Click back to see Part I and Part II of this series. Or you can enjoy this post all on its own!

*****

The translation of the language of things into that of man is not only a translation of the mute into the sonic; it is also the translation of the nameless into name. It is therefore the translation of an imperfect language into a more perfect one, and cannot but add something to it, namely knowledge.

— Walter Benjamin, “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man”

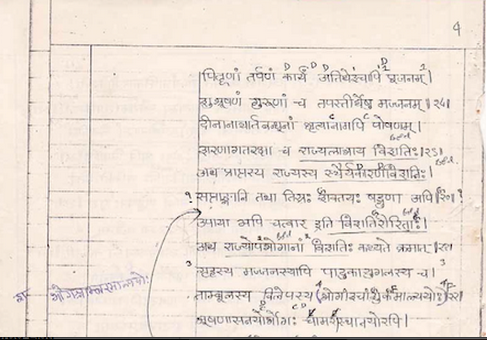

In my previous posts I discussed the dangers of reading Asian encyclopedias by discussing two fictional representations of Asian systems of knowledge. Today, I return to reality by looking at a very real, very dear-to-me Indian encyclopedia, the Mānasollāsa of the 12th century South Indian king Someśvara III. It is the first general accounting of the various forms of scientific knowledge we find in pre-modern India. Topping 8000 verses, it is monumental, true to Aude Doody’s definition: “a grand-scale reference work with retrieval devices.” Because of its massive scope, it has not yet been fully translated into English or any other language (though sections have been translated into Kannada).

The Mānasollāsa is divided into five major categories, each containing twenty chapters. The work is thus comprised of an attractive hundred sections. Making the work encompass a round number leaves some topics disproportionately represented in the table of contents. While “shoots-and-ladders” may not occupy an proportionate place in most people’s lives, in the opening pages of the Mānasollāsa, they do. The structure is explained in a table of contents (granthasaṁkṣepaḥ) at the beginning of the work:

First are the twenty means of obtaining kingship. After kingship has been obtained, there are the twenty means of stabilizing said kingship.

Once kingship has been stabilized, there are the twenty enjoyments of kingship, and also the twenty amusements that bring joy.

Then the twenty modes of play that produce pleasure. Now I will explain the condensed contents in the same order.

Obtaining Kingship— One should avoid untruth, cheating, women who shouldn’t be approached, and food that shouldn’t be eaten. (4)

Avoid jealousy, conference with the fallen, anger, and self-adulation. (8)

Give generously, speak king words, do those actions which are done for the fulfillment of desires (aka sacrifices), worship the gods without restraint and satiate cows and Brahmins. (13)

Honor the forefathers, honor guests, pay attention to gurus, and bathe in sacred rivers

Support relatives, the sick, the poor, orphans, and servants, and protect those who seek refuge. (20)

Stabilizing Kingship— There are twenty means of stabilizing kingship once it has been obtained. These are divided as such— The seven limbs, the three powers, the six qualities, and the four means. They are explained in order:

The Seven Limbs— Lordship, ministers, allies, the treasury, the countryside, fortresses, the army.

The Three Powers— Influence, enthusiasm, good advice.

The Six Qualities— Subjects, guilds, pacts, divisions, setting out for attack, the two-fold seat of power.

The Four Means— Creating competition, punishment, kind words, incentives.

Next the twenty methods of enjoying kingship are told in order—

Joys of Kingship— The joy of the house, of bathing, of shoes, of betel-nut, of ointments, of clothes and garlands (7)

The joy of jewelry, seats, flywhisks, arranging the court, children, food and water. (14)

The joy of foot massages, drinks, umbrellas, beds, incense, and women. These are the twenty types of enjoyments.

Amusements— Now that the twenty joys have been explained, the amusements are enumerated. There are the amusements of weapons (śastra), intellectual discourse (śāstra), elephants, and horses. (4)

The amusements of wrestling, numbers, cockfights, quails, sheep and bulls. (10)

The amusement of pigeons, dog racing, hawks, songs and musical instruments. (17)

The amusement of dance, stories, and magic. These are the twenty amusements for pleasure. (20)

Games of Kingship— Now the twenty games that bring joy are explained in sequence. There is play in the mountains, in pleasure-gardens, on swings, in the water, and in sprinklers. (5)

Play on lawns, in the sand, in the moonlight, in groves, in drinking halls, and with riddles. (11)

Chess, dice, cowries, shoots-and-ladders, games with torches, in the dark, games suitable for heroes. (18)

The games of love (prema) and sexual pleasure (rati). (20) These are the five divisions and 100 subdivisions.

This is the table of contents. Using these hundred branches I will describe that greatest of all wish granting trees, the extensive tree with many seeds that is the aforementioned Mānasollāsa.

Beyond the table of contents, however, these neatly arranged sections are not equally represented. The section on umbrellas (3.17) is far shorter than the section on the palace (3.1), for example. And some sections that would appear to be quite important (say, the very first section, which deals with avoiding untruth in pursuit of obtaining kingship), are in fact quite short.

Other large passages that might merit their own standing are oddly sub-categorized. The massive section on enjoying and arranging a palace (3.1) contains long passages addressing the aesthetics of painting (the proper proportions, standard iconography, etc). Why is a section like this not allowed to stand on its own? To an outsider and a generalist, the Mānasollāsa is inaccessible as a reference work, since the seemingly important practical discussions are tucked into other sections.

How, then, was the text supposed to be utilized? We must work to unravel the logic in elevating certain activities and obscuring (hiding) others.

The answer has something to do with the way the Mānasollāsa presents its overall project. This is a work that was written in a court and deals with the people and activities around a royal court. At the end of every chapter, the text is emphatic in stating that it was written by the king himself. Some sections are specifically aimed at would-be kings, some are aimed at those who operate around (and come into contact with) the king, and some seem to present universal ethics and regulations..

But though the central organizing principle of the Mānasollāsa is kingship, the image of kingship it presents is rather odd: when Someśvara claims that avoiding untruth is the path to obtaining kingship, are we supposed to take him seriously? Why is there such a large difference between how power-acquisition is presented in the Mānasollāsa and other Indian texts? (Someśvara presents a startlingly different picture of power in his fragmentary prose work about his father’s ascendence.)

Was Someśvara dumb? (No.) Was Someśvara living in some type of bizzaro-world that didn’t obey the political assumptions of our modern world? (No! While his world was different than ours, we cannot say that it was that radically different. He too was living in the Kali Yuga.) Was Someśvara living in a utopianly stable time for the Chalukyas, where kingship may really have passed to the most truthful? (No! Someśvara the Second was killed by Someśvara III’s father in his ascent to power.) Instead of any of these solutions, we must view the programmatic reason for obscuring the difference between theory and practice.

In his essay “The Incense Trees in the Lands of Emeralds,” James McHugh argues convincingly but briefly that the Mānasollāsa is arranged according to the trivarga, the three categories of human pursuits— dharma (ethical behavior and religious obligations), artha (politics and wealth), and kāma (pleasure). The implication is that too attain kingship one must act dharma, to stabilize a kingdom one must act with artha, and to enjoy a kingdom one must act with kāma, and indeed, most of the work is devoted to various types of kāma.

The text revels in aesthetic delights, but to shield the king (and the reader!) from lust (or the accusation of lust…), it reassures us that the king must pass through the stages of dharma and artha before ethically experiencing pleasure.

There is a sort of leading up that must occur before either the king or the reader can encounter pleasure. And if each section leads up to the next one, within each section, each subsection leads into the next. The “enjoyment of the court” begins in the middle of the text (51/100 sections). Standing in the middle of the text (51/100 sections) is the enjoyment of the court. This is the pivot of the text. Once the layout of the palace is described, we are taken through the king’s daily routine. He showers, puts on his shoes, freshens his breath, puts on moisturizer, gets dressed, sets up the court, and finally holds court, putting his decorated and symbol-laden body on display for foreign dignitaries and local nobles. Having held court, having presented himself as the dharmic and arthic king with exterior signs of kāma, he goes about the business that really interests him:

1299cd. Having caused them to go to their own palace, the king who resembles Indra may enter his private play room (keliketana).

1300ab. Playing with those aforementioned women, he may become pleased.

The text is processional. The reader progresses until he (my use of this gendered pronoun is intentional) too may responsibly engage in the pursuit of pleasure. The sections on dharma seem somewhat out-of-place and haphazard. This is not a true Dharmaśāstra: the section that claims to be about how to properly worship the gods (1.12) is really about how to cast an image of a god out of metal. The sections that seem to prescribe normative ethical behavior are brief and nothing more than glosses.

Most sections of the Mānasollāsa tackle scientific knowledge, the mechanics of civilization. They deal with the mechanics for how to produce or use a product of civilization. But these are not clear-cut instructions. They very meticulously list the ingredients involved in mechanical production, but the production itself is obscured. Attempting to make the clothes described by the Mānasollāsa would be like attempting to make Coca-Cola from the ingredients listed on the back of the label.

Rather than being a set of instructions, these are a set of guidelines a highly-trained artistic class can use. It standardizes the materials one is allowed to use in and around the court while naming the products that are allowed to be produced in the king’s presence. It is as much an attempt at prescribing proper behavior as it is one of describing the actual state of affairs.

The one person who unites all of the disparate elements in the Mānasollāsa is the king (in this case a very specific king, the one claiming authorship). The king standardizes knowledge. But what qualifies the king for such a task? But why should we trust him?

If the king organizes the Mānasollāsa, he is also organized by it. His kingship is defined by the way he experiences and organizes the world around him. It is only once he has passed through the earlier sections that he can talk about the later ones. The first major section sets negative limits for the king, while the third section sets positive limits. Only once we are told what food and women a king should avoid (in the first section) can we go on (to the third and later sections) to learn how to win women, enjoy food, and make children. The presumed universal ethic from earlier has transformed: the king has integrated the learning of the earlier sections and now can engage in the pleasures of the later sections with authority.

While today’s encyclopedia can be safely opened to any page, an encyclopedia like the Mānasollāsa gains its authority from the order of its arrangement. Any act of translation must grapple with the complexities of its system of organization and come to understand them on their own terms. If we simply laugh at the oddness of it and use it as an opportunity to critique the systems of power and knowledge of the modern world the text will become mute and greet us with an icy stare.

The Mānasollāsa can be used by the modern reader for many different purposes. If she is interested in a specific topic, the Mānasollāsa can be read out of order. If he wants to get a general sense of trading patterns, or botanical interactions, there are quite a few sections of interest.

But there is also value in reading the encyclopedia as a whole and trying to come to grips with the system of knowledge that produced it. When we struggle with the way other people attempt to organize their worlds as they do so, we can gain an understanding of their world that simply reading texts that take such a system for granted wouldn’t provide. And along the way, the reader will come across some startling and interesting individual observations on life in pre-modern India.

****

Eric M. Gurevitch is a New York Jew currently residing in Mysore, where he teaches English at a Catholic school and studies Sanskrit texts on Hindu kingship and grammar. One day he hopes to be less confused. He often tweets at @EMGurevitch and occasionally blogs at pilesofbricksinindia.tumblr.com