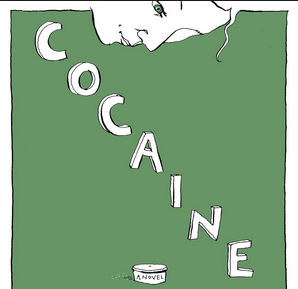

It should come as no surprise—if titles mean anything at all, that is—that Pitigrilli’s Cocaine was banned shortly after its 1921 publication. The slim Italian novel is not short on the white stuff, and it doesn’t skimp on the excesses we associate with its sniffing: sex, orgies, general underworld shadiness, all glimmering with the luster that illicit substances (if only through their very illicit-ness) can provide.

To readers in 2014, the novel’s purported depravity may appear mellowed, but Cocaine shocks the system all the same. The real blow in reading this nonagenarian novel, rereleased in a new translation by Eric Mosbacher through New Vessel Press, is its stomach-turning linguistic smarts that elevate this by-turns insightful and nonsensical tale to M.C. Escher-esque levels of depth. Cocaine isn’t about the drug, after all: storming through the not-quite surreal, the book reveals the addictive authority of the words we use.

I picked up Cocaine only vaguely intrigued by its history: published in Italy in 1921 by Dino Segre (pen name: Pitigrilli), the novel was promptly, and predictably, banned by the Catholic Church, which cited its depraved and all-too-offhand depictions of drugs and sex. Perhaps similarly expected, given the controversy, was the book’s commercial success: at the time of its publication, Cocaine was translated into eighteen different languages. Since then, the work has been largely forgotten in non-Italian circles: Mosbacher’s version is the novel’s first translation since the 1980s.

Though its backstory is conventional, Cocaine is not. The novel focuses on an ex-medical student named Tito Arnaudi (who abandoned medicine because he was not allowed to sport his monocle during pathology exams). Tito relocates to the center of party-hearty high culture, Paris, and, through an uncle in America (“you mean American uncles actually exist?” Tito’s friend muses) finagles his way into a newspaper job, where he invents stories billed as reporting for a rag fittingly titled the Fleeting Moment.

Tito’s first real assignment is an in-depth exposé of Parisian cocaine dens, and Tito dives headfirst into his métier, developing two vicious dependencies in the process. Naturally, Tito becomes addicted to cocaine, but his increasingly obsessive love affairs—with Kalantan, an Armenian widow who insists on coffin love-making, and with Maud, his hometown sweetheart-turned-obsession—consume the plot and bring about Tito’s demise. Tito’s story follows the drug-story trope we all know: youngster with gumption succumbs to vice, glows with initial euphoria, suspects creeping psychological despair, concludes with a bitter and inevitable end. Of course, the story is a lot more twisty-and-turny than that, but it really isn’t the story that matters.

We’re all familiar with the words typically employed in book reviews, and I would arguably be quite justified in employing them here: at its heart, Cocaine is a biting satire, its storytelling is a lively jaunt through postwar society, the prose remains fresh, the insight lucid, the humor darkly comic and (truly, I mean this) laugh-out-loud funny.

I’d avoid relying on these clichés if not for their necessity writing this review. These words are so frequently used that they are virtually meaningless and do nothing but affirm that I am a smart literary person writing a glowing literary review. They do not mean anything and hardly reflect the truth in Cocaine: like Tito, I’m lying, inventing certainty through transparently arbitrary words, and my flagrant laziness is just another way to invent with language. Tito would agree with me here: reading the book of Genesis, he opines:

“What a jester, what a humorist God is:

God said: ‘Let there be light

Let there be heavens

Let there be grass

Let there be trees[…]’

If that was how Creation was done then it was not very hard work… I think the Almighty likes parlor tricks and arranged the whole thing beforehand.”

Like God (there’s blasphemy!), Tito creates realities through the words he spills, causing disasters and suicides by lazy reporting, misinforming the masses. Cocaine muses on hallucination through words. In the beginnings of his post-euphoric slump, Tito poetically and pathetically realizes his words’ growing futility: he is nothing but body: “I’m sick of knowing that my body’s a laboratory designed to nourish and renew my protoplasm. I’m nothing but phosphorous, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon.” But even in invoking the physical world’s most elemental components, Tito resorts to abstraction.

Cocaine oozes with meta-musings on writing, thinking, and meaning, and the very notion of translating Cocaine seems to undermine its fundamental linguistic absurdism. But Eric Mosbacher’s translation succeeds: the writing is bright, funny, and smart. Cocaine should be required reading for comp lit undergraduates, stand-up comedians, and seasoned linguists. Here is a novel we deeply want to take seriously, but we can’t, and we feel silly in attempting to do so. Cocaine is doublethink reminding us that every word we live by is—at its core—fiction.

***

Pitigrilli’s Cocaine, translated by Eric Mosbacher, is available from New Vessel Press.

***

Patty Nash, blog editor for Asymptote, studied French and comparative literature at the University of Oregon before moving to the south of France and leading a charmed and writerly life, for now. She tweets at @pattynashdj.