It’s a truism to say that translators are an author’s closest readers. They read so closely that they find patterns hidden underneath the text in a manner akin only to psychoanalysis—perhaps more adeptly than a critic or an academic. Coupled with a need to study up on translation craft, this attractive prospect spurred me to sign up for “Kafka in Translation,” a course offered by The Reader and taught by translator Bill Martin in the back of St. George’s bookstore in Berlin.

In our first class, we looked around the folding table curiously as enthusiasts and translators at various professional stages introduced themselves. Some were lucky-ass native speakers, others relative newcomers to the German language, but all of us shared an attraction to the Kafkaesque. Going around the group to share our thoughts, it was strange to be thrown back into a student state so many years after graduating, and I annoyingly immediately found myself in wise-ass mode, ceaselessly sub-clausing and cracking gay jokes.

Over the course of seven meetings, we worked our way through Kafka’s short stories chronologically, reading them in the order in which he published and sequenced them, and studying various translations in order to learn more about the craft, both Kafka’s and his translators’.

Sometimes, we each took a different edition and read them Frankenstein-style, every other line another translator, yet every line still Kafka’s. On the way, we each played favorites, some favoring Joyce Crick—to her acolytes she was always just “Joyce”—and others at times defending the too-often willfully wacky Michael Hofmann (and me? I oscillated between Malcolm Pasley and Stanley Corngold).

We occasionally translated a few stories ourselves, or took them as the starting point of our own creative work (like fellow student Philip Smith’s wonderful piece for BBC radio). Overall, Martin led us in exploring how these stories function through Kafka’s syntax. His language may be simple, but his sentences are anything but, presenting readers (and especially translators) with often-labyrinthine structures that emphasize or obscure their purposes.

The first thing you may have noticed reading Kafka’s very earliest stories is that not all of them are really all that “Kafkaesque.” Entitled Betrachtung, his debut collection reads more like a series of observations than like the progressively more paranoid derailments he became famous for. And though most translations have called it Meditations or Contemplation, the title of the collection can also simply be understood as Looking. When I twigged to that (especially in connection to HBO’s recent foray into gay life in the Bay Area), my antennae were set awiggle; these early tales all did share a certain voyeuristic element. The most famous one of these is perhaps “The Passenger,” in which the narrator marvels at the entirely unself-conscious physicality and presence of a black woman standing next to him on a tram. In other stories, windows feature frequently, as does the idea that impressions might be deceiving.

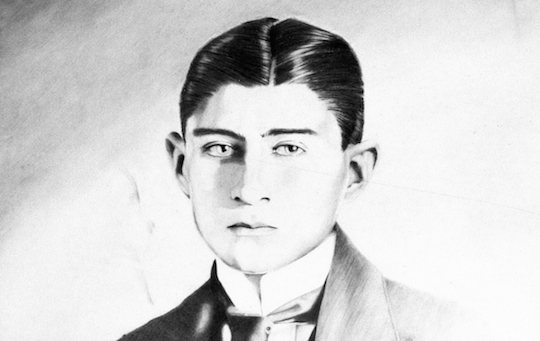

Courtesy of Christiaan Tonnis, Flickr CC

The book starts with an odd (even for K.) little piece, “Children on a Country Road,” in which a boy narrator seems to prefer watching the traffic pass by on the country road outside over playing in the woods with his peers. Though he seems to eventually immerse himself into their preteen spirits, running, tumbling, and singing as one, the story ends as follows:

Our time was up. I kissed the one next to me, reached hands to the three nearest, and began to run home, none called me back. At the first crossroads where they could no longer see me I turned off and ran by the field paths into the forest again. I was making for that city in the south of which it was said in our village:

“There you’ll find queer folk! Just think, they never sleep!”

(Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir)

Cities have always attracted queer folk, and, though I don’t know about in Kafka’s era, after the Iron Curtain came crashing down the writer’s native city of Prague became a sex tourism hotspot for men from all over the world. With the age of consent at 15, and the young populace painfully broke (especially in comparison with the newly accessible West), the sex trade became a major part of the city’s economy in much the same way that it was back in Weimar-Republic Berlin.

This is painfully visible in artist and filmmaker William E. Jones’ The Fall of Communism Through Gay Pornography (too heartbreaking and NSFW to embed here), in which you can clearly read the sudden breakdown of the Soviet Union off the faces of young men performing in porn that was distributed around the world.

In Christopher and his Kind, author Christopher Isherwood takes himself to task for portraying the lives of sex workers (and his own admittedly predatorial role as a foreigner) with far too breezy a tone in his famous Berlin stories. The reality was much more grim and one imagines the haunting interviews in the 1994 documentary Body Without Soul (watch the trailer below) were as true in the 1990s as in 1930s Berlin and in all the current countries where people are exploited by men carrying foreign currency.

Was it a surprise, then, that when I set myself to translate the next story in Kafka’s Looking, “Entlarvung eines Bauernfängers,” conventionally translated as “Unmasking the Confidence Trickster,” that I went for “Revealing the Hustler” instead? That slight lexical shift transformed the story immediately, all the elements falling in line, the parts playing together well, if, perhaps, for a whole new team. You can read my attempt below, and with really only that titular term tweaked to include a queer dimension, what was previously just subtext now stands out starkly proud.

The main effect of this is that a story usually translated (and thus understood) as one unmasking a con man, now seems to tear back the mask stuck to the narrator’s face instead. Its final lines (closely connected to the etymological element of “larva” in the German title’s Enlarvung), now seem to reveal a far queerer butterfly than the big tall man emerging at the end of most—let’s just say—more heteronormative translations.

Yet my translation is not meant to “read,” in the Paris is Burning sense, K. as gay. Instead, I hope it shows just how much the translator’s personal assumptions and inclinations can impact not just the text’s tone, but the author/narrator’s sexuality. With the weight of an indistinct guilt hovering so heavily over all of Kafka’s work, it is maybe too easy to see him as just another boy who wanted to run away and join the city’s fairies. Yet one can totally read “Entlarvung” as a painful tale about the man who believes he has outgrown that boy and all his little gay dreams. Seeing himself like the monstrous insect in Metamorphosis, the man would rather pretend to be normal than to join his fellow freaks cruising along the side streets and sidewalks.

Now, I know, outing a dead author is as fashionable as diagnosing them with some debilitating malady. It is a laser pointer taking aim at the source of all that beauty, at the hurt from which their art must’ve sprung. It’s all part of dealing with the mystery of art—where does it come from?—and it’s no surprise that we’d sooner pathologize artists than admit that blind fate might be the ultimate curator, or that some might just be more gifted or hard working than others. Others meaning us, of course.

Embracing them as queer or gay is not always a pathologizing trick though; more often it is a way to expand our community retro-actively, to recruit from the past to bolster our future. With Kafka on our side, we can own the self-hate, we can own the hetero paranoia, we can own the repression, and we can see it all as the fucked-up Kafkaesque illusion we hope it to be.

As one of the other students exclaimed at our final meeting, dedicated of course to K’s most famous story, The Metamorphosis: Why can’t we believe that Gregor Samsa doesn’t get swept up by the maid at the end? That instead he morphs into his true self, an indescribably beautiful butterfly soaring over Prague and watching with a forgiving flutter the family that stopped supporting him when he turned out to be unlike the son or brother they had wanted him to be. That’s a transformative translation I’d like to read.

*****

Exposing the Hustler, by Franz Kafka

Translated by Florian Duijsens

Finally, close to ten o’clock at night, accompanied by a man I’d only fleetingly encountered before but who had unexpectedly latched on to me again and dragged me around the streets for two hours, I arrived in front of the stately home where I’d been invited to a soiree.

“So!” I said and clapped my hands together to signal the absolute necessity of parting. Several, less explicit attempts to do so had preceded this one. I was getting really tired.

“Must you go straight up?” he asked. In his mouth I heard a sound like the clashing of teeth.

“Yes.”

I had been invited after all, I had told him so immediately. But I’d been invited to come up, where I would have so liked to be, not standing here at the gate below and looking over the ears of the man standing opposite me. And now falling silent with him even, as if we had decided on a long stay at this spot. The houses all around us took up their parts in this silence as well, and so did the darkness above them up to the stars. And the steps of invisible passersby, whose paths you did not feel like guessing at; the wind, again and again pressing itself to the opposite side of the street; a gramophone, singing to the closed windows of a room somewhere—they sounded out of this silence as if it had been theirs for always and forever.

And my companion settled in, first in his and—after a smile—also in my name, stretched up his right arm along the wall and rested his face, his eyes closing, up against it.

I did not see his smile out until the end though, for shame suddenly turned me around. Only from this smile did I come to recognize that he was a hustler, nothing more. And I’d been in this city for months at this point, had believed I knew these hustlers through and through, how they would come out at night from side streets, hands outstretched, approaching us like hosts, how they’d hang around the advertising columns like the one we’re standing next to, as if playing hide and seek, spying on us from behind the curve of the column with at least one eye, how at street crossings, when we became anxious, they’d suddenly float in front of us on our side of the sidewalk! I understood them so well, they were after all my first acquaintances in the city’s little bars, and I could thank them for my first look at a toughness that I now could barely imagine not being a part of my world, so much so that I had already begun to feel it in myself. How did they still remain right in front of you, even when you had long since run away from them, when there was really no longer anything left to catch! How did they not sit down, how did they not fall, instead just looked at you with glances that were still always persuasive, if only from afar! And their means were always the same: They stood in front of us, their chests puffed up; sought to keep us from where we aimed to be; prepared for us instead a home in their own hearts, and if the collected feelings then finally reared themselves in us, they took this as an embrace in which they threw themselves face first.

And these old tricks I’d now recognized only after spending so much time together. I rubbed the tips of my fingers together to undo the disgrace.

My man still leaned here as before though, still held himself like a hustler, and his satisfaction with his fate reddened his free cheeks.

“Gotcha!” I said and gave him a light tap on the shoulder. Then I rushed up the stairs, and the so baselessly loyal faces of the help up in the vestibule were pleasing like a nice surprise. I looked at all of them in turn as they took my coat and dusted off my boots. Breathing out and stretching tall, I then entered the hall.

***

This translation wouldn’t exist without my fellow students and the wonderful advice of Bill Martin. Image courtesy of Chris Bartle, Flickr CC.

***

Florian Duijsens has lived in Berlin since 2007, working as a freelance academic editor and as a music, food, and travel writer (for National Geographic Traveler, the Guardian, Stil in Berlin, amongst others). He is the Senior Editor of Asymptote, an online journal for literature in translation, the Fiction Editor of SAND Journal, and teaches at Bard College Berlin.