He often joked that he wasn’t sure about his date of birth, but most sources agree that he was born in 1923 in Dibai, Bulandshehr, India. He migrated to the new country of Pakistan in 1947, and settled in the city of Lahore. Though he often returned in his writings to his Indian childhood, his work was also firmly grounded in the cafés and lanes of his adopted city. In his novels and stories, he moved seamlessly between past and present, Pakistan and India, myth, history, and dream.

Like his close contemporary and fellow emigrée Qurratulain Hyder, Husain was fascinated by his culture’s interweave of Hindu and Muslim influences. Hyder left Pakistan after a decade’s stay; Husain, however, stayed on to witness the political and historical changes and upheavals of his new country. He commented on the war for Bangladesh, but refused to identify with party politics. In many ways, his stories embody the opposite trend to Manto’s: while the older writer dealt with reality head on, often resorting to sensational and violent events to depict the tumult of his time, Husain’s fictions often observe history through a lens of myth, blending metaphor and realism in a way that, in the very different cultural climate of Latin America, made Gabriel García Márquez an international star.

Like another eminent Latin American, Jorge Luis Borges, Husain’s knowledge of international textual traditions added several layers to his work. Subtly and over several decades he drew readers and writers away from the hegemony of foreign influences (he was often accused of emulating Kafka) into an examination of the subcontinental modes of oral and written storytelling, which had been despised and discounted by many of his predecessors who, indoctrinated by colonial and postcolonial policies of education, lauded and claimed only western influences.

It was only in the second decade of the twenty-first century that Husain saw increasing international recognition for his oeuvre. His novel Basti, the work for which he is best known in the west, was reissued in a fine translation by the prestigious NYRB Classics imprint in 2012. In India, too, several collections of his short fiction have appeared in translation, notably those by Rakshanda Jalil and Alok Bhalla. In 2013, Husain was a leading contender for the Man Booker International Prize. In 2014, he was made an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government. But a collection of his stories has yet to appear in the UK.

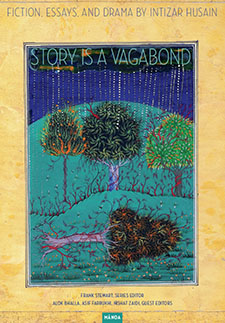

However, Story Is A Vagabond, a handsome retrospective of his work, including translations not only of his short fiction but of a play and a variety of critical and narrative essays, was published by the University of Hawaii Press shortly before his death, and it is a fitting introduction to this multifaceted and influential writer for international readers.

The selection of fictions here spans his entire career, beginning with subtle stories of contemporary realities and moving to the rich array of mythopoeic fictions for which he is best known today. Fittingly, the collection begins with “An Unwritten Epic,” a story about Partition and the events that followed the creation of Pakistan in 1947. Starting as a mock-epic chronicle of one migrant’s progress in search of new and fertile pastures in the Promised Land and his return to a world that no longer exists, it metamorphoses halfway along into the journal of the writer who is attempting to complete a novel about the life of this unfortunate migrant, Pichwa. At the conclusion of his narrative (if one can call it that), the writer has abandoned the vagaries of writing for a safe job in a flour mill—“Now I am a responsible citizen—a responsible citizen of a new nation.” Written shortly after the cataclysmic events it depicts, the story stands as one of the first and finest examples of post-modernism and metatextuality in Pakistani fiction.

After a couple of stories in the realist genre, the editors move to those reworkings of myth and parable that Husain made entirely his own. He was also enamoured of the One Thousand and One Nights; he loved, and brilliantly deployed, the story-within-a-story technique of traditional Indian and Arab narratives. Though he rarely resorted to mere pastiche, he often used the high register and ornate vocabulary of the traditions from which he borrowed.

His work often subverted the stories that fascinated him. In his occasional rewriting of fairy tales, we are left without the closure of a happy ending. In “The Death of Sheherzad,” for example, the eponymous heroine is bereft once her mission of telling stories over one thousand and one nights is completed, and laments to her husband:

That chirping, chattering Sheherzad who had entered your palace died long ago . . . you granted me life but snatched my stories from me. When my stories ended, my own story ended with them.

Subversions are also significant in his borrowings from Buddhist lore (to which he was particularly drawn). In the story “Leaves,” for example, the protagonist renounces abstinence and meditation for the never-ending agony of desire; in “Complete Knowledge,” a teacher abandons his student to set off on a journey of knowledge:

“The journey of knowledge?” Manohar [the student] asked, even more surprised. “You are a man of wisdom. What journey of knowledge do you still have to undertake?”

Sampoornandji retorted, “who has ever attained complete knowledge? Human beings must search forever.”

“The City of Sorrow” is a fine example of another genre which Husain pioneered: timeless, abstract but visceral depictions of existential despair, in a world emptied of conscience, which some might compare to the works of his contemporaries, Beckett and Ionesco. Discussing this story, editor Alok Bhalla provides a historical context in his incisive introduction:

. . . the story is about people who are no longer ashamed of what they do. Three men, without names or faces, describe who each of them had raped and killed repeatedly during the war in East Pakistan [1971]. Unable to mourn, unable to repent, they become horrors to themselves . . .

Unlike his contemporaries, Husain often refused, in symbolic stories of this sort, to historicise his settings or to pontificate on the events that inspired them. While this may have caused some of his critics to accuse him of an apolitical, universalist stance, it actually has the effect of making the stories resonate in any era in which we read them, especially in today’s war-wracked world.

In the last decade of his life, Husain became an iconic public figure. With the rise of international literary festivals in Karachi, Islamabad, and Lahore, he regaled halls packed with several generations of eager listeners with his erudition and his skills as a raconteur. He discoursed on traditional forms of storytelling, ranging from medieval Indo-Persian romance cycles to the canons of Hindu and Buddhist epic, myth, and parable. He could deliver impromptu lectures on any genre, with his iconoclastic wit and the occasionally contentious irreverence that his position as the éminence grise of Pakistani literature allowed him. These thoughts are presented in a coherent and cogent form in the essays on storytelling and craft that make up the final section of this timely and comprehensive volume. Providing a key to his use of myth, parable, and memory, they are a valuable introduction to his immersion in local and in world literature, his technique, and its evolution and development over the years.

These essays, as well as the stories selected for this volume, are translated by a number of eminent figures including the aforementioned Bhalla, as well as Pakistani writer-critic Asif Farrukhi, Indian academic and translator Rakhshanda Jalil, and American scholar of Urdu, Frances Pritchett. (Unfortunately, the original dates of these texts are not included.) Husain’s variegated prose style, with its sometimes abrupt shifts between a spare, dry twentieth century sensibility, ornate embellishments from the Persian-inspired medieval storytelling tradition, and the elliptical mode of Buddhist parable, is notoriously difficult to capture in English. It is to the credit of the translators and editors of this volume that they have managed (though some might feel that a certain uniformity occasionally flattens the effect of the originals) to maintain a level of translucence through which Husain’s distinctive intonations echo and resound.

Husain’s novels located similar trajectories to his essays and short fictions in recognisable urban and parochial milieux, shifting from scenes in cafés and homes to the narrator’s musings, imaginings, and dreams of an idealised past that had been destroyed by hubris and human folly. The Sea Lies Ahead, a chronological sequel to Basti, has also recently appeared in a translation by Rakhshanda Jalil: originally published in 1996, it’s a more expansive performance than its precursor, at twice the length, swerving from long passages of domestic gossip and expository naturalistic dialogue about the migrations and resettlings of its many characters, to scenes set in distant historical periods, for example in Arab Andalusia. At least in translation, this approach comes across as diffuse and unfocused, and one is left longing for a slender novella buried in the debris of the past: a story that directly addresses the dilemma of those migrants who were told in the 1960s by the dictator General Ayub Khan that if they weren’t content with their circumstances, they could just walk right into the sea of Karachi.

I first encountered Husain’s essays and stories in translation in the early 1980s, but it was not until I read stories such as “The City of Sorrow,” “Leaves,” and “An Unwritten Epic” in the original Urdu in 1991 that the full impact of his innovations became clear to me: how he had influenced an entire generation, and pioneered—without knowledge of, let us say, his contemporaries Márquez and Cortázar, who were making parallel experiments elsewhere—a kind of fantastic realism in his fiction which transformed the Urdu short story and, to an extent, the Pakistani novel. I learned enough from his forays into surrealism and fable to detect a change in my own relationship with tradition and realism; along with his great contemporary Hyder, he enhanced my awareness of the importance of fractured and disjunctive narratives in conveying the individual and collective truths of displacement and exile.

I met Husain many times during the last twenty years of his life, in Lahore, Berlin, Karachi, Islamabad, and London. I have a copy of Basti signed in Urdu to “my dear brother Aamer.” When I wrote and published a handful of stories in Urdu, he wrote about these (in English) in his regular column in the literary pages of DAWN. Above all, he was amused that when everyone was rushing to write in English, I, as a long-term expatriate and resolute Anglophone, should return in middle age to the mother tongue I’d never written in before. From someone who served our common language so long and so well, it was an enormous tribute.