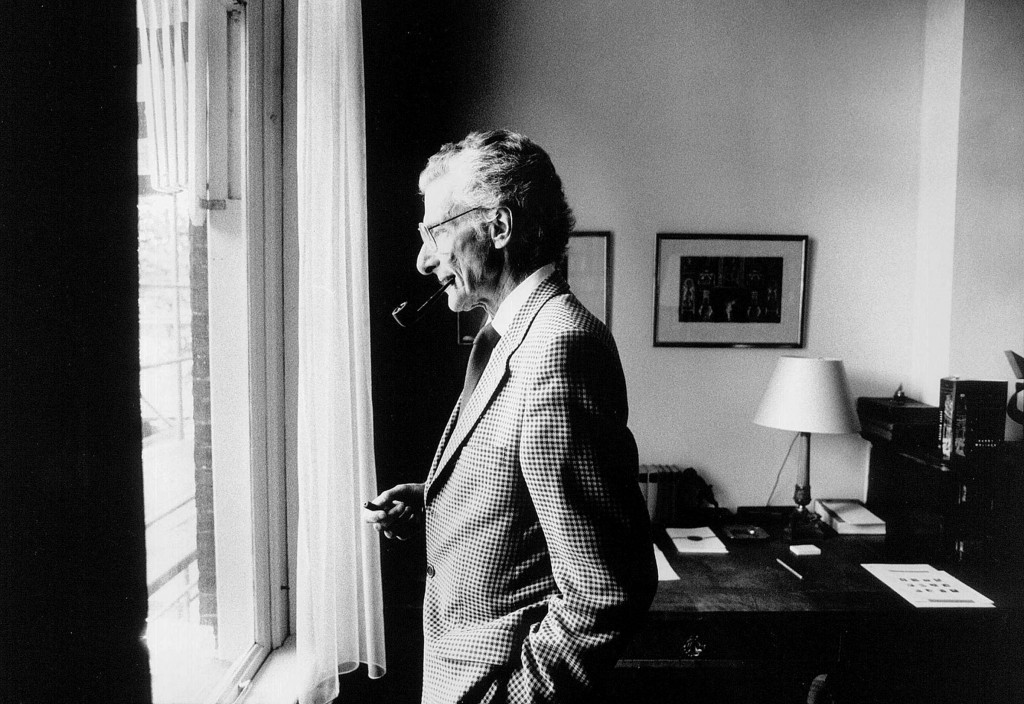

On 30th October 2010, the great Dutch author Harry Mulisch passed away—after Reve and Hermans, the last of the ‘great three’ of Dutch postwar literature to leave us. The first time I read Mulisch—it was his great novel The Discovery of Heaven—must have been in late 2010; I remember reading the biographical note in the front of the book, in which he was alive and well, only to have this new-found friend suddenly snatched away from me by the remorseless up-to-dateness of Wikipedia. Wishful memory records that I had in fact started reading The Discovery of Heaven the very day Mulisch died.

Mulisch was a prolific author with what the New York Times called a “gift for writing with clarity about moral and philosophical themes.” Considering that moral and philosophical seriousness, Mulisch really did write an unbelievable number of books. What’s more, unlike his even-more-prolific contemporary Anthony Burgess, whose entire literary output has drowned in the Kubrickian adaptation of a minor novel (a shame; Earthly Powers is as good as anything written in Britain since), Mulisch’s work has survived not one but two major film adaptations. In the books which spawned those adaptations, he has left behind two masterpieces: The Assault and The Discovery of Heaven.

The Discovery of Heaven covers the moral and philosophical themes highlighted by the New York Times—What do we live for? What happens when something unimaginable happens to us out of the blue? How much are we in control of our destinies?—but it’s Mulisch’s humour and humanity that stand out. The ending, in which (venturing a single-faceted reading) it turns out the entire novel has been building towards God’s rejection of Man, is a delicious, comic, ironic (but perhaps also deadly serious) coup de grace.

Above all, though, The Discovery of Heaven is a relationship novel: the interplay between Max and Onno is the greatest expression of friendship in literature I’ve ever read. About halfway through the book, the two men go to Cuba, where Max and Onno are mistaken for Dutch communist delegates and end up attending a revolutionary conference as a kind of joke. This is the novel’s emotional high point, where the surrounding orchestra dies away and Max and Onno’s duet soars above all else.

From there on, everything comes slowly tumbling down. Max sleeps with Ada, Ada bears a child (whether Onno’s or Max’s, it’s not clear), Ada goes into a coma, Onno flees from the world, Max traps himself in a relationship that is difficult to qualify as either happy or unhappy. Slowly, the various protagonists atomize—or perhaps, like Slothrop in Gravity’s Rainbow, are just scattered by inescapable entropy, the slow heat-death of their own private universes. Behind everything, though, there remains the background radiation, the eternal afterglow of Max and Onno’s friendship.

***

For comprehensive English-language coverage of Mulisch’s work, check out the excellent overviews at Complete Review and the Dutch Foundation for Literature.

You can find his New York Times obituary here, and a long Guardian interview here.