When last we left off (read part I here!), I was discussing an imagined translation of an ordering system devised by a (fictitious) king of Siam in the mind of the (very real) W. Somerset Maugham. This time, I will jump to a different author.

Jorge Luis Borges, like Maugham, takes us once again to a land East of Eden, more precisely, somewhere East of Suez (where the best is like the worst, where there aren’t no Ten Commandments). In his essay “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins,” Borges introduces us to “a certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled ‘Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge’” that was discussed by one “doctor Franz Kuhn.” Borges writes:

In its remote pages it is written that the animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.

I am unsure where I first came across this passage. It may have been in Gallagher and Greenblatt’s book Practicing New Historicism, but alas, that book has since flown out of my immediate possession. If the list in fact is in Practicing New Historicism, Gallagher and Greenblatt almost certainly came across it from reading the introduction to Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things, where Foucault describes his uncontrollable laughter upon first reading the list, which had broken his conception of Western order.

That laughter is that uncontrollable laughter one encounters upon coming across something seemingly familiar, yet startlingly different. It is triggered by the experience of the heterogeneous that Foucault almost certainly read about in Georges Bataille’s essay “The Use Value of D.A.F. Sade.” Bataille writes:

As soon as the effort at rational comprehension ends in contradiction, the practice of intellectual scatology requires the excretion of inassimilable elements, which is another way of stating vulgarly that a burst of laughter is the only imaginable and definitively terminal result—and not the means—of philosophical speculation.

(All we can do is laugh and expel our confusion from our body!).

For Foucault, the Chinese Encyclopedia acts as a “‘real-life example’” of an odd-looking system confounding our conceptions of order. There appears to be a higher principle arranging the list, but we cannot quite put our finger on it. The Chinese mind, like ours, futilely attempts to order the universe: still, we cannot quite make out the logic that drives it.

In Borges’ original narrative, the list does not stand alone: it is surrounded by two other systems of ordering—proceeded by a fully-logical language developed by the utopian thinker John Wilkins in which every object in the world is named according to the part it plays in its system of ordering, then followed by the ordering system of The Bibliographic Institute of Brussels. Mediating these two categories—one whose contents are organized by higher principles and the one whose higher principles are organized by its contents—is Borges’ (invented) Chinese encyclopedia.

For Foucault, the Chinese encyclopedia is the second term in a binary system. It challenges the hegemony of what was assumed to be the lone logical organization principle of the universe. As such, it is wholly other; it is unapproachable. For Borges, though, the list mediates a triad. It allows us to triangulate, to navigate, between two different organizing systems that can exist simultaneously in our heads. It permits the variation in the concomitant to become visible by presenting something that is both like and unlike each of our multiple interpretations of the universe. It organizes our organization principles.

Borges seems to be well aware of the un-respected place (so-called) Eastern thought falls in European ordering systems. The short selection of the call catalogue of the Bibliographic Institute of Brussels he gives directly after his discussion of Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge

has divided the universe into 1000 subdivisions, from which number 262 is the pope; number 282, the Roman Catholic Church; 263, the Day of the Lord; 268 Sunday schools; 298, Mormonism; and number 294, Brahmanism, Buddhism, Shintoism and Taoism.

The massive thought systems of Asia are on par with the history of Sunday in the Christian Church!

What is it that renders the categories of animals in The Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge (aside from its nonexistence) absurd? It is the act of translation that has, once and for all, rendered the list laughable. Little markers restrained within brackets, the letters of the roman alphabet that guide the reader through the strange Chinese categories, make the list meaningless.

We are not presented with the original list (well, there never was an original list, but we are supposed to assume that we are given a simulacrum of the Chinese). Rather, we are presented with a decontextualized list made to fit among a different numbering system. Like the daughters of the king of Siam who end with September, Borges’ list of animals only makes it up to the letter “n.” There is an air of incompleteness about the list, which the categories “(h) included in the present classification” and “(l) et cetera” only serve to reinforce.

The list is a recursive mess of incomplete revisions—something dreamed up by a woeful Eastern king beholden to tradition only to be slightly revised when confronted with the confusion of reality. But the use-value of any list depends on the people using it. In drafting an order, the audience is of primary concern. And while we often assume that an encyclopedia is supposed to be a general summation of everything, in practice that is not the case. Most modern encyclopedias are not supposed to describe everybody’s world. Not every encyclopedia is Britannica. And from the small sample given from the fictional Chinese encyclopedia, I would extrapolate that any larger work it would exist in would be a specialized encyclopedia, not one that adhered to the Diderotian ideal of representing everything.

The section of text is sparse, but there are a few clues we are given that can help us reconstruct greater hypothetical encyclopedia… The work is generically called Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge. It is aspirational. The text exists outside of the normal world of things. It is not a farmer’s almanac—the first item, “(a) belonging to the emperor,” and “(k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush,” would be of little use in the knowledge system of an agricultural worker. It is not medical dictionary, for what use would a doctor have with animals that are “(b) embalmed” or “(n) that from a long way off look like flies”? It is not a list designed for a tax collector, because one cannot exact taxes from “(e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs.” The Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge is a likely specialized encyclopedia for artists in a royal court.

…Of course this is all nonsense. In reality, the list and its encyclopedia was constructed for a Western frame of knowledge, and the list both challenges and supports the hegemony of that system. Maugham designs his Siamese king to make us laugh at a man who thinks he can fully categorize his children; Borges designs his encyclopedia to make us laugh at people who think they can organize the world.

By laughing at others, we criticize ourselves. This is where the danger lies—if we are to successfully grapple with ordering, we must understand it on its own terms. An encyclopedia already performs one dangerous act of translation: it translates the language of things into that of man, and we have to be very careful when we translate this translation. If we keep on renaming and retranslating other systems of knowledge to explain the world we live in, they may become embittered like the king of Siam’s daughters in the Maugham story or worse—they’ll grow silent like Nature does in the epigraph from Benjamin that started the first post off.

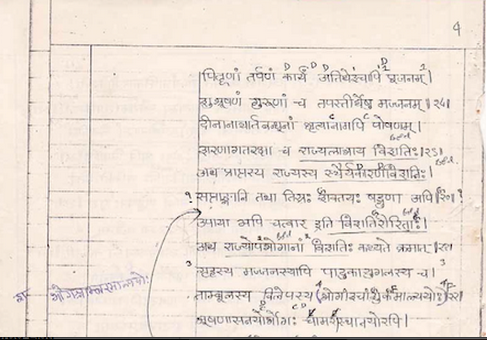

Up next: I will discuss a very real Asian encyclopedia, the Mānasollāsa (Delight of the Mind).