Read all the posts in Asymptote’s “Mimes” translation project here.

Mime IV. Lodging

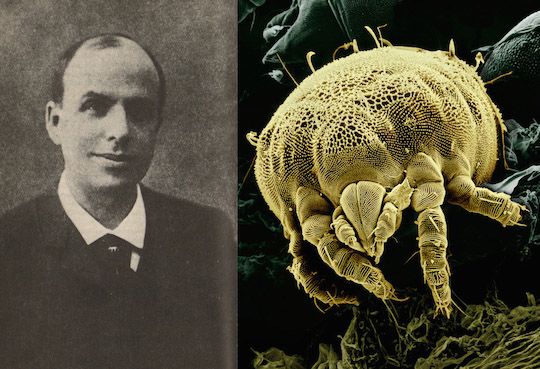

Inn—replete with mites—this bitten, bloodied poet salutes you. This is not to thank you for the night’s shelter alongside a dark track, the mud of which recalls the way to Hades; but for your broken pallets, your smoking lamps. Your oil festers and your galette moulders, and since last autumn there have been little white worms among the shells of your walnuts. But the poet is grateful to the pig merchants who came from Megara to Athens, whose hiccuping stopped him from sleeping (inn, your walls are thin), and gives thanks too to your mites, which kept him awake by gnawing the length of his body, skittering across his cot in throngs.

For he wished—for want of sleep—to inhale the white moonlight through a crack in the wall. And he saw, very late at night, a merchant of women knock at the door. The merchant cried: “Child, child!” But the slave was snoring on his belly, his idle arms blocking his ears with his blanket. So the poet wrapped himself in a yellow robe the color of a wedding veil; this robe, the color of a crocus, he’d been left behind by a cheerful girl the morning she fled, clad in another lover’s garment. And so the poet—in the guise of a maidservant—opened the door; and the woman-merchant ushered in his copious troupe. The last girl had breasts firm like quinces; she was worth twenty minae at least.

“Maidservant,” she said, “I am weary; where is my bed?”

“Dear mistress,” said the poet, “see how your friends have claimed all the beds in the inn; all that is left is the maidservant’s pallet. If you wish to lie there, you are welcome to it.”

The wretched man fostering these sweet young girls lifted the great torch of his lamp, with its many wicks, to light the poet’s face; and upon seeing a maidservant who was neither beautiful nor kempt, he stayed quiet.

Inn, this bitten, bloodied poet thanks you. The woman who spent that night with the maidservant was softer than goose down, and her throat carried the scent of ripe fruit. But all that would have stayed secret, inn, were it not for your pallet’s piercing tittle-tattle. This caused the poet to fear that the piglets from Megara had learned of his adventure. To you who listen to these words, if the oohi oohi of the piglets at the agora in Athens tell the false tale that our poet kept vile trysts, then come to the inn and see the girl with breasts like quinces, the one he managed to take in, though bitten and bloodied by those blessed mites, when the moon was high.

Mime V. The Painted Figs

This earthenware jar—replete with milk—will be offered to the little goddess of my fig tree. I will pour fresh milk over it every morning, and if it pleases the goddess, I will replenish the jar with honey or unblended wine. And so I will honor her from spring until autumn; and should a storm shatter the jar, I will buy another at the pottery market, even though clay is expensive this year.

In return, I pray to the little goddess who guards my fig tree that she might change the color of the figs. Once they were white, tasty and sweet, but Iole tired of them. Now she wants red figs, and swears they will be better.

It is not natural for a white-fig tree to bear red figs in autumn; but Iole wishes it. Have I not shown good grace to the gods of my garden; have I not braided crowns of violet for them and poured them ewers of wine and milk; have I not rustled the poppies for them just when the sun sets the crest of my wall ablaze amid the swarms of gnats humming in the evening air; has my devotion not been worthy of their kindness? If so, goddess, let your fig tree flourish with red fruit.

If you do not listen to me, I will not stop honoring you with daily jars; but I will be compelled to rise at dawn in the fruit season to open the fresh figs with delicate fingers and paint the insides in splendid Tyrian purple.

***

In translating Mimes IV and V, I remained acutely aware of the text’s and the author’s debt to Classics, with the former explicitly inspired by Herodas and the latter a dedicated Classics scholar. As such, I was keen to avoid an overt Anglo-Saxonization of the source, a decision which informed, for example, the use of “replete” for “pleine,” “inhale” for “respirer,” “merchant” for “marchand,” and “replenish” for “emplir.” Of course I broke this rule immediately by translating the first word of Mime IV, “auberge,” as “inn”—here I thought the immediacy of it was amusing and set the wry, quietly bawdy tone that followed, and it seemed more appropriate than “hostel” or “tavern.” The other consideration which informed these decisions was the complex temporal situation: a 2014 translation of an 1890s work set in and inspired by Ancient Greece. A neutral, timeless lexis was therefore attempted in order to keep the English plausible (hence, for example, the omission of “O” in the vocative, which might be perceived as Victorian rather than classical).

In terms of overarching strategies, another I kept in mind throughout the process was the retention of the original’s pithiness. The intricacy comes with the use of simple, well-chosen words and the strange images they conjure, and so I tried my best to dignify this with careful lexical choices in the English. “Foster” came in for “nourrir” because its original meaning is linked to feeding, while “rustle” was used for “secouer” because it is at once more timeless and pleasant-sounding than “shake.” The insertion of “idle” in reference to the slave’s arms was in recognition of the phrase “avoir les bras croisés,” which was current when Schwob was writing and means “to be inactive.” Other solutions were aimed at achieving a quietly poetic effect, such as the ellipsis of “breasts firm like quinces,” or alliteration in “good grace to the gods of my garden.”

Schwob was an expert in slang, and I wanted to nod to this aspect of his authorship with some ludic choices, which I also felt were in tune with the tone of the mimes, e.g., “tittle-tattle,” and the repetition of “replete” in Mime V to mirror the beginning of the previous one. I also couldn’t resist the wordplay of “taken in” for “su prendre” at the end of Mime IV, which seemed to chime nicely with the poet’s gentle dissimulation.

In Mime V, my most prominent intervention was the restructuring of the series of clauses beginning with “Si je…” I judged the “If I…” direct version was too dating, and also thought the “Have I not…” adaptation conveyed the comic indignation of the exhortations more neatly.

***

Sam Gordon is a freelance translator working from French and Spanish into his native English. Currently living between London and Aberdeenshire, Scotland, he completed his BA in Modern Languages followed by an MA in Translation at the University of Bristol. His first novel-length translation, of Karim Miské’s Arab Jazz, is out this summer through MacLehose Press.

***

Image of yellow mite, Lorryia formosa, via Erbe, Pooley: USDA, ARS, EMU