Gonçalo M. Tavares’s A Man: Klaus Klump may be the final installment of the author’s “Kingdom” cycle to be translated into English, but newcomers to Tavares’s work (I’m among them) shouldn’t shy away: Klaus Klump was the first work Tavares published in the series. And even better for us newcomers, intrigued by the author’s “Brief Notes on Science” that appeared in Asymptote’s April issue, is the fact that Klaus Klump works on the same aphoristic, probing level as his “Notes.”

Except this time there are characters. Or something resembling them.

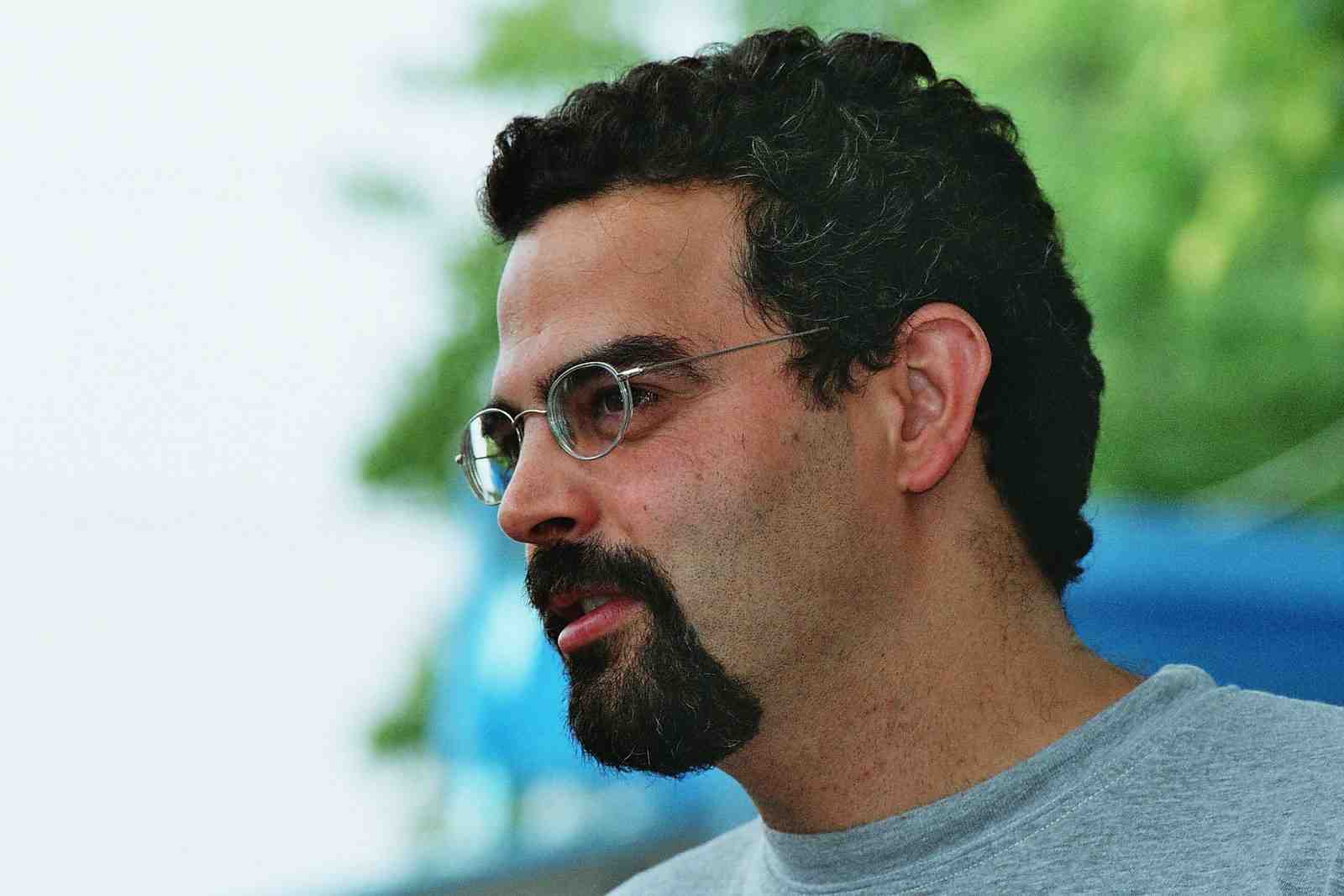

The author, Gonçalo Tavares, is a Portuguese writer born in 1970 whose work Jerusalem (the third in the “Kingdom” cycle) won the 2005 José Saramago Prize, awarded for a Portuguese-language literary work written by a young author. But before Jerusalem, there was Klaus Klump, with a book blurb that reports it as “a harrowing portrait of a man without values, making his way through a world almost as immoral,” which is about as vague as it gets. Actually, the novel’s unmentioned plot is fascinating, especially in today’s doorstop-book-saturated literary landscape.

In under a hundred pages, the work describes an unnamed country (whose inhabitants bear the distinctly un-Portuguese names of Klaus, Johana, and Herthe) as it descends into horrific war, then casually recovers. The war’s toll on this strange, Germanic society is described in spare, pleasantly ambiguous detail, with its focus on the enigmatic figure of Klaus Klump.

What does he look like? “Klaus is a tall man”—end of description. He is also a publisher of controversial, quasi-rebellious books, but, more crucially for his character, Klump is an heir to his family’s substantial fortune, and lives a life of complacency even as the war breaks out. Soon, though, the war transforms Klump into a beast, and at the end of the war, his character changes once again.

With Klump, Tavares examines the sad turmoil of an increasingly militarized, mechanized society. In his descriptions of this society, Tavares blurs the lines between humans, the organic world, and the mechanical-military world for a reading experience that’s deeply disturbing (in all the right ways).

Take these descriptions of the unnamed society at war. “An enormous tank is a masterpiece next to water,” Tavares writes. “How simple water is, how insignificant, next to powerful technology.” Or later, “Children are treated well. Just like the infrastructure of the buildings in the city center. That which is useful is treated well.”

The values of the human, the organic, and the mechanized-militarized have become so intertwined that they are all judged by the same perverse standards: an object’s complexity, its usefulness; an organic thing’s complexity, its usefulness; a person’s complexity, its usefulness. And this is perhaps where the horror of Tavares’s unnamed society at war comes from—the takeover of its pathological mechanization, described in the novel as “the end of History.”

Early in the war, Klump encounters a long-imprisoned madman proclaiming, “For me, History has ended. If they lock me up in a room for years, where is the country? No country ever came here to save me, I spit on the country.” For this so-called madman, history exists only as long as there is a relationship between him and his changing-in-time society, and in prison, none does; none can. Later, Klump awakens from his misanthropic daze to a similar thought: “But what was the sound that emanated from machines, if it was neither the deformed sound of nature, nor a sentence? […] Klaus’s head was now fascinated by the sound, the nearly stupid, nearly History-less sound of bullets and bombs. The sound that proclaimed a new God.” Bullets and bombs during war, prisons during peace: these both signal the same end. The end of a history of human beings, of societies and living organisms and natural things that change with time.

So what does the start of one war, the end of it, the start of another, the end of that one, in this country or that, in this language or that, mean when history has ended? When the sound that a bullet or a bomb makes stands outside of history and time?

The start and end of wars endlessly repeat themselves, and this remarkable work by Tavares chronicles the endlessly repeated experience by describing some entangled characters as power sees them. That is, as sometimes useful, sometimes useless… machines.

***

Gonçalo M. Tavares’s A Man: Klaus Klump, translated by Rhett McNeil, is forthcoming from Dalkey Archive Press.

***

Eva Richter, blog editor for Asymptote, holds a B.A. in English and comparative literature, minor in French literature, from Occidental College. She co-produced the dark independent film Redlands, and her fiction has appeared in Columbia University’s Catch & Release.