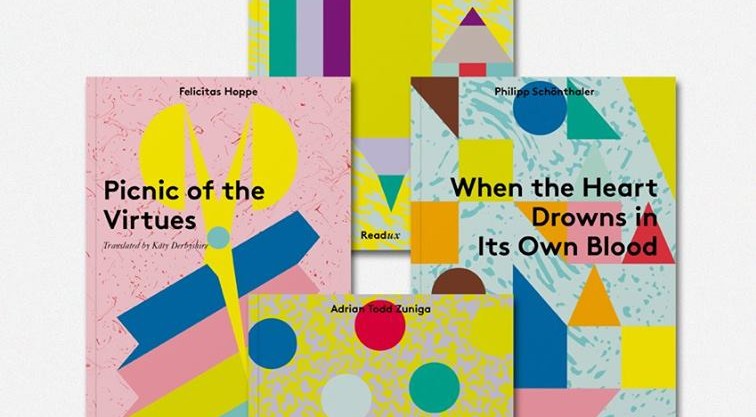

Last night, at an intimate jazz bar hidden away on one of Berlin’s many courtyards, Readux books presented its gorgeous second set of books. Hardly larger than the next generation of cell phones, these little books are designed for brief escapes, mini-breathers away from your screen (although they’re of course also available as ebooks, who are we kidding?).

There were readings, short discussions, and delicious and plentiful vodka tonics, spring was very much in the air—it’s no coincidence that these books do well on lunch-break benches underneath Berlin’s tender first blossomings.

The first set of four Readux books, published last fall, featured fiction translated from the Swedish (Fantasy by Malte Persson, translated by Saskia Vogel) and the German (The Marvel of Biographical Bookkeeping by Francis Nenik, inventively translated by Asymptote contributor Katy Derbyshire), as well as twin looks at Berlin (one through Franz Hessel’s writing about the city in 1929, translated by Readux’ publisher and fellow contributor to this journal Amanda DeMarco, and the other through Gideon Lewis-Kraus’ original new essay about his compulsion to write about the hipster-attracting metropolis it has now become).

The second set, two of which were officially launched last night, are all short works of fiction of about 30 pages long. In one, Felicitas Hoppe, a German writer whose amassing of numerous awards has refreshingly in no way tampered with her inventivity and playfulness, tells five sinisterly funny fairy tales entirely worthy of her stature (also making it clear that she indeed is perfectly suited to be the official translator of Dr. Seuss in Germany). Translated by Katy Derbyshire, they retain the originals’ sly wit, even making the author herself laugh at last night’s reading.

When the Heart Drowns in Its Own Blood by Philipp Schönthaler, on the other hand, though just as sly, makes the reader work a little harder, as it tells the story of one man’s quest to dive deeper than anyone has done before. What at first seems like a magazine profile of the athlete, capturing soundbites as he trains for his big dive and navigates the media circus growing around him, sneakily turns into something more philosophical and psychological, his physiological exertions matched by introspective diversions.

After his translator Amanda DeMarco read an excerpt from the book, I had the great pleasure of conducting a brief Q&A with Schönthaler about his writing and his inspirations. We learned that he had first come across the idea of using an extreme athlete as a focus for his fiction when studying the writings of mountaineers for his PhD work, and the stories in his debut collection, Life Opens Upward (which won the 2013 Clemens Brentano Prize) all in one way or another feature athletes whose work at the edges of human capability makes them lightning rods for philosophical, economical, and even religious queries that affect us all. No surprise then that DeMarco, when translating his stories uncovered unmarked quotations from Goethe and Descartes, even Heidegger, all of which she carefully reburied in the English translation.

Developing his fiction alongside his essayistic work allows Schönthaler to tighten or release the reins of his imaginative and scholarly impulses. His next project? An essay on survivalist culture in Europe, another group of people not shying away from the threshold of humanity. Like athletes preparing for their best performance, these survivalists are preparing for the worst, both narrowing their focus on physical survival and in the process, perhaps, reaching some sort of spiritual purification. Below is a short email interview I conducted with him about these matters and his stories earlier this week.

Florian Duijsens: As I believe this was one of the first times you were being translated in English, I was wondering what the experience of being translated was like, did it force you to look at your own work differently?

Philipp Schönthaler: One of the short stories from my collection had been translated in English before. Nonetheless, the experience of being translated is still new and what this means is only just slowly setting in. And indeed, it does provoke a different look at my own writing. The precondition is, of course, that I feel fairly comfortable with reading in English and have a certain idea or grasp of North American culture (which would be my first reference here before the UK, the reason for this probably being that I spent more time there, but it is also Amanda DeMarco’s background, who did the translation). This allows me to read my own writing in the English translation with this strange feeling of a great familiarity and a certain estrangement at the same time, which I really enjoyed and still find very productive. For example, reading the translation, I automatically look for different references or muse about parallels to authors that I certainly did not have in mind when I was writing the text originally.

Another experience was that I felt very tempted to make some alterations to the original after we discussed some issues of the text during the translation process. Since writing is in large parts a fairly lonesome business, I find it very attractive that with the translator there is someone else coming in, participating in and even altering my work. That this also leaves a lot of room for frustration is obvious, but in this regard I guess it has been a very lucky and satisfying start for me.

Now that these small slivers of your work are available in English, you’ve officially entered a (geographically) larger arena of literature. Are there any non-German authors whose work you admire, or who’ve influenced your own writing?

Yes, definitely. I guess my reading in the last couple of years has been focused mainly on a European corpus of literature and philosophy, and in addition to that, of course, also on American literature. I think that this is also the context that ‘naturally’ directs my writing. After shunning German literature for many years, I have really been quite taken by it in the last few years, so I have been trying to catch up. As became clear in recent German newspaper debates about the perceived weakness of current contemporary German literature, critics here seem to suffer from a kind of inferiority complex, believing that German literature does not really play well in the big arena of world literature—one point being that there are hardly any authors, established ones as well as younger ones (with exceptions such as Daniel Kehlmann or Saša Stanišić), who write books that become international bestsellers. I don’t worry about this ‘bestseller’ yardstick, and would rather stick with or name authors who don’t have this international (or even national) success, writers such as Thomas Meinecke, Andreas Neumeister and Kathrin Röggla, or, to name writers of my generation, Kevin Vennemann and Jörg Albrecht.

Yet, having said this, focusing only on this national context would feel much too confined and I would never want to restrict myself to it. I hesitate to give single names, since the list of non-German authors would be too long, yet two American authors I have been reading lately with great pleasure are Robert Coover and David Markson.

As someone who has worked in academia and written both shorter and longer works of fiction, how do you see the boundaries between essay and story, between philosophy and narrative?

I am a fan of Jacques Derrida, so theoretically I would agree with the premises of deconstruction that the boundaries are inherently instable. Nonetheless, I still find the differentiations useful. As for my own writing, I have always started off with a clear idea and style of writing in mind that unquestionably differed depending on whether I was working on an essay or a piece of prose. I appreciate the first because it teaches me to think more stringently, and I turn to prose because it allows me to move more freely.

With athletes and physical feats being the topics of both these translated pieces, I was immediately reminded of David Foster Wallace’s writing on sports. In one essay, he wrote that “Great athletes usually turn out to be stunningly inarticulate about just those qualities and experiences that constitute their fascination” and “The real secret behind top athletes’ genius, then, may be as esoteric and obvious and dull and profound as silence itself”. In short, he believed that what goes through a great player’s mind may be nothing at all. Are these stories a way for you to plumb these depths of athleticism, scale these heights of skill in their place?

In regard to sports, I am indeed particularly curious about how some of the stories work for a North American audience. Whereas sports is a major theme in American literature, in German literature it is virtually non-existent. This, of course, has to do with the different roles sports play within the different cultures, most importantly probably the phenomenon of college sports, which we don’t have in Germany and which is therefore completely missing in German literature as well. I can hardly think of any major German novel where an athlete would be a main protagonist or sports would be central to the plot. Wallace definitely was one source of reference. At the same time, however, I am approaching sports from a different and much more abstract angle. Perhaps, this could not have been any other way, taking into account that the athlete doesn’t exist as literary figure within German literature.

What first sparked my interest was the metaphorical relation between sports and what sometimes is referred to as the neoliberal society, a society of competition. This seemed to work on a discursive level, but also in terms of form. Since the athletic self easily translates into a performative self, this allowed me to develop a certain style of writing which takes up this performative quality on a formal level. In the collection of short stories, I play with both strands, thematic as well as formal issues and correspondences that spring from this metaphoric relation between sports and society as both being structured through competition.

To give one example: In “The Hay Smells Different to the Lovers Than to the Horses,” the story which appeared in the last issue of Asymptote, what first attracted me was the phenomenon of superstition, which is not uncommon among professional athletes. I was curious about the type of rationality that is at work here, i.e. the threshold at which point the utmost degree of self-control and rationality that athletes need in order to be able to excel at a specific point in time tips over or—to put it more strongly—necessarily produces forms of irrationality.

However, I do want to answer your question more directly: I would probably agree with Wallace’s description of the athletic genius. At the same time, in order to point to the structural problem or scenario that fascinates me most, I would rephrase his description as follows: it is a precondition for the athlete that ‘nothing at all goes on in his mind’, since every form of introspection or even doubt would threaten their ability to reproduce their highest performance at will. What interests me is this structural phenomenon of professional sports as a cultural practice, perhaps you could even speak of a theory of action that comes into play here, revolving around a model of the individual that is focused on functioning absolutely efficiently and successfully.

On the one hand, my presupposition regarding sports would be that this is also at work in other spheres of society that are based on principles of competition and success. On the other hand, there is also a more or less natural point of entry for literature—if you take literature to be a practice that doesn’t suffer from the same compulsion to act or show measurable results. Literature can open up a space that allows us to raise questions and doubts, not just in general, but also in a specific sense that shows that doubt or failure, as well as the inability to act, are intrinsic moments within the logic of competition and success that are otherwise often invisible.

***

Read Philipp Schönthaler in Asymptote here!

***