A new story by Haruki Murakami was published in the October 28th issue of The New Yorker. The story is called “Samsa in Love” and is translated by Ted Goosen, who often translates Murakami’s Canadian releases. The story concerns someone who wakes up as a man named Gregor Samsa.

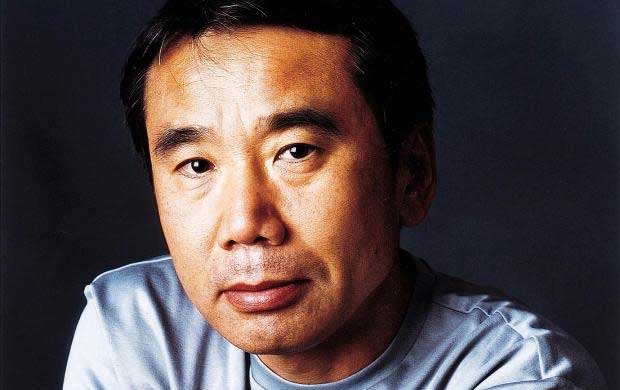

Murakami is an immensely successful writer—a superstar by any measure. His most recent novel is the fastest selling book ever on Amazon Japan, and he has a devoted fan base around the world, one that extends beyond conventional literary circles. This story, for instance, was heralded on Reddit. He is also an accomplished translator. He has translated into Japanese The Great Gatsby and The Catcher in the Rye, among other notable English works. He is a prolific writer, with thirteen novels to date, and nonfiction and short story collections as well. He is Haruki Murakami—you know all this.

Another thing you probably know is Kafka’s Metamorphosis, which to say this story is based on would be technically correct but thoroughly insufficient. This story is that story, though without any of its malice or dread or anguish. That is because this story is that story told in reverse, with a few subtle but significant changes. The first is that Samsa died in Metamorphosis, which is a very difficult process to undo. The second is that Samsa’s family is nowhere to be seen. The third is the presence of a hunchbacked love interest. And the fourth is the treatment of language.

The first three are minor. I suppose it is charming, in a way, that Murakami’s piddling Samsa falls for a girl who reminds him of an insect, but it does not much matter what elements of the plot Murakami chooses to deemphasize in his rendition. However Murakami’s treatment of language, particularly Samsa’s, is what makes the story at all worthwhile. Kafka heavily emphasized Samsa’s inability to communicate with his family; indeed, Samsa’s failure to express himself and to convey his understanding is the greatest tragedy of Metamorphosis. At the end, Samsa dies hoping to lessen the burden he’s brought upon his loved ones—but they show no gratitude, only relief. It is impossible for them to recognize love when it comes from a bug. The absence of audible speech makes Samsa incapable of possessing any humanity.

Murakami rightly makes the reader wait for Samsa’s first words. And he keeps us out of his head, too. Where Kafka rendered Samsa’s thoughts as apart from the author’s own narration, adorning them with quotation marks and utilizing the first person, Murakami’s “Samsa in Love” is told in the third person from the onset and rarely slips. Samsa’s thoughts are spoon fed to us and to Samsa himself at the same time: “Samsa had no idea where he was, or what he should do. All he knew was that he was now a human whose name was Gregor Samsa. And how did he know that? Perhaps someone had whispered it in his ear while he lay sleeping? But who had he been before he became Gregor Samsa? What had he been?” If this were Kafka, these questions would likely be written as: “How do I know that? What was I?” Murakami sees the transition from insect to human as being literally about finding his voice. Later, Murakami writes: “Why hadn’t he been turned into a fish? Or a sunflower? A fish or a sunflower made sense. More sense, anyway, than this human being, Gregor Samsa.” There is a resistance—our hero refuses to be Samsa, refuses to claim the name. He finds this body ugly, poorly designed, fatally flawed.

He starts to satisfy the needs of this self, though—the self represented by the body—and in doing so he starts to use the language one uses when autonomous. He feeds himself and we see the pronoun I for the first time, once and as if it had strayed from another word, still tied to thoughts of fish and sunflowers. His hunger satisfied, he feels cold. Murakami writes: “Yes, he thought again, I must find something to cover my body.” There is an inkling of ownership. He finds some clothes and puts them on. He is doing what a human must, and so he is coming closer to what a human is.

His transformation is accelerated when the hunchbacked woman arrives to fix a lock. I’m not entirely certain why she must be hunchbacked, but it’s Murakami, so she is. She asks if this is the Samsa residence—an indirect way of asking if Samsa is Samsa—and Samsa says his first word—“Yes.” To make sure you didn’t miss how important this was, Murakami has his hunchbacked lady ask again, and this time Samsa says, “I am Gregor Samsa.”

The girl brings with her a veritable deluge of new information. New words: Murakami again highlights the Kafka connection by saying Samsa was particularly confused by God and pray and fuck. She says some vague things about a war going on; she explains to Samsa that he has an erection. Then she leaves. Samsa watches her waddle through the city. Murakami has his Samsa wax poetic about this “warm feeling” we experienced humans have a name for, and think about how he now would rather be human than anything else, because he gets to feel this way. It’s a cute way to end, but it’s misleading. Samsa resolves to learn how to dress, and the story concludes: “The world was waiting for him to learn.” But it’s not for a sense of fashion, and it’s not for how to love. It’s love itself.