If there’s any sure sign of dedication to a cause, then it’s a group of UK-based translators voluntarily heading towards a day-long symposium indoors on an unseasonably warm late-September day in London. As I exited the labyrinth that is Kings Cross station to be blinded by the unexpected sunshine and made my way to the British Library, I noticed the clock on the tower of the St Pancras station. I was running late. The lack of tell-tale signs of a nearby conference about to start—no small clusters of strangers wearing identical badges, cradling coffees or cigarettes while studiously ignoring each other—confirmed it: I was late for the opening session.

International Translation Day (ITD) is an annual event, now in its fourth year. The event is hosted by several notable literary organisations in the UK: Free Word, English PEN and the aforementioned British Library, in association with the British Centre for Literary Translation, Literature Across Frontiers, the Translators’ Association, Wales Literature Exchange and Words Without Borders. International Translation Day is also supported by Bloomberg and the European Commission.

The day kicked off with a panel discussion on the future of translation, featuring a presentation of findings from new research undertaken by Literature Across Frontiers, a Wales-based European Platform for Literary Exchange, Translation and Policy Debate, into the state of international literary exchange and translation in the UK. Some encouraging statistics were—the number of translations, for example, has almost doubled between 1990 and 2010—although it’s clear the UK is still lagging behind other European countries in terms of translations published. This set off a lively discussion led by journalist, broadcaster, and translation champion Rosie Goldsmith, about what can be done to redress this situation. Between them, panelists Simon Mellor (Executive Director, Arts at Arts Council England), Kirsty Dunsheath (Publishing Director at Orion Books) Alexandra Büchler (Director at Literature Across Frontiers), and Jamie Lee Searle (translator and co-founder of the Emerging Translators’ Network) offered their own ideas on what actions could and should be taken by translators themselves to redress the balance. Having traveled for two hours that morning to reach London from the beautiful Suffolk countryside where I live, my ears perked up when I heard a call for better regional representation of translation-related activities in the UK. It is true that currently most events are centred around the capital, while translation and creative work is actually taking place throughout the British Isles. (Indeed, the British Centre for Literary Translation itself is based not in London, but in the far-flung province of East Anglia.)

A full-house at the British Library for ITD 2013

Following the opening presentation and panel discussion we split up into the first of two break-out sessions. I attended a seminar aimed at literary translators looking for their first break in the field, led by co-founders of the Emerging Translators Network, Rosalind Harvey and Jamie Lee Searle. In addition to a long list of resources for budding literary translators—from the British Centre for Literary Translation’s summer school at the University of East Anglia, to translation mentorship opportunities—Rosalind and Jamie recounted their own personal journeys into translation and gave invaluable advice for early-career translators. They also highlighted ways for emerging translators to be more proactive and show publishers their potential, rather than merely pitching a translation proposal and hoping a publisher will take a chance on them. The journey may not be an easy one, they seemed to say, but at least they could make sure we start off in the right direction.

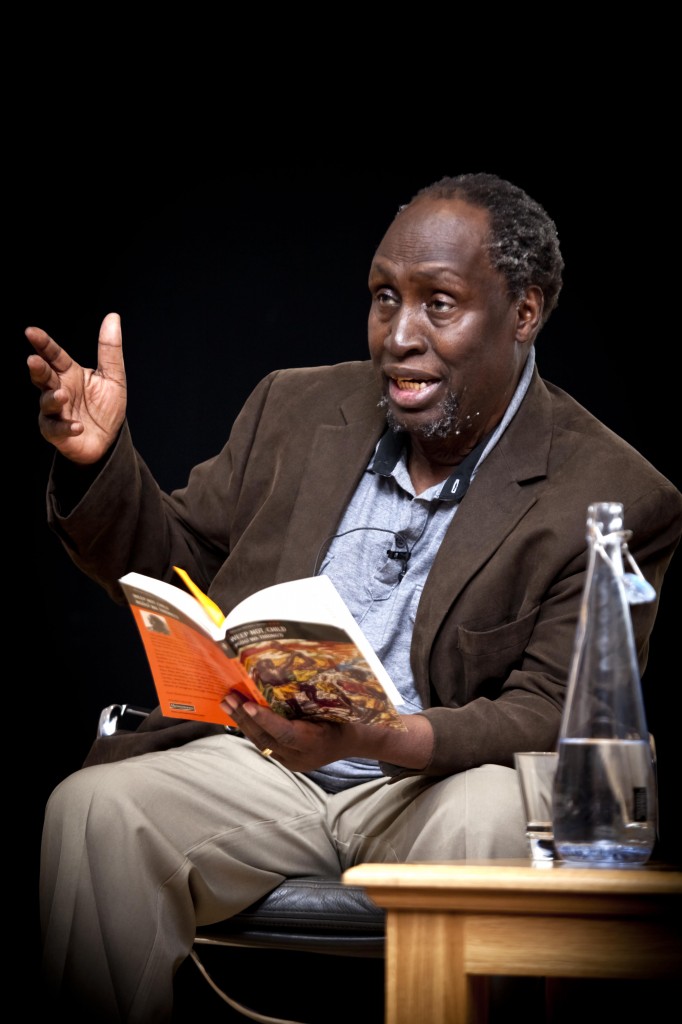

If our morale needed a boost following that discussion, then that’s exactly what we got when the special guest speaker, one of the world’s most-acclaimed writers, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, stood up following our welcoming applause, to give a bow that was somehow simultaneously theatrical and humble to the assembled translators in thanks for their work. And following on from that high note (who needs the sunshine when you have such warmth in a conference room!) Ngũgĩ’s dramatic reading, one of the most entertaining I’ve ever attended, further raised our spirits. He read a scene – standing up and reenacting each of the characters in turn – from one of his earlier novels, before delving into conversation with literary translator and Professor of Literary Translation at City University, London, Amanda Hopkinson. Together they discussed the role translation played in his life, how his writing in English was more readily-received than that in his mother tongue, Gikuyu, as well as the political challenges of being a writer in Kenya during the 1960s, a decade of tumultuous change in Africa. Following the controversial publication of a novel and a play that he co-wrote with Ngugi wa Mirii, in December 1977 Ngũgĩ was arrested and held in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison without charge. We listened as he recounted how he was still able to write from within prison, thanks to the amazing card-like rigidity of the prison toilet paper on which he wrote his next novel, Caitani Mutharabaini (1981) translated into English as Devil on the Cross (1982). It was in prison that he decided to adopt his mother tongue Gikuyu in his writing, and to abandon English as his primary language of creative writing.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o speaking at the lunchtime event

Inspired by the talk, we headed out into the main foyer for lunch and an opportunity to network with the dozens of other translators, publishers, booksellers, librarians, students and bloggers in attendance, before it was time for the final seminar for the day. Again, I attended a more practical discussion on making a career of literary translation. This time we had the opportunity to hear the experiences of three professional translators, each with a very different journey into translation as a career. Georgina Collins, Lecturer in Translation Studies at the University of Glasgow, entered translation through a more academic route. Ollie Brock, a reviewer, editor, and former Translator in Residence at the Free Word Centre, recounted the myriad jobs he took before finally deciding not to work in literary translation full time. Ros Schwartz is an award-winning literary translator and a prominent figure in the Translators’ Association of the Society of Authors. More than anything, this seminar showed that becoming a literary translator really requires passion, as it is difficult to make a financially-rewarding career out of it (at least not initially). The three speakers gave ideas on how to make ends meet while pursuing this passion, mainly through undertaking commercial translation work—translating manuals for lawnmowers may not be glamorous, but it does make for a more reliable income stream than translating modernist poetry just for the love of it.

Ros Schwartz speaking at a seminar at ITD 2013

In addition to the sessions I attended, there were several others taking place at the same time, making me wish I could have somehow cloned myself to attend all. In the morning, the Guardian’s Claire Armistead had spoken with BCLT head honcho (and prize-winning literary translator) Daniel Hahn about reviewing translations in the press; elsewhere Nicky Harman and Canan Marasligil debated the merits or otherwise of translators’ Forewords, while Christos Chrissopoulos, Sònia Garcia, and Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones spoke on the politics of translation from minority languages.

In the afternoon, while I heard about the trials and travails of “making it” in the world of literary translation, a fascinating debate around the question “When is a translation not a translation?” was going on. I’m told Timothy Adès gave wonderful readings of some translations of his, before arguing they weren’t really translations at all. Attendees of that particular seminar also heard how EU law, while existing in several languages, can’t legally be considered a translation—the different versions in each of the EU’s official languages must be considered “originals”. (Indeed, the real “original” language is a closely guarded secret.) Elsewhere, panellists and seminar attendess discussed digital projects, readers initiatives, and editing translations.

Before we all headed our separate ways, there was time for a brilliant last act: a performance segment called “Making Translations Sing” which featured songs created by acclaimed composer and singer Helen Chadwick, and performed by the composer herself and three other singers. Some of the pieces were based on interviews Helen conducted with her neighbours in London’s Dalston district, others on interview with war correspondents. In between the intense performances by her and her singing group, Helen talked about how she had translated the interviews into song theatre.

Then, just as I’d rushed in, I had to rush out, leaving the British library behind, my mind abuzz with the sense of responsibility at being able to communicate in more than one language, feeling a reinforced passion to pursue—no matter how difficult—a career in literary translation, shielding my eyes from the straggling late afternoon sun, and hurrying back down into the underground.