Read all the posts in Asymptote’s “Mimes” translation project here.

Mime II. The False Merchant

A. I will have you beaten, yes—beaten with sticks. Your skin will be covered with spots like a nursemaid’s tunic. —Slaves, bring her over; strike her stomach first; flip her over like a flounder and strike her back. Listen to her; do you hear the sounds of her tongue? —Will you not cease, ill-fated woman?

B. And what have I done, to be brought to the sycophants?

A. Here we have a cat who has stolen nothing, then; she wants to digest at her leisure and rest comfortably. —Slaves, take these fish away in your baskets. —Why were you selling lampreys, when the magistrates have prohibited it?

B. I was unaware of that ordinance.

A. Did the town crier not announce it loudly in the marketplace, commanding: “Silence”?

B. I did not hear the “silence.”

A. You mock the orders of the city, strumpet! —This woman aspires to tyranny. Strip her, that I may see if she is a Peisistratid-in-hiding. —Aha! You were female not long ago. Now look, now look! This is a new sort of marketwoman! Did the fish prefer you that way, or rather the customers? —Leave this young man stark naked: the heliasts will decide if he will be punished for selling prohibited fish in the stalls, disguised as a woman.

B. Sycophant, I beg you to take pity on me and listen. The young girl I love to death is in the keeping of the Long Walls slave merchant. He wants to sell her for twelve minae, and my father refuses me the money. I have lingered too often near the house, so they have shut her away to prevent me from seeing her. She will come to the market with her friends later, but the merchant will accompany them. I disguised myself this way to be able to talk to her: to attract her attention I am selling lampreys.

A. If you give me one mina, I will have you and your friend arrested when she buys your fish, and I will pretend to denounce the both of you, you as seller, she as purchaser; then, shut away at my house, you shall very well mock her greedy merchant until the next dawn. —Slaves, give this woman her dress, because this is indeed a woman (have you not seen?) and her lampreys are false lampreys—by Hermes, these are very large, shiny eels (would you not say the same?). —Insolent woman, go back to your stall, and take care that you sell nothing, for I suspect you still. —Here comes the young girl; by Aphrodite, her body is supple; I will have a mina, and perhaps, by threatening this young man, I may share their bed.

*

In Mime II, I spent some time considering the phrase “manteau de nourrice,” which involves a nursemaid’s/wet nurse’s coat/cloak. The sycophant’s tone chooses “nursemaid,” and the setting in Ancient Greece eliminates “coat.” I don’t imagine that nursemaids’ outer layers were the most likely to get stained, however, given the unlikelihood that a nursemaid puts all her layers on before burping a baby over her shoulder. At first, I chose “shirt,” but that clearly didn’t match Ancient Greece. “Tunic” struck the right balance of truth to the original, historical accuracy, and effectiveness of imagery.

Not inclined toward research on the various currencies of Ancient Greece, I unabashedly stole “mina” and “minae” from A. Lenalie, the work’s first translator. But her approach to Mime II grated on my ear: this is Ancient Greece, so why have the characters speak approximately like they’re in Elizabethan England? In the late 19th to early 20th century, it might have been popular to so alter translations of formal-register, relatively poetic prose like Schwob’s; just think of the poetry of the era. Nor was Lenalie the last translator to impose odd transformations of style on a text. Without conducting further investigation, though, the most I can say is that such essentially transformative translation is out of fashion now.

***

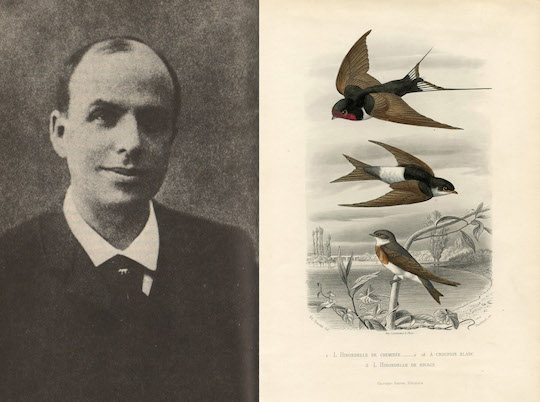

Mime III. The Wooden Swallow

Open up! Child, child, open up! We are the young acolytes of the wooden swallow. It is painted, its head red and its wings blue. We know that true swallows are unlike this one; and, by Philomela, here is one drawing its line in the sky!—but ours is wooden. Child! Open up, open up, child!

Here are ten, twenty, thirty of us carrying the swallow to announce to you the return of spring. There are no flowers yet, but take these pink and white branches. We know that you are cooking spiced tripe, and honeyed chard; yesterday, your slave bought dormice to be jellied in sugar. But keep your feast; we ask for very little. Roasted nuts! Roasted nuts! Child, give us nuts, give us nuts, child!

The swallow’s head is red as the new dawn, its wings as blue as the sky of the new month. Rejoice! The porticos will bring fresh air and the trees will paint their shadow on the prairie. Our swallow promises you much wine and oil. Pour last year’s oil into our pitchers, and the wine into our amphorae; because—listen, child—the swallow wishes to taste them! Pour the wine and oil for our wooden swallow!

Perhaps, as children, you once carried the swallow like us. Yes, the swallow shows us it remembers. Do not leave us waiting outside your door until the streets are lit this evening. Give us fruits and cheeses. If you are generous, we will go on to the next house, where the red-eyebrowed miser dwells. The swallow will ask him for his dish of rabbit, his golden tart, his broiled thrushes; and we will request that he throw us silver coins. He will raise his eyebrows and shake his head. And so we will teach our swallow a song that will make you laugh, and it will whistle all through town the tale of the wife of a red-eyebrowed miser.

*

In the first line of Mime III, Schwob uses the words “enfant” and “les petits” in close proximity. In English, the former is “child” and the latter is a colloquial phrase meaning “children,” literally “the little ones.” The words don’t clash with similarity in the original; by matching the meaning to the context, I avoided creating that problem in translation. Choosing “young acolytes” orients the reader to envision the human children as the speakers, at the same time as it connects with the ritual that they are performing to celebrate helidonismata, a cultural tradition.

Less crucially, I changed some of the foods in Mime III. The inversion of the p’s, i’s, and dental sounds in “spiced tripe” sounded better to me than “un estomac farci,” a stuffed stomach*. The nuts were supposed to be fried, but who ever heard of fried nuts in English? So, to prevent a trivial distraction to readers, I roasted them. This had secondary consequences for the red-eyebrowed miser’s thrushes, which became “broiled” instead of “roasted” for the sake of variety.

***

Blaine Harper studied neuroscience and creative writing at Columbia University. She currently works on Alcatraz Island and is the clinical administrative intern for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

***

*An earlier version of this piece mistakenly referred to un estomac farci as a Persian stomach