country, so what better place to start than 20th-century Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s Quando é dia de futebol, a collection of his poems and crônicas written for newspapers on the topic of futebol? What’s most exciting about this collection is that it’s not really about football at all, but rather explores the sport’s relation to Brazilian identity and extols the real benefits of competition: learning to rebuild following failure and the importance of community.

Lest you think the collection is nothing more than an ode to the players on the pitch, Drummond also considers the manipulation of football for private and political gain (see? There’s something for the curmudgeons, too). While the collection is not available in English, you can get a taste for the work with this piece I published over at MobyLives last week. So if your national squad is headed home or something else has got you down, take away this piece of Drummondian wisdom: “Losing,” he tells us, “implies the shedding of dead weight: a new beginning.”

Florian Duijsens (senior editor): After a long period of work in which the main sources of distraction were my morning runs through Volkspark Friedrichshain and marathon viewings of RuPaul’s Drag Race, my June was a little more book friendly: I started off with two wonderful ebook originals, one by Karen Russell (Sleep Donation, read out loud in the app by the goddess of all that is New York, gawky, and elegant, Greta Gerwig) and one by Gideon Lewis-Kraus, No Exit: Struggling to Survive a Modern Gold Rush. The latter is an indispensable read both for those at a loss to understand the continued existence of the “startup scene” and for those who enjoyed the first season of HBO’s Silicon Valley but were previously unfamiliar with terms such as “runway” or “first-round funding.” My German book club, meanwhile, finished reading our first full Christa Wolf book (most of us failed to make much headway into Kassandra), a challenging novella called Unter den Linden (available in English in What Remains and Other Stories, translated by Rick Takvorian). Though the story’s lightly hallucinatory dream logic (and my basic German) often made it hard to know just what was happening to whom when, Wolf’s book captivated me from its very first paragraph:

I have always liked walking along Unter den Linden. And most of all, as you well know, alone. After I had avoided it for a long time, the street recently appeared to me in a dream. Now I can finally tell of it.

I also enjoyed several shorter English-language novels while on the road through Germany, Switzerland, and Austria: Evie Wyld’s dark novel of guilt, All the Birds, Singing; Penelope Fitzgerald’s cruelly comic The Bookshop; Evan S. Connell’s The Connoisseur (on the fatalist helplessness faced by those who find themselves having become collectors); and the great Shirley Jackson’s impossibly funny tale of apocalypse and inheritance, The Sundial, blessedly and finally reissued as a Penguin Classic. Next up, in preparation for a month spent on a cargo ship, is Geoff Dyer’s Another Great Day at Sea: Life Aboard the USS George H.W. Bush.

Julia Sherwood (editor-at-large, Slovakia): I’m afraid I’ll be rather gushing in what I say about Papusza, a wonderful story of a remarkable woman, beautifully and sensitively told.

Drawing on recorded interviews with the Romani poet Bronisława Wajs (1908-1987), known as Papusza (Romani for doll), as well as recollections of her friends, relatives, and supporters, Angelika Kuźniak’s Polish account makes Papusza’s voice sound authentic, retaining just the right amount of spelling mistakes and stylistic quirks of this audodidact (without overdoing the folksiness). Remaining largely invisible, the author tells Papusza’s tragic story with great empathy, from her subject’s perspective, letting her complicated personality come to the fore.

Although Papusza is a slim book (just over 186 pages, including many evocative photographs), the author’s descriptions of the key relationships in Papusza’s life are far from one-dimensional, and her portrait of the Roma community is vivid. This should be compulsory reading today, with xenophobia and anti-Roma prejudice on the rise. Yet Kuźniak depicts the Romani way of life without romanticizing it, showing its macho culture and forced marriages and the fierce tribal codes that Papusza dared to transgress.

The final chapters, which describe how the Roma community expelled Papusza, suspecting she had given away their secret customs and codes, her subsequent isolation and nervous breakdowns and the awful conditions in which she lived, are deeply moving. I finished this extraordinary book with a huge lump in my throat (and can’t wait to see the film).