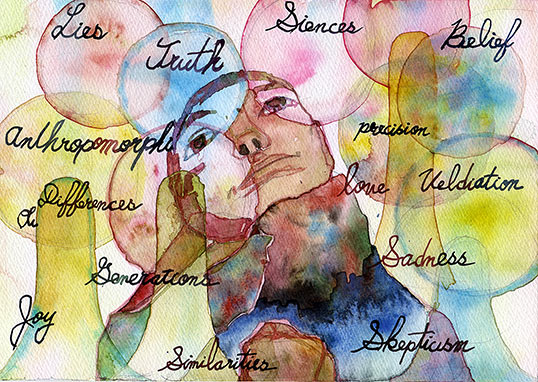

Gonçalo M. Tavares’ “Brief Notes on Science,” translated by Rhett McNeil in our newest issue, is a curious venture into the semantics of scientific enterprise. With wit, insight, and exactitude, the allegorical tries on a technical job: defining and sketching out the surprisingly ambiguous nature (and purpose) of science.

Danger

It is clear that Danger is the origin of the most efficient scientific methods.

If Man were immortal, he would not yet have invented the wheel (one could say).[…]

Skepticism and Belief

Skeptic like the skeptics, believer like the believers.

The half that advances is the believer, the half that confirms is the skeptic.

But the perfect scientist is also a gardener: he believes that beauty is knowledge.

(The beautiful person holds a secret. She has discovered something.)

Those who read literature have to deal with these questions all too often: what is literature? And what’s it for? But despite having been an equally human invention, scientists typically find their realm unquestioned, its limits defined simply through the parameters of the scientific method.

The River

What fraction of knowledge is enough for me to be happy?

What fraction of knowledge is enough for me to make others happy?

Is that which science discovers outside of these two fractions the part that is useless?

But in “Brief Notes on Science,” Tavares carefully inverts the apparent dichotomy of observed-versus-imagined worlds. Metaphors, allegories, and—most importantly!—stories explain the tenets of a discipline proudly reliant on empirical evidence. Invoking folktale tropes, such “as in the children’s tale, you leave a trail of breadcrumbs to find your way back” these elucidations, presented as sub-categories, engender widely recognizable anxieties, hungers, discomforts and nostalgias to prefigure the plausibility of quantifying “real” experience.

Differences and Similarities (1)

Spotting the differences is one of the methods. Spotting the similarities is another.

The mosquito that disturbs your harmony of sound and space, when it is smashed between your swift hands, becomes silent—just like your hands after the action. Thereafter you throw away the mosquito, and the harmony of sound and space returns. But don’t imagine that it is definitive, this harmony. You know very well that it is not.

Differences and Similarities (2)

We can kill the mosquito or point at it and say: Mosquito.

Classifications and categories begin with disharmony.

Though he invokes folktales alongside theories of unstable language, Tavares’ nonfiction isn’t quite parable. To deem it so would be to dampen its smarting, prickly originality. Despite the storytelling motif, “Brief Notes on Science” rests firmly locked in physical tactility. But Tavares’ startling insight into how the disruptions of palpable existence, and the different ways we explain them (perhaps through history, literature, or empirical research) undermine the dualistic notion of abstract versus concrete. Instead, Tavares insists on an equally absurd and boundlessly fascinating real world that humans grasp in ways that are seemingly different, but truly the same.

***

Read “Brief Notes on Science” in our April 2014 issue here.

***

Gonçalo M. Tavares was born in Luanda, Angola, in 1970 and teaches theory of science in Lisbon. Nobel Laureate José Saramago stated: “In thirty years’ time, if not before, Tavares will win the Nobel Prize, and I’m sure my prediction will come true . . . Tavares has no right to be writing so well at the age of 35. One feels like punching him.” In 2005 Tavares won the José Saramago Prize. His novel Jerusalem was also awarded the Prêmio Portugal Telecom de Literatura em Língua Portuguesa 2007 and the LER/Millenium Prize. His novel Learning to Pray in the Age of Technique received the prestigious Best Foreign Book Prize 2010 in France.

Rhett McNeil is a scholar, critic, and literary translator from Texas, where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa from UT-Austin with degrees in English, Portuguese, and art history. He has an MA in comparative literature from Penn State University and is currently finishing a Ph.D. in the same department, with a doctoral minor in aesthetics. His translations include novels and short stories from some of the most innovative and accomplished authors on the world literary scene, including António Lobo Antunes, Enrique Vila-Matas, and Gonçalo Tavares. McNeil also edited and translated a volume of short fiction by the Brazilian writer Machado de Assis. His translation of Tavares’s Joseph Walser’s Machine was longlisted for the 2013 Best Translated Book Award.