Asymptote Blog is celebrating The Great Gatsby’s 89th anniversary with two essays dedicated to Gatsby, translated: What does a seminal work of 20th-century Americana look like outside the tight nexus of American lit? This essay, second in a two-part series, takes a look at four very different Gatsbys, in translation and onscreen. Read Part I here.

***

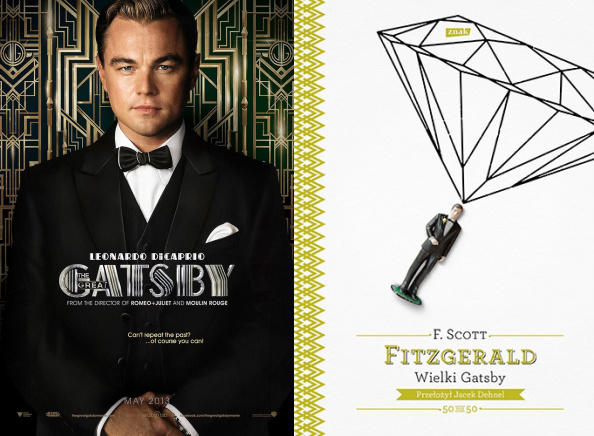

“Alcoholism, insomnia, anxiety, depression”: this is the diagnosis that appears in the medical record of Nick Carraway, protagonist of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 film “The Great Gatsby.” Luhrmann’s is the fourth filmic Gatsby, published on April 10, 1925, and one of the first works tackling the mythic American Dream.

In Poland, The Great Gatsby didn’t appear until 1962 in Ariadna Demkowska’s translation; another translation, by Jędrzej Polak, was issued only once, in 1994. In 2013, i.e. over half a century after its Polish premiere, Fitzgerald’s novel came out in Jacek Dehnel’s new translation. I will focus on two film adaptations and two Polish translations: the 1974 film directed by Jack Clayton and the 2013 Baz Luhrmann version; and translations by Ariadna Demkowska and Jacek Dehnel.

In Jacek Dehnel’s fresh take, Fitzgerald’s novel appears as a much less smooth-reading and conventional piece of writing than in Ariadna Demkowska’s translation. It suddenly brims with unexpected epithets and reveals new facets of well-known images.

Fitzgerald’s storytelling also appears in a new light. This is quite crucial, bearing in mind the literature of the lost generation that, according to Gertrude Stein, reveals the falseness of language incapable of expressing the brutal cruelty of wartime. Jacek Dehnel’s translation of the The Great Gatsby reveals above all the impotence of words as characters try to take control of their lives.

The most striking example is the form of address constantly used by Jay Gatsby “old sport.” Demkowska translates it as “mój drogi” [“my dear”] while Dehnel chooses the archaic “stary druhu” [roughly “old companion”]. The conventional “mój drogi” doesn’t do justice to the tragic deception that James Gatz, the son of poor farmers from North Dakota, attempts to perpetrate. He uses “old sport,” borrowed from his benefactor Dan Cody, to inspire confidence in the offspring of an illustrious family, an heir to “Old Money,” an Oxford graduate, a respected citizen. When it transpires that Gatsby had spent barely a few months in Oxford and had earned his fortune through shady dealings, “mój drogi” fails to produce the same pathetic, grotesque effect as “stary druhu.”

Demkowska corrects the diction of the babbling drunken guests at Gatsby’s parties and applies political correctness in that she deletes the word “Jewess” from the description of Meyer Wolfsheim’s secretary and gets rid of Wolfsheim’s mistakes in pronunciation and syntax. While these few examples cannot adequately express all the differences between the two translations of Fitzgerald’s novel, the main point I want to make is that in Dehnel’s translation it becomes a very different book.

On the other hand, I also ought to mention the depiction of New York as a city “all built with a wish out of non-olfactory money.” Demkowska renders this as “a city built out of dreams, with money that doesn’t stink” [“miasto zbudowane z pragnień, za pieniądze, które nie cuchną” (p. 90)], while Dehnel translates it as “a city built by means of dreams out of odorless money” [“zbudowanym za sprawą życzenia z bezzapachowych pieniędzy” (p. 85)]. In this instance, Demkowska’s image seems much more vivid and directly references the Latin saying.

Overall, Dehnel’s translation brings out the humor and richness of language, and highlights the sophisticated narrative structure of Fitzgerald’s novel. As one critic has noted, the plot is quite simple but by using the narrator to gradually reveal the hero, the novel seems much more complex than it really is.

By making the narrator a more flesh-and-blood character, Dehnel creates a world completely different from that of Ariadna Demkowska’s translation (in which Daisy’s cousin and Gatsby’s friend appear almost transparent). Nick organizes the narrative structure, making it more subjective, changing the chronology and adopting a more dramatic approach to constituting the organizing consciousness.

This “organizing consciousness” also appears in Baz Luhrmann’s film. Luhrmann explicitly highlights Nick’s central status: the film opens with him visiting a psychiatrist, who has been treating the hero for the condition tormenting him since his friend’s tragic death. (The psychiatrist character might be a reference to another of Fitzgerald’s novels, Tender Is the Night).

The doctor recommends that Nick write his memoirs: “writing has a calming effect,” he says. Letters, words, sentences appear on the screen, first drawn by a trembling hand, then typewritten. This old-fashioned narrative device not only emphasizes Nick’s presence, but stresses the audience’s simultaneous acts of reading.

“The restlessness [of the city] approached hysteria,” Nick writes. Luhrmann’s film succumbs to visual hysteria. There is too much of everything here, the film’s frame seems to be bursting with an abundance of colors, shapes, constantly changing and pulsating.

Tautology is another organising principle and Luhrmann stages some of the scenes from the novel in a very literal way. As Nick enters the room where Daisy and Jordan are lying on a sofa, we see the curtains blow in the breeze, enveloping the women in a soft white veil. The scene seems to be a few seconds too long, the curtains are flapping with a delicate female hand with a huge diamond ring emerging from behind them

Luhrmann loves exaggeration, yet he is also very consistent in using one of Fitzgerald’s narrative devices: Nick relates the events in close-up, so to speak, with the visual acuteness of a film camera. This highly subjective way of telling a story enables the audience to see the raindrops streaming down Gatsby’s face, Tom’s fury and Daisy’s restlessness. Every expression appears as if under a magnifying glass.

In Clayton’s film, based on a screenplay by Francis Ford Coppola, the main driving force is money. The house, a Gothic Southern mansion, belongs to Daisy, who warns Nick that Jordan won’t marry him “of course—it will just have to be an affair,” while she herself didn’t wait for Gatsby’s return from war because she understood that “rich girls don’t marry poor boys.” Coppola and Clayton make the relationship between the two main characters conventional, turning their reunion into a melodramatic adventure while everything in their world turns on whether you have money or not.

Luhrmann’s take is quite different: his film, just like Fitzgerald’s novel, is in Edmund Wilson’s words “a vague gesture of resistance.” It is no accident that windows feature constantly: during his therapy sessions Nick looks out of the window at the weather; Gatsby observes his neighbour and his guests through the window.

The characters inhabit a world that to them feels alien, hostile, devised by someone else. A striking image from Fitzgerald’s novel keeps recurring in the film: the abandoned and tattered billboard advertising the services of a Queens oculist looming over the Valley of Ashes. Wilson, the wretched car mechanic, sees in this face the face of God.

Baz Luhrmann’s film plays not just with the well-known earlier adaptation of Fitzgerald’s novel but also with cinema. Gatsby’s death evokes that of Charles Foster Kane: his dying scene includes a close-up of the hero’s lips and we hear him whisper the word: “Daisy,” recalling Orson Welles’ famous “Rosebud.”

The list of filmic references could go on, but I want to focus on Luhrmann’s strategy. Luhrmann shows that it is precisely due to its imagery—expansive, exhausting, teetering on the brink of kitsch—that Fitzgerald’s novel chimes with present-day sensibilities. Just like the novel’s protagonist, Jay Gatsby, on the brink of ridiculousness as he waxes lyrical about his European journeys, his time in Oxford and his wartime achievements, Leonardo Di Caprio’s Gatsby is as pathetic as he is tragic: his bravado seems unbearable, but there is something deeply moving about a character who has such faith in his fight for happiness.

In a letter to a friend dated August 9, 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “Also you are right about Gatsby being blurred and patchy. I never at any one time saw him clear myself—for he started out as one man I knew and then changed into myself—the amalgam was never complete in my mind.”

Unlike Clayton’s Jay Gatsby, Luhrmann’s Gatsby is no romantic dreamer longing for the past. In the 2013 adaptation the main character is not Gatsby but Nick, a man painfully aware of the fact that people no longer dream the way Gatsby dreamed. While Clayton’s film overflows with nostalgia, Luhrmann’s version does so with the awareness of the absurdity of the world, where we can’t really make our mark, condemned to the role of a passive observer of other people, events and himself.

There are a surprising number of convergences between the two readings of Fitzgerald’s novel in the second decade of the 21st century. Assuming (and there is little reason not to) that both the translation and the film adaptation are individual interpretations of the novel, we can say that Luhrmann and Dehnel read “The Great Gatsby” in a similar way: not only as a story of lost illusions but also of the impossibility of escape from melancholy and despair.

***

Translated by Julia Sherwood, Asymptote’s Slovakia editor-at-large.

***

Olga Katafiasz teaches theatre and film studies at the Theatre Directing Department of the Ludwik Solski Theater School in Krakow. From 1995 to 2008 she worked for the journal “Gazeta Teatralna Didaskalia,” where she continues to publish her essays and reviews. She is the author of several studies on the links between literature, theatre and film, as well as several books, including Próby wrażliwości. Szekspirowskie ekranizacje Laurence’a Oliviera i Kennetha Branagha (2005) (Tests of Sensibility. Laurence Olivier’s and Kenneth Branagh’s film adaptations of Shakespeare, 2005), Słownik wiedzy o filmie (Dictionary of Film, co-author Joanna Wojnicka; 2005, 2009), Shakespeare i kino. Strategie adaptacyjne i ich konteksty społeczno-kulturowe (Shakespeare and Cinema. Strategies of Adaptation and their socio-cultural context 2012).

This text is an abridged version of a talk the author gave as part of her Ph.D. presentation at the Jagiellonian University of Krakow.