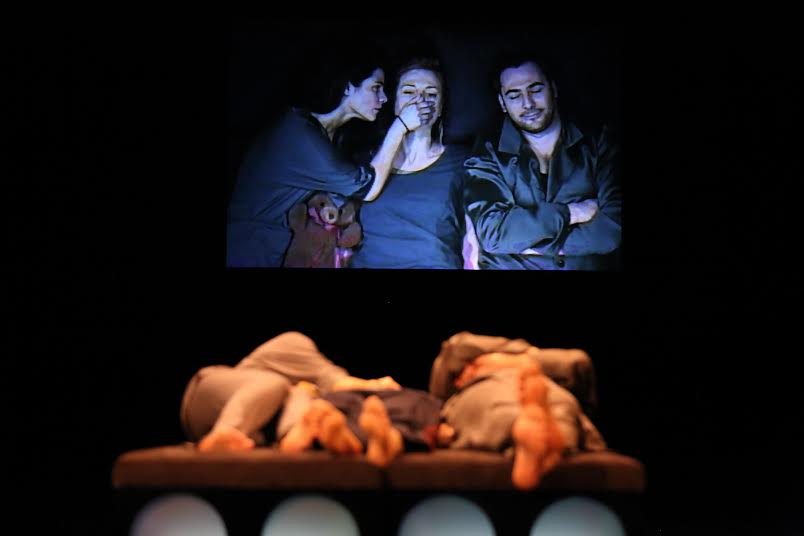

This year’s Croatian Theatre Showcase, held from November 28 to December 1 in Zagreb, was the first such revue since Croatia joined the European Union last July. The plays represented in the showcase were not simply the most popular or highest-grossing shows of the year; they all shared a certain attitude, a social awareness, a desire to, as the organizers stated, “speak out about the time and place in which they were created.“ Fine Dead Girls (directed by Dalibor Matanić) deals with the issue of our society’s attitude towards homosexuality, Hermaphrodites of the Soul (choreographed by Žak Valenta) and A Barren Woman (directed by Magdalena Lupi Alvir), each in its own way, tackle the problem of gender roles, while Yellow Line (directed by Ivica Buljan) speaks out about our uncertainties and misgivings about the European community we recently joined. Coupled with the fact that all of the shows were translated and subtitled in English, it could be said that the aim of the Showcase was to represent not only Croatian theatre, but the current state of Croatian society in general, to foreign viewers. Intrigued by this concept, I sat down with theatrologist and dramaturge Matko Botić, one of the organizers of this event, to chat about the Showcase, the idea behind it, the issues arising from translating theatrical texts, and the state of Croatian theatre in general.

First, I’d like to ask you about the Croatian Theatre Showcase, how long has this been going on, what’s the concept behind it?

It is a project of the Croatian Centre of the International Theatre Institute, an international organization dedicated to theatre in the broadest sense, promoting and studying the various effects of theatre. The Croatian center is among the strongest ones in Europe, and this Showcase is part of the Centre’s varied activities. It is based on the experience of foreign theatrical festivals: there is a tradition of showcases accompanying the main program of major theatrical festivals. Professionals who are in any way interested in a country’s theatrical output – producers, translators – are invited to see, in a couple of days, sublimed and condensed, the highlights of the year’s theatrical production, which enables these plays to appear in other festivals. That’s the guiding principle: to gather the people who can provide a play with a new life, and show these people the best of the year’s work. We have a network of producers and professionals who we know can help make that extra step in the promotion of a show.

How long has the Center been organizing these Showcases?

This has been the ninth year.

So, next year we will have an anniversary festival.

Yes, but it isn’t a festival in the classic sense. We simply send out invites to the theatres which house plays we consider to be worthy of showing, and arrange for seats and subtitles to be made available on a certain evening. This is the case with plays which would have been on anyway, but there is also the option, as with two plays in this year’s Showcase, to find interesting performances from the extra-institutional sector which do not have permanent venues. In those cases – like with Hermaphrodites of the Soul by Žak Valenta and A Barren Woman – to stage a play especially for the Showcase, at a venue we provide.

Since the target audience of the Showcase is this network of foreign collaborators and producers, you need to provide a translation for them, so that they can see both the verbal and the performance side of the story. What is your opinion on subtitles in theatre in general, what effect do they have on the perception of a play?

Subtitles in theatre are definitely a necessary evil. During my visits to foreign festivals, if I don’t know the language, I depend on the subtitles, so they are very important. But I still see, even if I don’t understand the language, that the subtitles are visually detached from the action onstage…

Unlike on television, where they’re part of the picture…

I think this is a classic question of focalization. In theatre, you have a multi-perspective possibility of choosing what to focus on, and in television you are forced to see the director’s perspective: he dictates what you see. It’s still a problem in television and cinema, you do need to focus a part of your brain on the subtitles; but in theatre it’s an additional problem. As soon as a subtitle is provided, you are somewhat forced to focus on the plot and dialogue. So you spend a lot of time looking at the subtitle, and it’s always in some sort of inadequate position; it’s either to the left, or to the right, or too high up…

And that’s not standardized.

Nor can it be, since every theatre hall is different. In my experience, the worst option is to have the subtitles to the left or the right, it is very distracting and it hinders the audience’s ability to follow the plot. There are several directors who expressly forbid subtitles. When Árpád Schilling brought his excellent Hungarian production of The Seagull to Rijeka, he insisted that every member of the audience should have headphones with simultaneous interpreters translating the actors’ words, to prevent the distraction caused by subtitles. But this too can be a sort of distraction, on the aural level. And that’s not the only example: András Urbán interestingly enough, both of these directors are Hungarian – did a show, in Serbian, which contained some Hungarian words, and these were played to the audience over headphones. These examples point to the conclusion that subtitles are not something that comes naturally to theatrical performances.

But then there’s the issue of translating and/or subtitling plays which are very firmly rooted in a particular culture. For example, the Showcase included a production of Fine Dead Girls, a play based heavily on specific events in and elements of our culture, which our audiences find instantly recognizable; war veterans, Thompson… and Arsen Dedić. Are subtitles detrimental here as well, or can they help the play maintain that otherness of Croatian culture in relation to our shared European culture? Could the fact the actors are talking in Croatian about elements of Croatian culture and history, mediated through subtitles, help in reaching other audiences in a way that an adaptation or translated staging, with actors speaking in English, couldn’t achieve?

Absolutely, that’s why I call subtitles a necessary evil. The very nature of subtitling a theatre performance rests on the desire to provide a foreign audience with an authentic experience of the play, as much as it is possible in this mediated and indirect way. If the subtitles are done skillfully, with a familiarity of both the source and the target languages, they can be used to provide the audience with as much local flair as possible. That is what subtitles are supposed to do. I generally prefer to see a play performed as closely as possible to the way the author envisioned it, but there are cases where adaptations, in language or setting, were performed so expertly that the entire play acquired some brand new qualities.

Can you provide an example of that?

Jagoš Marković staged an adaptation of Eduardo de Fillipo’s Filumena Marturano, localized into the setting

of Croatia’s Kvarner region. The playful Italian flair of the original was transposed into something recognizable to the audience; it was very successful, perhaps even better than had they stuck to the original. On the other hand, I’ve worked on an adaptation of Feydau into the context of urban Rijeka, and that didn’t work at all. Feydau’s vaudevillian mathematics, locally adapted, looked like a B-level comedy, so I don’t think we can establish a general rule. However, it’s interesting to note that almost all Serbian plays performed in Croatia were adapted, at least linguistically, to a standard variety of Croatian, while almost all Croatian plays are performed in Croatian in Serbia.

That might be a political issue.

Well, yes. It’s definitively interesting that Biljana Srbljanović’s characters speak Croatian in Croatia, while Tena Štivičić’s characters speak in urban Zagreb slang when her plays are performed in Belgrade.

You said that a part of the concept of the Showcase is the idea to provide these plays with a new life, outside the borders of the countries in which they were made. Is the basic idea that the existing ensembles will perform these plays abroad? Or that foreign theatres would stage their own adaptations, their own performances of the showcased plays?

Both. Our Showcase’s target audience consists of both producers and translators. Each of those groups has its own role. Producers and festival selectors look for shows, complete performances, but we’ve had several interesting instances of translators participating in our showcases. For example, Larisa Savelyeva, a translator from Moscow, was introduced through our Showcases to the work of Mate Matišić, and she has already translated five or six of his plays, offering them to Russian theatres where they are now performed. This year she came to see Fine Dead Girls because the well-known Russian director Alexander Ogarev, who has already staged several plays here in the Gavella theatre and in Split, expressed a desire to stage Fine Dead Girls, which is very interesting, since the attitude of the Russian government and culture towards the issue of homosexuality is well known. She will translate the play, but it is unlikely that the political climate will allow it to be staged. That’s one specific example. So, both of these things are welcome: translating theatrical texts that an audience would find interesting, and hosting complete plays on festivals abroad.

With that in mind, what is your opinion on the state of Croatian theatre? How much interest can it draw from foreign audiences?

There are a lot of interesting people and ideas but, like elsewhere in the region, the problem is money. Only the largest institutions get funding. If you want to work at the extra-institutional level, you are faced with the problem of setting up a structure capable of producing anything. On the other hand, the big institutions, especially those in Zagreb, are managed by people who have no desire to make qualitative leaps, but are instead interested in maintaining the status quo. However, the Zagreb Youth Theatre is doing some very interesting things, Nataša Rajković in the &TD Theatre is always trying to find young people who have something new to say, and there are a lot of people trying to create something good outside the institutional framework. Sadly, the state of affairs in the institutional bloc, which receives most of the financing, does not bode all that well.

Thank you for the talk, hope to see you next year!

—

Matko Botić was born in Rijeka in 1980. He lives and works in Zagreb as a theatrologist, dramaturge and musician. He graduated at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Rijeka, majoring in Croatian language and literature, and attained his Ph.D. in literature at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb in 2012. His doctoral thesis was also published under the title Igranje proze, pisanje kazališta (Playing prose, writing theatre) as part of the Croatian Centre of ITI’s Mansioni edition. He collaborates with various directors on projects ranging from theatre and television to radio and film productions, as a dramaturge and musical score composer. He publishes theatrological texts and theatrical reviews, usually in the Kazalište magazine. He collaborates with several theatrical festivals in the region, as selector, guest-critic and panel moderator. He plays the guitar and mandolin in My Buddy Moose, an indie rock band from Rijeka.

Vinko Zgaga was born in Zagreb in 1983. He graduated at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb in 2008, majoring in Anthropology and English Language and Literature. Since 2009 he has been translating and working at the English Department of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, teaching courses in the English language and various translations courses, encompassing topics from scientific and journalistic texts to literary translation and subtitling. Plays he has translated have been staged in several major national theatres, including the Gavella Theatre in Zagreb and the Croatian National Theatres in Osijek and Varaždin.