On January 22, translator Lucas Klein posted Translation & Translation Studies as a Social Movement, responding to a LARB review of Mo Yan’s Sandlewood Death that only fleetingly mentioned its translator, Howard Goldblatt. The post went viral, and rightly so: Xiao Jiwei’s unfortunate review was symptomatic of the predominant tendency to make translators invisible—a tendency that hurts not only the translators themselves, Klein argues, but the quality of translations and literary criticism as a whole. The solution? Translators must organize—demanding respect commensurate with their role in shaping the world. An interview with Asymptote.

English-language markets already publish notoriously pitiful quantities of translation. To add insult to injury, you argue, translators aren’t being adequately recognized for their work. Where—and how—are translators being made invisible in these markets?

A number of years ago an acquaintance of mine was reading Love in the Time of Cholera, and she remarked to me how relieved she was to be reading something Gabriel García Márquez had written in English. Not only did she have no notion that Edith Grossman was responsible for the quality of the writing, she also made the mental excuse for herself that such quality of writing wouldn’t have been possible in a translation.

Now Edith Grossman is one of the most respected and renowned literary translators working into English; the cover of her translation of Don Quixote displays her name prominently under Miguel de Cervantes’s. But that reveals the invisibility most of the rest of us operate under. It’s rare for translators to have our names on the covers of our books. There’s no real reason for this; actors get their names on billboards for the plays and movies they’re in—why not translators?

As I understand it, the fact that we have “movie stars” developed out of a need for movie studios to mitigate risk. Basically, there’s no way for us to tell if a movie’s any good before we see it, but we’ll pay for anything our favorite star is in. The story goes that translators get reduced to invisibility because of how publishers want to mitigate risk—as in, they see publishing translation as even more of a risk than publishing anything else, even though translations also come with sales figures in other languages—but it’s conceivable that it could work the same way as it does with movie stars. I know I’ve bought books by authors and poets I’ve never heard of because I trust the taste and style of Gregory Rabassa, Suzanne Jill Levine, Eliot Weinberger, Rosmarie Waldrop, Clayton Eshleman, John Nathan, Susan Bernofsky…

The complaint that translators aren’t given due consideration isn’t exactly new. Why do these problems persist?

On the one hand, I think a lot of translators believed that we had made progress in raising the overall profile of translation and translators. We as translators have been pretty vocal about this, and as a result, a lot of reviews do mention translators’ names—though by and large we’re still in the ghetto of one- or two-word appraisals (expertly translated by, seamlessly translated by, awkwardly translated by, etc).

So there’s been something of a rebirth in translation and translation-related activism, which Eliot Weinberger attributes to opposition to Bush policies and the War on Terror. “In the din of the bulldozers of the Pax Americana,” he wrote, “some want to have small conversations with the rest of the world. In this sense, the junta ruling under the name of George W. Bush has been very good for American literature.” In some ways, this seems to have continued under Obama: Chad Post of Open Letter Books, which publishes only literature in translation, announced that 2013 was the first year in which he could count over 500 books of never-before-translated fiction and poetry in his American Translation Database.

This is why it’s such a surprise to see a recent surge, if that’s the right word for it, of reviews conspicuously not mentioning the translator. Just came across another one: Emily Cooke’s review in the New Yorker of Anne Appel’s translation of The Art of Joy, by Goliarda Sapienza. Cooke even talks about “translation” in her review, but not about this specific translator or this specific translation, since evidently the fact of translation is important enough to mention, but the individual or individuals responsible for that fact are irrelevant. I think of it as a counter-attack by the ideologically conservative—those who think translators are like children who should be heard but not seen.

On one hand, it seems as if there has never been a better time in translation—the Internet means the world’s languages are at our fingertips, and there hasn’t been an easier or more efficient way of literary distribution (Asymptote and Words Without Borders, for example, are translation mainstays and could not exist without the Internet). Does the Internet complicate—or improve—the situation for translators at all?

Certainly the Internet complicates the situation for translators. While in some ways the distribution and dissemination of our work, and of international literature, has improved, the matter of payment and proper attention is very complicated. Buzzfeed, for instance, has decided that it wants to internationalize, but not if it means paying translators to be part of the process. So they’ve contracted with Duolingo to have language-learners, unpaid and presumably inexperienced, translate Buzzfeed content as part of their language-learning process. I try to avoid clicking onto Buzzfeed pages because of this, by the way.

Then there’s the issue of what the Internet does to readership communities. In lots of ways the Internet can expand readership communities, so if you’re interested in experimental poetry or science fiction you have exponentially more people around to be in dialogue with and introduce you to more to read next. It’s great that I know there are 500 new books of poetry and prose in translation, for instance—that’s certainly more than I can read in a long time. But the Internet also contributes to reifying and raising the walls between readership communities, too. This is something I’m very familiar with as someone who follows contemporary American poetry, or who’s part of that community. Gary Snyder is probably the last avant-gardist American poet who can have a reading that will attract a large audience of non-poets. Maybe John Ashbery. Both translators, incidentally.

So the Internet may make it harder for people not in the literary translation community—people outside of our echo-chamber and in their own echo-chambers—to know about literary translation and the things we find important. Readers of The New Yorker may be different individuals from readers of Asymptote, so if Asymptote draws attention to the translator but The New Yorker is still keeping the translator’s name out of reviews, are we expanding our readership and our program?

What do you mean, exactly, with the phrase “translation and translation studies as a social movement?” “Social movement” for whom?

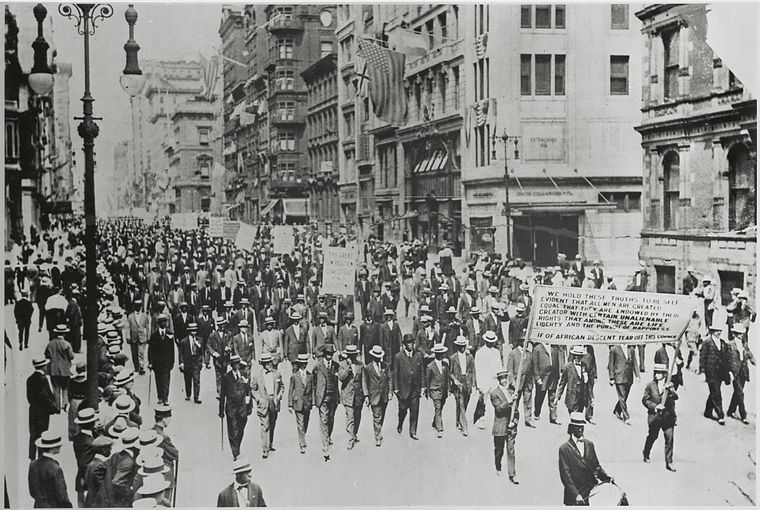

I mean a movement to change society. All society, but particularly the society of English-speaking countries. I think of social movements for civil rights, from feminism to anti-racism to gay rights to immigrants’ rights, which have pretty clear beginnings but no clear endpoints. We certainly haven’t eradicated racism or sexism in our societies, but things are better in these areas than they were a few decades ago, and more people have an awareness of how such issue are at work and at play in their lives. I see translation as being a part of such larger social movements, particularly as related to immigrant rights—we’re trying to increase diversity in world we live in and the world we read in—but also to other struggles such as workers’ rights, as well.

My own awareness of social movements has to do with my experience in trade union organizing. The union I organized for, UNITE HERE, practiced what’s called social movement unionism, in which negotiating contracts ensuring security and benefits for its members is important, of course, but cannot be done absent organizing ties with the community and broader fights for social justice, human rights, and democracy. Now, it’s hard to imagine literary translators organizing in traditional ways for better work conditions, but I think it’s very easy to imagine a broad-based conversation that emerges with society understanding translation as something that needs to be understood and respected as part of a larger movement for change in favor of democracy, egalitarianism, and pluralism. Even when the literature we translate doesn’t necessarily argue for or uphold any of those values as such.

Who, besides the translators themselves, stands to benefit from reversing translators’ invisibilisation?

The great thing about a social movement is that it’s hard to imagine who doesn’t benefit. I mean, there have been men who evidently find themselves inconvenienced by feminism, but I’m more compelled by arguments that men benefit from feminism, that companies benefit from giving women and men equal pay for equal work. I’m sure at a certain level publishers will resist drawing more attention to the translator—as I noted above, they tend to exhibit pretty risk-averse behavior on this issue—but if they see translation becoming more and more acknowledged and becoming something people by books for, they’ll probably come around.

As for who else benefits, if we imagine a translation-based social movement as contributing to the growth of democracy, egalitarianism, and pluralism, then I think everyone benefits. Sometimes I translate millennium-old poetry written by and for the literate minority of the Chinese imperial court; that’s not directly political. The reason I said that translation can be part of positive change for democracy, egalitarianism, and pluralism even when we’re not translating works by democracy activists and egalitarians is that these concepts themselves are based on a broader conversation, a conversation in which you don’t have to be on board to play a role.

But I think in particular we can narrate translation as most directly related to struggles for immigrant rights, on the hinge that we’re advocating for diversity within the field of what our society reads just as through their presence immigrants improve societies that would be pretty monolithic without them, and that we’re telling stories that inform the worlds the immigrants emigrate from.

You mentioned in the blog that translators’ unionization is unfortunately felony-worthy in the United States—without risking a prison stint, what sorts of things should translators and those invested in the quality of translations be doing to better the situation as it stands?

The first point I should make is that translators can join, I believe, the National Writers Union (NWU), which is Local 1981 of the UAW, or United Auto Workers. I don’t know much about what kinds of immediate benefits it can secure for any individual literary translator working with a publishing house, but it’s there, and I for one welcome the opportunity to be organized by a member.

In terms of specifics, I recommend all literary translators negotiate in their contracts to have their names on the cover, to get an advance on royalties instead of a flat fee, and to have right of first refusal if the publisher wants to publish another book by the same author. The presses I’ve worked with so far (New Directions, Black Widow Press, and Zephyr Press), have all been very good about this, though I hadn’t thought of the right of first refusal issue the last time I negotiated a contract. These are also small presses, and as I understand it, it’s the larger presses that are more obstinate about how they treat translators. Also, a friend tells me she’s got it in her contracts that her name must be mentioned on all publicity produced by the publishing house. That should help in getting reviews to mention her, as well.

Also, anyone interested in improving the quality of translations should write reviews—I’m talking about reviewing for venues like newspapers, magazines, and literary journals, but blogs and GoodReads would certainly help, too—that devote attention to the translation and how it shapes the overall success or failure of the work in question. It’s generally unpaid or lowly paid work, but it contributes to the community and the community’s conversation about the writing that unifies it, so it’s valuable that way. I’ve published dozens of reviews, almost never for pay, but I feel like I’ve both learned a lot and explained a lot in the process.

_______

Interview conducted by Patty Nash.