The word bridge comes from the words log and beam; the earliest bridges were trees that fell over and connected two opposing banks. The wood beams that make this bridge, the Ponte Coperto in Pavia, Italy, are exalted in the vault, their circumference larger than any neighboring tree. The columns that support this vast lid were exhumed from a mountain of granite, their chisel marks and eased edges the distilled labors of a multitude of hands. Up close, they are heavy, rutted, imperfect—but from a distance the columns stand delicately, twenty-four strong on each side of a thickened waist. The roofed colonnade is held by four arches that touch the river in three places below. The sense of solidity underfoot is echoed overhead, shelter and possibility both made new in the connection.

The Ponte Coperto reincarnated three times in the same location. It was built originally by the Romans; the remains of that are now a portly grass-covered stub on the opposite shore. The Roman bridge had to be rebuilt in the 14th century, and stood steadfast until it was bombed beyond repair in the Second World War. Rebuilding it took no less than four years, and despite the financial devastation caused by war, no expense was spared. Its sidewalls form parapets sufficiently generous to double as elevated benches. Iron railings create parenthetical openings along the heft of an otherwise solid line. The Madonna is stationed in a chapel at the bridge’s center—candles are lit for her in continuous vigil.

People traffic the bridge in the way that birds flock to roofs or power lines, in a communal pause at the midpoint of their flight. Apart from its uninhabited depiction on glossy postcards, I have not yet seen the bridge devoid of people. Sometimes on warm summer evenings, the openings at both ends of the bridge are closed and tables are rayed across its stone street. Residents entertain their visiting guests under the protection of its eaves and enjoy the gentle breezes that waft from the water flowing below. In September, during the “Notta Bianca,” the White Night, the town stays up all night to simultaneously commemorate and mourn the end of summer, and few miss the occasion to show off their tans. The small city of Pavia swells as thousands flood in from the provinces.

I am unable to walk across this bridge without recalling the aura of another bridge—a bridge I have never actually seen—but one whose characters, stories, and tragedies loom in my mind like plaintive ghosts. The bridge I am speaking of is the one eulogized by the Yugoslav writer Ivo Andrić in The Bridge Over the Drina. The book was recommended to me, in the best kind of way, by an architect whom I met briefly after I first moved to this place. My new acquaintance Stefano and I were discussing the work of Aldo Rossi, an Italian architect in whose shadow many young architects of Stefano’s generation have struggled to find their own light. He told me he thought Rossi’s book, Architecture and the City, a staple of post-Modernist thinking, was a plaigarization of Andrić’s masterpiece.

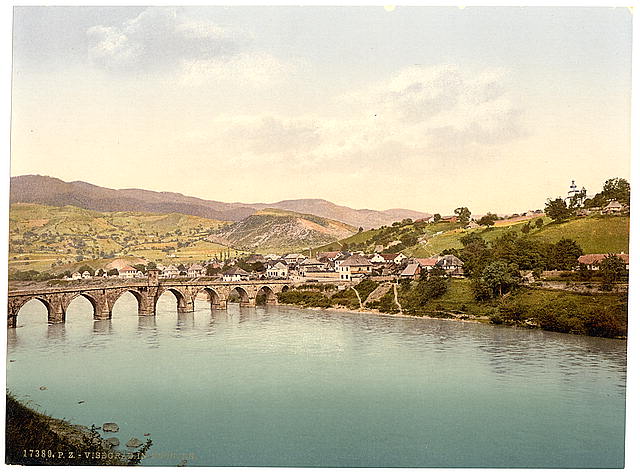

The eponymous protagonist in Andrić’s book is an actual bridge that was built in the small Bosnian town of Višegrad in the 16th century at the bequest of a Turkish Grand Vizier. The River Drina was the blue ribbon on the map that divided the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires. The vizier who financed the bridge had been born in Višegrad, but during the levy of Christian subjects by the Sultan, was stolen from his mother and carried across the Drina in a boat to the Turkish shore. A sharp and competent boy, he quickly rose in the Turkish government; but though he became the Grand Vizier, a man of great wealth and power, he was forever haunted by that moment of separation from his mother. He built a bridge across the river at the exact point where he had been rent from her arms.

More than a backdrop or theater for the life of the town, the bridge is implicated in the town’s unfolding fate. The fantastic tales of the townspeople are embroidered into its sinews as firmly as the mortar that binds its bricks. Their lives are inseparable from the life of the bridge; they are characters written into the same legend. That bridge, and the covered bridge in my newly adopted home in Pavia, mend more than a river’s opposing banks. They magnetize memory, they are the body of story—they fasten the imagination to solid ground.

Perhaps Andrić’s characters return to me so vividly because I read his book before I was able to accrue much of my own experience on the Ponte Coperto. His characters took up residence in my mind before I had a chance to inhabit the place with stories of my own. Or perhaps his telling of the story sensitized me to the departed presences that hover invisibly along the bridge’s long corridor. The layers of history, the candles and their insomniac glow—dignified repose straddling somnolent waters.

Pavia’s Ponte Coperto fell twice yet continues to rise up renewed, like a Japanese shrine that is dismantled and rebuilt every twenty years. The temple rebuilding ceremony is simultaneously a physical acknowledgment of impermanence and a way to pass ancient building techniques on to the next generation. The destruction of the temple allows for the continual renewal of the craft of building. The physique of the temple remains constant over time, because of the cyclical influx of fresh new energy in an interdependence in which the life of the people is bound to the life of the building; a ritualized reminder that there is no permanence without maintenance.

Somehow this covered bridge has been able to overcome every disaster and withstand every flood. Because it, like the one that spans the Drina, possesses a “strange harmony” in its forms and “a strong and invisible power in [its] foundations,” which enable it to emerge from every test unharmed. The secret to these bridges’ invisible power, like that of the Shinto shrines, is that both are crystallized labors of human lives. Human lives whose memories help stabilize their solid foundations. Permanence here is not stasis, but stubborn resistance that lengthens the horizon of time itself.

***

Sarah Robinson practiced architecture in the San Francisco Bay Area for twenty years. Her books Nesting: Body, Dwelling, Mind (William Stout publishers 2011) and Mind in Architecture, with Juhani Pallasmaa (MIT Press, forthcoming) explore how our perception is shaped by the built environment. She now lives and practices architecture in Pavia, Italy.

Image via the Library of Congress. Višegrad, Bosnia, Austro-Hungary, ca. 1890 and ca. 1900.