Reading often fools us into feeling like we’re conversing—the words touch our eyes and yet seem to come in through our ears. It is no wonder that people often feel a bond to their favorite writers, their favorite books. They think of them as friends—that first person voice is talking to me, this story was crafted with me in mind. We extract secret meanings: my definition of blue is not the same as yours (I think of a butterfly my mother captured when I was in elementary school); I render Middle Earth far differently than Peter Jackson. Every book is a Choose Your Own Adventure, that way.

For a special sort of reader, a translator, the words on the page are a kind of dialogue. That dialogue is not between writer and reader, either, but between languages—the translator is an intermediary between scattered cousins, reintroducing them to each other: red, this is rosso; cat, this is gatto.

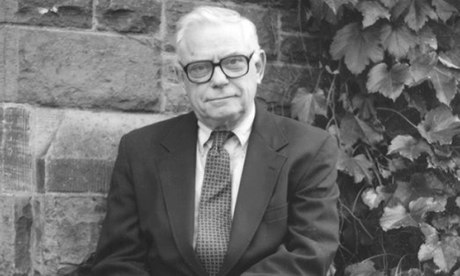

You don’t translate a name, you accent it—give it the native garb so it doesn’t stand out so obviously. I imagine William Weaver dripping with delicious Italian sounds as the young man it described traipsed about the country, picking up new words like ripe fruit dropped from fat trees. I cannot speak so personally about him as some; I never met him, never saw him lecture. Still, I feel a connection, for he was someone who brought me writers I never would have known without his efforts.

Weaver died last week in Rhinebeck, New York. He famously translated dozens of works by modern Italian giants, with voices as diverse and idiosyncratic as Umberto Eco, Primo Levi, and Paolo Pasolini. He was Calvino’s translator, too, and because of him Calvino is one of the writers I revere the most. I feel a special kinship with Invisible Cities— Le città invisibili—because my father recommended it to me. I was around sixteen the first time I read it. I had reached a point where it was usually Dad asking for what to take down from a high shelf. He offered it with a snippet of praise that I wish I remembered. Something about it being a favorite, certainly, and something about it teaching him how to think. About what cities could be, I want to say. I took it to my room, read the front cover and then the back. I didn’t quite understand what was there; the blurb had been provided by Gore Vidal, and concluded: “Of all tasks, describing the contents of a book is the most difficult and in the case of a marvelous invention like Invisible Cities, perfectly irrelevant.” I opened to the back page, expecting some biographical details on the author, and instead found two neat columns of numbers, arranged, I thought, like a code might be. It was my father’s handwriting, unchanged after however long, though I had some inkling because he had written Bethlehem, PA above everything, the site of his college years. I turned to the pages I figured the numbers corresponded to, and so started the book that way, on page 19, reading my father’s favorite cities first.

I have since read that book a half dozen times. I dream of the places, I know my favorites by heart. My copy has but a single line crediting Weaver’s work, a tenth of the size of Calvino’s name. The translator is the friend who introduces you to your future wife, says to you, all starry-eyed, I know someone you’d like. You’re skeptical, because how could anyone know you so well? And then you see her, and then you talk to her, and later, you text your friend, you might be right. And later, you hug him, tearfully, at the reception. You spend your life in love; you spend your life in gratitude.

It is too bad about Babel. I have always thought it would be wonderful to be able to communicate precisely with anyone anywhere. But then I wonder if we could ever fill the voids our language undoubtedly would have, all of us hacking away at the world with the same sounds. How apt a name was Weaver for a man who found the shapes to fill the lacks. Instead of reaching skywards, he taught us to look left, look right, and showed us what we have among us. He let us listen in on places far away, and so expanded our place of comfort.

Photo by Doug Baz, Bard College