Read all previous posts in Asymptote’s “Mimes” translation project here.

Two talented translators took on today’s portion of Marcel Schwob’s Mimes, with different-yet-stunning results that together call attention to the transformative power of translation. Jean Morris begins with her translations, commentary, and illustrations, followed by Virginia McLure’s more modern take on Schwob.

Mime VI. The Garlanded Jar

The jar is honey-coloured earthenware, its base thrown by the skilled hands of a potter, but I smoothed its rounded belly into shape myself and filled it with fruit as an offering to the garden god. Alas, though, the god’s attention is elsewhere: fixated on the quivering foliage, in fear that robbers might breach these high garden walls. In the night, dormice rooted stealthily among my apples and gnawed them to the pips. Here these shy creatures were, at four in the morning, waving their downy black-and-white tails. And here, at dawn, came Aphrodite’s doves to perch on the violet-stained rim of my clay pot, fluffing up their tiny, flickering neck feathers. As I watched here, beneath the trembling noon light, a young girl alone stepped forward to the god with crowns of hyacinths. She saw me, of course, crouched behind a beech tree, but paid me no heed as she laid her garlands on the jar, now emptied of its fruit. What do I care if the plucking of his flowers displeases the god, if the dormice gnaw my apples and the doves of Aphrodite bow their tender heads to one another? Drunk on the heady scent of freshly gathered hyacinths, I twined some in my hair, and here I shall wait until tomorrow for my girl who comes at noon, my garlander of jars.

Mime VII. The Disguised Slave

Come now, Mania, my crazy goddess, won’t you chastise this insolent lad? Lash him with a fine whip of Anatolian leather! I bought him from Phoenician merchants for ten minae, and he has not gone hungry in my house. Ask him if the cooks gave him only olives and salt fish. No, he has filled his belly with stuffed and roasted pig stomachs, eels from Lake Kopaida, and fatty cheeses still bearing the imprint of their wicker molds. He has drunk the unblended wine I was saving in fragrant goatskin flasks. He has emptied my flagons of Syrian balm and his tunic is dyed purple—no laundress dipped him in a wine vat! His tresses stream behind him like the flames of a burning torch: the barber has not been near these with his scissors. Every day, my women pluck his body hair while the lamplight’s rosy tongue licks across his skin. His loins are whiter than my throat, whiter even than the rumps of those ivory lions carved on the handles of my best knives.

And now, I swear he has drunk as much wine from my vaults in one evening as Demeter’s initiates consume in their three days of revelry at the Thesmophoria. I thought to find him snoring, lying on the ground near the kitchens, and as punishment to have the men who grind my spices pound his lips raw with a pestle—let him expiate his drunkenness in the acrid smell of freshly crushed garlic! But I found him here, staggering, wild-eyed, clutching my polished silver mirror. Our thrice-guilty youth had been to my jewelry case and stolen one of my gold cicadas to decorate his coiled hair. Then, standing on one leg, his body swaying, trembling from the wine, he wrapped his thigh in some gauzy cloth. This, too, I recognized: it was my own loincloth, the one I like to wear beneath my tunic when my lady friends and I are off to the feast of Adonis!

*

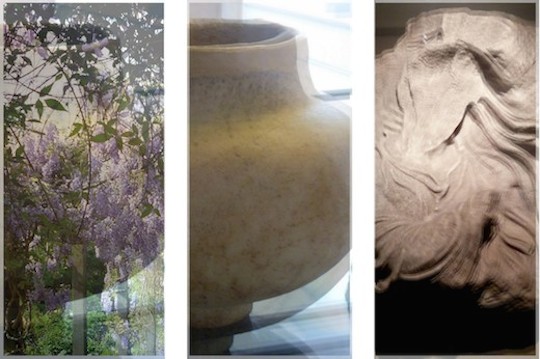

Jean Morris: Fresh from gorging on boxed sets of Game of Thrones, I found the Mimes instantly set themselves in some cod-classical/Mediterranean CG city of that fantasy world, with its saturated colors and dark figures silhouetted against glowing light. Not so inappropriate—think time and distance, layers of creation and re-creation. Thence the somewhat emphatic and exclamatory tone, opting to “push” the translation just a bit, saturate the colours of the words. This sometimes meant using more words, being more explicit. Perhaps the most egregious push was in Mime VI: “drunk on the heady scent” is nowhere in the original, but as soon as I thought of hyacinths their smell pervaded everything! And some slight changes or expansions in Mime VII: who is Man[n]ia? where is Paphlagonia? (it’s in Anatolia), and what does an ancient Greek wear under his tunic? Is this “dumbing down,” or a justified nod to our loss of the easy familiarity with classical tropes that Marcel Schwob would have taken for granted? The illustrations—I took the photos mostly in the Greek galleries at the British Museum—are also intended as a little “push,” adding some texture and immediacy.

***

Gesture VI. The Wreathed Jar

A potter having turned the base of a jar I molded and curved from golden clay, I heaped it with fruit for the gnome who rules the garden.

But he studies the shuddering leaves, terrified thieves will pierce the walls. By night, the stealthy dormice have sunk their muzzles among the apples and champed them to pips. At the fourth hour, they shyly twitched their downy white-and-black tails back over the glazed edge. Daybreak, and lovebirds perched on my jar’s violet rim, bristling their little feathered ruffs. Subject to the simmering noon, a young girl stepped alone toward the gnome carrying wreaths of hyacinth. I know she noticed my shadow, sloped into a beech’s crook. But without a glance at me, she garlanded the jar-with-no-more-fruit. What do I care if the gnome resents his plucked flowers, what do I care that the dormice bit up my Galas, that the lovebirds twist their tender necks to one another as if to ask—!

I have braided my hair with cool hyacinth, and until noon tomorrow I will watch the trees for the she-crowner of jars.

Gesture VII. The Slave in Costume

Hey, Mannia—come break one off on this cheekster with a strong lash of this leather hailing from conquered shores.

I bought him for ten big ones from the Lebanese merchants, and I’ll be damned if he’s suffered any hunger in my house. Let him tell what the cooks have given him: olives and salted fish. He’s glutted himself with stuffed and roasted belly, eels from that famed lake, fatty cheeses still gridded from their wicker molds. He has drunk the unmixed wine I had stashed in fragrant goatskins. He has emptied my phials of expensive balm, and dyed his tunic purple-violet: no servants have dunked him in the baths. His mane glints like the crests of a gold torch; the barber’s scissors have kept their distance. Every day my women pluck his hair, and the lamp’s blush tongue laps at his skin. His hips are whiter than my bosom or the ivory hindquarters of lions carved onto knife handles. I’m not kidding, he drank as much wine from my cellar in one night as fertility rite revelers do in three whole days. Once, I thought I saw him sawing logs, sprawled out in front of the kitchen, and I would have brought down the thugs to scrape his lips—to discipline him!—with a mortar-pestle; he would have paid for his drunkenness with the acrid taste of freshly crushed garlic.

But I found him shivering, eyes out of focus, gripping my polished silver hand mirror, and—three times over impure, this one—having lifted from my jewelry case one of my gold pieces, he had plunked it over his kinky curls. Then, balanced on one leg, his body quivering with wine-shakes, he bound his thigh with a length of gauze that I, as a habit, sheath myself with when I venture out with friends to see the statues laid out in the streets, the parades crying or cheering.

*

Virginia McLure: What I most struggled with in both of these translations was how the text could be translated in a style of mythological grandeur or, on the other hand, of tangible simplicity. With its luxurious but spare details—the garden deity, the young woman acting almost as an apparition, the greenery and fruit—Mime VI appears classically (as in, Roman and Greek) sensualist in a way that I wanted to convey without using those references as a coy nudge to “the learned.” Regardless of Marcel Schwob’s intentions, whatever they might have been, I feel that the text itself wants to be “modern” in the way that Baudelaire’s prose poems are, by which I mean, written in language that both mimics reality (raw, common sensations) and projects the unfamiliar (strange images or combinations). To that end, I chose to interpret the “god of gardens” as a “garden gnome” and “the birds of Aphrodite” as “lovebirds” to ground the scene—ripe with allegory and allusion—in an actual garden with dirt and mice and a not-quite flirtation. I also chose uncommon translations of certain words (“sous” became “subject to” rather than “under” or “beneath”; “la couronneuse” became “she-crowner”) as moments of surprise within the regular scene.

With MIME VII, I sought to replace all the ancient allusions (Paphlagonia, Phoenicia, Lake Copaïs, the festivals of Thesmorphia and Adonis) with tangible objects or places. In part because classical references annoy me when they imply an author’s saying, “Oh, yes, I’m part of the classically educated, and if you get my references, you may be too!” And in another part because, in following my before-mentioned personal definition of “modern” prose poetry, I wanted the nuances implied by the classical references to be immediately accessible. So Paphlagonia, long under Roman rule, became “conquered shores,” the Phoenicians became “Lebanese” (Phoenicia covered some of modern-day Lebanon and Syria), and for both the rites of Thesmorphia and Adonis, I used what my research had turned up as the actual events of those festivals rather than simply naming them. Both were more than one day, and had more than one type of activity associated with them. One detail that especially stood out to me, in researching the festivals of Adonis, was that on one of the days, revelers would lay down statues of Adonis in the street as if they were corpses, lamenting them to lament Adonis’ descent into the Underworld, away from his lover Aphrodite. Because it is moments like this that make me love translation so much—like mini history lessons, minus all the boring filler of dates and battles—I wanted to feature those details over honoring the proper names or places of those ancient allusions.

***

Jean Morris lives in London and came late to the pleasures of literary translation after using her language skills in the global reaches of politics and higher education.

Virginia McLure edits La Fovea, and has worked with A Public Space, BOMB, LSU Press, and The Southern Review. She has writing featured or forthcoming in Bedford + Bowery, BOMB, The Nashville Review, and Meridian.