Xianzai Shi is not one of those tiny journals that burrows into a dusty nook and leaves only a slender spine visible to the browser. Although it is prominently displayed in the poetry section, it still manages to hide in plain sight, and it occasionally takes other forms (e.g. one issue disguised itself as a fashion glossy, with the poetry written on pictures of scantily clad models). The style of the poetry within the covers varies tremendously from issue to issue, but all of it is simultaneously forward-thinking and dedicated to engaging with contemporary society. This paradoxical position, perched between radical counterculture and anonymous assimilation, is precisely what is intended by the loose collective that puts out the magazine. Like a virus, Xianzai Shi exists in a careful symbiosis with the cultural noise that surrounds it, deriving nourishment from that which it ultimately aims to remake entirely.

There is a biting insouciance and irreverence at the core of Xianzai Shi, a complete refusal to be yoked into any sort of rigid system or be hampered by pretension. The magazine is released on an irregular schedule, with a different theme and a different chief editor for each issue. The five poets at the core of Xianzai Shi—Hsia Yü, Yung Man-Han, Hung Hung, Tseng Shumei and Ling Yü—meet only when they feel so moved or when they have ideas for a new issue. And it is often difficult to assemble all the poets together, as they are a cosmpolitan and often far flung group. Both Hsia Yü and Yung Man-Han have lived for significant lengths of time in France, while Tseng Shumei currently resides in Beijing. They are even quite different stylistically: Hsia Yü's work (which has been featured in these pages) has ranged from OuLiPo style experimentation to, in recent years, an increasingly ornate use of language, while Hung Hung favors a conversational style and produces work that is intensely socially engaged.

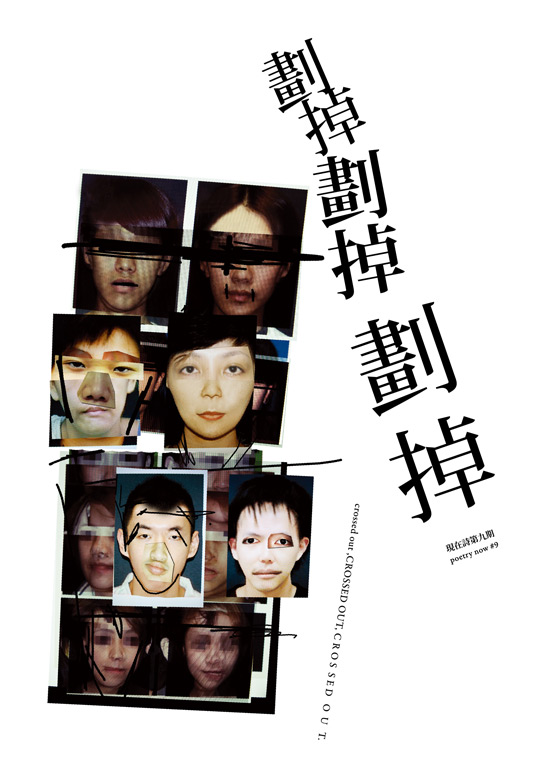

Despite their differences, the Xianzai Shi poets are united by a belief in a loose, global kinship of eccentric literati whose role is to criticize and illuminate the society in which they reside. Their latest issue, released at the beginning of Feb 2012 and entitled "Cross it Out, Cross it Out, Cross it Out!" is characterized by a bitter humor: A poem by Yung Man-Han contains an extended series of jokes about male fertility supplements, and another by Hsia Yü transforms a news article on former Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian's first day in prison into an account of a breakfast routine. This issue is made up of poems produced through the selective erasure and defacement of newspaper articles, movie reviews, art exhibition guides and even other poems—that is, it is produced through the selective obliteration of Taiwanese mass media culture.

In many ways, this vision is actually a very traditionally Chinese one: the poets who live outside the bounds of society and mock its conventions, who meet together and rejoice in free, bibulous gatherings with their compatriots. Indeed, the poets of Xianzai Shi are contrary but never quite iconoclastic. Their rebelliousness is a coy, calculated pose; it is very clear that these poets are clearly and deeply engaged with the Chinese literary tradition. In the interview below, Yung Man-Han even quotes the Jin Dynasty calligrapher Wang Lizhi. From a certain perspective, this issue of Xianzai Shi can be seen as fundamentally conservationist rather than radical. By editing out the ceaseless noise of Taipei media and capital, these poets have precipitated the simplicity and beauty of Classical Chinese out of the modern vernacular.

Both contemporary and nostalgic, iconoclastic and reverent, global and local, lying comfortably on the bookshelves between tabloid gossip and the I Ching, Xianzai Shi is perhaps most of all Taiwanese—a remarkable product of this contradictory cultural eddy in the East China Sea.

—Dylan Suher

ASYMPTOTE: How did Xianzai Shi get started?

LING YÜ: Hung Hung, Tseng Shumei and I were all colleagues together on Modern Poetry; Hung Hung and I were also successively the chief editors of that magazine. In October of 1997, after Mei Xin, the publisher, died, Modern Poetry came to a halt. At that time, the poet Huang Liang hoped to be able to put together a poetry publication and he very enthusiastically pushed for me and Hung Hung to meet. Before long, Hsia Yü came back to Taiwan from France. Later, Yung Man-Han joined up. Everyone really wanted to put a poetry magazine together.

The name Xianzai Shi (Poetry Now) was suggested by Hsia Yü. She said "now" ought to replace "modern," and the suggestion was unanimously adopted by everyone involved.

YUNG MAN-HAN: Of all the people working on Xianzai Shi, three were originally Modern Poetry staff members. That publication, established in 1953, began to publish Taiwan's "modern poetry," and all of Chinese literary history will record this fact: sixty years ago, it was Taiwan, without a doubt, that was on the forefront of Modernism within the Sinophone world.

Xianzai Shi's founding declaration was:

Xian (to appear) is action;

zai (to be) is happening;

Shi (poetry) is just poetry.

In 2001, at the beginning of the century, we proclaimed that gorgeous vision. I don't know where it came from, and who knows where it's heading. The "modern" era has already passed. "Postmodernism" will come to a stop one day. "East" and "West" have both been left in the dust. We offer this: in the future, every moment of the now will transform into poetry. Poetry is a verb; it is the poetic feeling that drives those of us human beings who truly live.

I hope that Xianzai Shi is not only a poetry publication. She is a century's call to action. She belongs to all mankind, illuminating the consciousness of the essence of this era, an era without a beginning and without an end.

HSIA YÜ: In 2001, I returned to Taiwan for a short stay, and Hung Hung called me to get me to come out and see a few friends. We all of a sudden decided to organize a poetry publication together. It seemed as if, after so many years of living in France, by being in that little coffee shop in the neighborhood of National Taiwan University, I was altogether refreshed. I didn't think too much about it and just went along with whatever the others had planned out. After half a year, I returned to France, and after half a year in France, I came back to Taipei to stay. I remember that in those first three years, everyone was always having great fun at the editorial meetings. We never stopped coming up with ideas. We drank. We laughed our heads off. A few times, because we were too boisterous, the café owner broke up our meetings.

ASYMPTOTE: Xianzai Shi is organized in an uncommon way for a poetry magazine, especially by the standards of Western readers: it's run collectively and every issue has a different editor-in-chief. What kind of advantages does this have over more traditional ways of running a magazine?

LING YÜ: For each issue, we usually consult with everyone as to what the theme might be. Whoever has a good idea just puts it out there, and then we discuss it together and decide. The most fun is the discussion part; we'll often push the discussion way, way out there, and then, only through the efforts of some sober-minded soul, do we manage to pull it back down to earth. The five of us are not alike in a lot of respects; maybe our differences add to the richness of the discussion. From the beginning, we at Xianzai Shi never wanted to follow rules. Typically, poetry magazines are rigorously organized, or they have a vast number of members, or they give deference to seniority. But we're the only five members of Xianzai Shi, and we don't like the traditional model. On the contrary, we want to put out a fun and interesting poetry magazine, not create a complicated bureaucracy.

This kind of model has advantages, like "a sheet of loose sand." It's only when we publish the magazine that we see the sand come together into something concrete.

YUNG MAN-HAN: Everyone knows what children's games are like–you make a ruckus, just for the fun of it. This is not unlike the editorial process we've stumbled upon. Of course, we also get into real arguments—because we always speak what's on our minds. But it always blows over eventually. Ordinary organizations have a structure, a set space; we're more fluid. We are all there is to the editorial team, so when people get emotional, we stop, have a good drink, start to joke around again, and then the ideas happen. Didn't the Jin Dynasty's Wang Xizhi say, while waiting for his literati friends, "A wine cup flows down the stream; others will abandon themselves to reckless pursuits; but he himself will feel content"?

HSIA YÜ: We very seldom convene a meeting, and when we do meet, when it comes time to go our separate ways, we always mistakenly think that all that laughing and bustling about was putting the magazine together. Nobody takes notes, there aren't even pictures taken, we don't remember what we've said after a glass of wine...later we'll start to argue, because we certainly have no money, and the real editing work is quite complex. Assembling the issues, I'm always filled with regrets. I ask why I've made it so hard for myself. Once it's published, I'm always unable to move it off the shelves. Everyone is very busy, and although I'm not busy, I have no ability to concentrate. Our way of doing things—directionlessly, goallessly, which we jumped on thoughtlessly—is it really the best way? I don't know... Man-Han said it beautifully, but I'm also saying it like it is: Really, I swear, almost every issue I'll say that this issue will be the last one, but every meeting is always too much fun and I'll forget what it was that I said.

ASYMPTOTE: How did you come up with this issue's theme, "Cross It Out"?

HUNG HUNG: "Cross It Out" was Hsia Yü's suggestion. She wanted to do it as an exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum. Because it seemed like fun, the rest of us were happy to go along with it, but everyone had a very different way of playing with the concept. Those visitors to the exhibition who participated and left behind writing or marks clearly also had very different thoughts on the matter.

HSIA YÜ: It was initially a plan for a book of my own, but I gave the idea to Xianzai Shi. First we were invited to exhibit, and then we collected the results of the exhibition into a magazine.

If I concentrated while reading the newspaper or reading magazines or reading books, I could always see a subtext that had nothing to do with the topic at hand. The poetry collection I had imagined was simply the unveiling of this subtext. You see there's a fundamental contradiction: You first need to focus before you can continue to read, and then you stray from the topic. You are taken by the simplest phrase to another place.

This certainly isn't all my idea; it's a Dadaist idea originally. But this era isn't the same; text and context are different now than they were then, and there's a vast difference between the feeling they had and the feeling you get now from crossing out to produce a new piece of writing.

YUNG MAN-HAN: Note that the end result of crossing-out has to be poetry. Even if it may never attain the standard of an original creation, it must at least be a piece of writing that's both fun and worth reading. A more practical way of thinking about it is: In this age of information overload, one's brain can get swollen from too much information; from time to time one needs a crossing-out in order to put it back into shape.

Writing can disseminate too much information. You look and you look at a piece of text and you just want to edit parts of it out. Ancient classical writing was weighty and very difficult to cross out, but today's vernacular writing has room for a substantial transformation. In short, crossing out as a practice has much to offer, it may even herald the advent of a new era of classic prose.

LING YÜ: Every time I read a book, or a newspaper, I inevitably feel the impulse to cross out. Modern people are too verbose; they often don't know how to stop talking. Because of this, sometimes I also can't help but want to play this crossing-out game.

ASYMPTOTE: Could you explain what the process of putting together this issue was? How did you choose the source materials?

HSIA YÜ: All of the materials have a connection with the period of the exhibition—from the start of the exhibition in November of 2008 to when it ended. We started to edit the magazine about a year later. The materials are a year's worth of scattered newspapers, magazines, film festival guides, etc. None of these materials were selected in advance. Our student assistants went to a recycling center and bought print materials by the pound for the exhibition. Most of the materials are from tabloids like Next Magazine—from a heap of gossip mags. This is really all poetry salvaged from the junk heap.

LING YÜ: I took a completely random approach to my selection, which is why I enjoyed it all the more. If you consciously picked the material with poetic potential, it wouldn't be half as interesting; you'd have no way of revealing the spirit of the text.

ASYMPTOTE: In this issue of Xianzai Shi, not only has text been effaced, but images as well. Could you discuss the connection between these images and words once they've been through this process? In your opinion, in this era of image overload, do you believe that the relationship between the language of poetry and images is a kind of resistance or a kind of cooperation?

LING YÜ: Both. Sometimes it's resistance, sometimes it's summoning forth, sometimes it's cooperation.

HSIA YÜ: Both. Sometimes there's no resistance, sometimes there's no summoning forth, sometimes there's no cooperation.

YUNG MAN-HAN: Personally, I think the words "overload" and "resistance" are a little too strong; people who keep their eyes wide open are always pleased. In our exhibition in 2008, words and images breathed together as if they were one. In that little exhibition space, there were Italian-style transparent table and chair sets for visitors to do their crossing out. There was a couch Hsia Yü brought from home that had been torn apart by her dog, with a bunch of loose threads and springs popping out. There were newspapers and magazines all over the floor. We stayed in that tattered place and couldn't bring ourselves to leave. Now that space has become print. "Resistance" or "cooperation" seem like irrelevant words to me; we simply know what's visually appealing.

ASYMPTOTE: In this issue, apart from Chinese poetry, there are several poems in French and English, some contributed by Taiwanese poets and some by non-Taiwanese poets. Additionally, for some of these poems, you preserved the original, untranslated texts side by side. Would you say there are any connections between crossing out and translation?

LING YÜ: When we had the exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum, a few friends from abroad came to participate, so we invited them to join in the festivities. That's how a few foreign language texts came to be included.

Between crossing out a language and translating a language, there is a subtle connection;

Translation is sometimes just crossing out.

YUNG MAN-HAN: We said "Poetry is just poetry," there's no way to translate it. These English and French texts that are revealed after being crossed out all have a great poetic quality. How can you translate them? From crossing out the content of these publications to what's retained, the whole appearance of the thing is like giving birth. It's strange. How can one think of "translating" certain phrases?

HSIA YÜ: After crossing out an alphabetic language, you leave behind the sound; after you cross out logographic languages, you leave behind images. How would you want to translate sound? How would you want to translate images?

ASYMPTOTE: Particularly in the longer pieces, any piece of text that isn't crossed out is potentially part of the poem. Therefore, until the writer delineates the poem, the poem is theoretically endless. How does this concept relate to how you ordinarily think about writing a poem?

LING YÜ: When composing your own work, you're often confined to the words you're used to using. Crossing out, on the other hand, if only by dint of having to work with other texts, causes you to go beyond the scope of your own familiar vocabulary. However, the paradox is every person still picks out the words to which they are accustomed, so what's produced is still in the style you already have. So what, finally, is your relationship to the text? I'm also curious.

HSIA YÜ: I think the main ideas here are to nullify the connection between words and to fragment continuous meaning. Poetry is initially the fracture of connections and significances, but after all you want to have a kind of "poetic adhesion." I feel that the difficulty—as well as the relative attraction—of the method lies in making a text that runs counter to the original text but at the same time looks natural where it's difficult to say if these "poems that suddenly appear" (poems that are left over? Superfluous poems? Poems that seem filtered out?) existed in the original text or not, right? Of course, there are exceptions; for example, there are certain sculptures where as soon as you look at the original piece of wood, you know in your heart what the sculpture will be, and then you freely go along with that form with your knife.

All in all, I still would like to attribute it to a kind of encounter: Words without any link have no significance, but they still form an encounter.

ASYMPTOTE: Crossing out reveals the creative process; it reveals words in the process of being deleted, selected, and rearranged. For example, Hsia Yü's poem "Rub Ineffable" is a dismantling and reconstruction of her earlier work, "Ventriloquism." Do you feel that a "work" is eternally a kind of "process," a perpetual state of becoming?

LING YÜ: All writing can be reworked. "Works" are eternally a kind of "process," a state of becoming. As far as the authors are concerned, maybe it's already finished; as far as the readers are concerned, it's eternally unfinished.

HSIA YÜ: As far as readers are concerned, writings are, of course, in a kind of fluid state, a multitude of meanings come from this appearance of fluidity and readers pick the ones they need. But for the writer, sometimes after finishing a poem you indeed hear a ta da sound, like the sound of something locking or unlocking; the sound of a kind of completion. It is not that we can't rewrite the work, but that there is no need.

ASYMPTOTE: I felt that the issue's most powerful aspect was how it transformed the language of news reports into the language of poetry by the creative technique of crossing out. Through the ability of poetry to distill meaning, news is no longer news, but something that, as Hsia Yü puts it, "opens up an undiscovered territory in the midst of reality." Hsia Yü's poem, "I Haven't Eaten All Day," uses an article from the Apple Daily on A-Bian's first day in jail. However, we cannot see anything of the original topic in the poem; the newspaper article has already been "distilled." Is this process of turning something into poetry a kind of depoliticization? What do you think poetry's position ought to be?

HSIA YÜ: Before I responded to your question, I noticed that you used the nickname "A-Bian" to refer to Chen Shui-Bian—don't you think that already "depoliticizes" this piece? Or could it be that you don't think that giving a politician a nickname is extremely political?

I feel that, in these times, we've been degraded and polluted by the language of mass media. It's something to which we are almost completely already accustomed. Many reporters record a mixture of their own self-obsessed feelings and preferences. They try their hardest to use their own vocabulary and style of language and deploy the tone of short stories, essays or magazine articles to the point that it's almost in the style of a movie script, telling us "the truth of the matter." I, on the other hand, strive for the neutral tone that news reporters should have, but the contrast makes it actually look, unbelievably, a little like poetry. If this style is the "depoliticization" of which you speak, clearly all of us in the modern world have been very seriously contaminated. We've become so used to news language that is politicized or sensationalized or possesses that certain volatility one finds in disaster scene reporting that neutral language has become poetry, although I'm actually not opposed to neutral language.

LING YÜ: The politics of poetry fundamentally does not lie in whether it has a connection with political news or politicians. Some people's political poetry merely repeats the news; you couldn't tell from their poetry what they themselves think.

Poetry's duty is to avoid superficial and shallow politics—which you can get by simply watching the news. Poetry, including political poetry, must first be true to its poetic roots.

ASYMPTOTE: In some of these poems, particularly Hsia Yü's "Fearing to Return to that Rather Obsolete Language," the way the cross-out was done reminded me of how the feminist theorist Hélène Cixous describes women's writing:

You've written a little, but in secret. And it wasn't good, because it was in secret, and because you punished yourself for writing, because you didn't go all the way, or because you wrote, irresistibly, as when we would masturbate in secret, not to go further, but to attenuate the tension a bit, just enough to take the edge off. And then as soon as we come, we go and make ourselves feel guilty—so as to be forgiven; or to forget, to bury it until the next time.

(Trans. Keith and Paula Cohen)

Additionally, issues of the body reoccur continually in these poems: the "plastic surgery" on the front cover, scarring, illness.... How is cross-out linked to the body, to gender, to marginalized voices?

HSIA YÜ: One might actually wish to treat crossing out as a dash. But if you insist on speaking of an analogy between crossing out and sexuality, I, on the contrary, feel that with crossing out, the cross-out more resembles an engorged penis: you have thin and thick, additionally, you have long and short, [laughs], also, you have spiral ones.

I feel like responding to these questions is like entering a kind of concert where the conductor provides commentary—it's like: "carefully listen to the sound of this flute section, for it represents the sound of slipping on this frozen lake"...that sort of thing.

LING YÜ: Crossing out, to a certain extent, is closer to creation. It's just like plastic surgery. There's an ideal template in your mind and to replicate this ideal template, you'll need to use a knife. When a plastic surgeon uses a knife, on one hand, he's scared; on the other hand, he's also full of anticipation. Exercising total power over this domain, he is free to do as he wants and free to be who he wants. He rebuilds another universe.

ASYMPTOTE: In "Fearing to Return to that Rather Obsolete Language," you went even further and deleted the poem that you had created through crossing out, leaving only the title untouched. Additionally, you deleted Gwyneth Paltrow's picture in the original source material. What is the significance of this deletion of a deletion?

HSIA YÜ: The content of this poem and the second deletion of that content was merely the best exemplification I could think of for the topic— "Fearing to Return to that Rather Obsolete Language." In my poetry, this sort of adherence to the topic is pretty rare; I've been criticized quite often for going off-topic.

I didn't intend to delete Gwyneth Paltrow's image, but I also couldn't think of any reason to keep it, and anyhow I didn't like the film it came from, and I also don't like confessional poetry.

ASYMPTOTE: The source material for Hung Hung's "Opened" seems like it came from an advertisement for a housing development. Is crossing out a way of reclaiming contaminated commercial language?

HUNG HUNG: Actually, it was an ad for new students originally entitled "School's Started." When I started to play around with crossing it out, I just saw a forest of words. It was a kind of subconscious crawl; I just ate whatever I came across that suited my appetite. Perhaps readers would know better what it was that I wanted to say, but I certainly don't.

ASYMPTOTE: I noticed that Hsia Yü's piece "His Works and Him" uses a simplified Chinese translation of Jacques Derrida's The Animal That Therefore I Am as source material. How did you come across this text? Why did you use images and the completely crossed-out original text itself as content, and not put together a poem? Did you take these pictures yourself? Through these images, is there a dialogue (or a resistance) with Derrida's The Animal That Therefore I Am? Is there any influence of post-structuralist thought on your creative work?

HSIA YÜ:

1. I bought this book in Taipei's simplified character bookstore, the way you'd buy any book.

2. Because this person herself had mistakenly thought that, in this world where mankind is the lone sentient being, animals have no words to explain themselves, I respected the speechlessness of animals and, consequently, I remained speechless.

3. Yes, I took these pictures. I recorded a mischievous dog in my home in the process of gradually dismembering a sofa, but my watching over him (without intervening) was completely indulgent, even loving. That these images were paired with Derrida was an accident, or maybe it wasn't, because I was reading him at the very same time.

4. I really like this book, The Animal That Therefore I Am, and I thought about it for a long time. Of all the books that I've read, I've never before read anyone who's written in this way about this topic.

5. Does post-structuralism influence me? I hope there isn't an influence. My life is already confused enough as is.

YUNG MAN-HAN: This was the work that interested me the most out of the whole exhibition.

We "cross out" text, but Hsia Yü lets her dog "cross out" a sofa. Unfortunately, the reproductions in the magazine couldn't be clearer; only the luster of the original pictures reveals the expression of the dog as his fascination with the sofa grew–it looked vividly like a person's face. But he's an animal, not a person. The space he was in was too small; he destroyed everything around him; he chewed up heaven and earth. Honestly speaking, Hsia Yü used this sofa in her house to let the animal grind its teeth on it every day so that he would develop an animal nature. This piece truly moved me; there is a thick and fierce poetic significance beyond the text.

ASYMPTOTE: Inside this issue, twenty pages of a math textbook are made into a poem. We particularly would like to hear what your thinking was. Why choose math as a source material? We noticed that you retained the mode by which the poem was transmitted (that is, you included a photo of the package): do crossing out and "transmission" have something in common?

YAN JUN: I was browsing a bookstore in Changsha. The bookstore was very old with a great atmosphere, but there weren't any books worth buying. This book jumped out at me, only because the name of the book was interesting. I figured I could use it to tell fortunes. As for math, I think it must have a poetry to it; unfortunately, I can't tell, and I have no way to discuss it, because I know absolutely nothing about math. We always turn those objects we know nothing about into poetry, a kind of self-deception. But I make the things I myself know nothing about into a total mess —profanity be damned; and it feels great. In the final analysis, what I put together wasn't really the language of math at all; it was instead the language I saw.

HSIA YÜ: You paid attention to the fact that we retained the way the poem was transmitted—a package? Yes! We retained the poem's transmission—a package is precisely for making you pay attention to the fact that we retained the poem's transmission—a package, then why would you pay particular attention to the fact that we retained the poem's transmission—a package? That is because we took care to retain how we transmitted the poem—a package!

ASYMPTOTE: There are seventeen poems in this issue that were anonymously authored—why so many anonymous pieces? What are the origins of these works? What is the relationship between crossing out and anonymity, or crossing out and authorship?

LING YÜ: When we had the exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum, we designed a game that we could do together with the visitors. We collected all kinds of magazine and newspaper articles together, prepared a few pens, and allowed them to play around with crossing out at the exhibition. For this purpose, we also went out and bought a transparent box, and let people deposit their writing into this box once they were finished. Later, when we examined the results, we discovered that some people didn't put any kind of name; this is why there are so many anonymous pieces.

Since you asked, I've also started to consider the reasons why they didn't provide their names.

Maybe they weren't aware of the power of text and just thought of this activity as a mere game. Or, they hadn't really understood cross-out, or realized the value or significance it had for them personally.

Here, one should make use of the phrase, "the silent majority."

The writing of a text should have many kinds of "anonymous masses." You can't help but feel frustrated: Until now, all the extant writing of mankind has been nothing but the tip of the iceberg.

ASYMPTOTE: For Hsia Yü, this is not the first time you have experimented with these kinds of formal restrictions. The poems in your book Pink Noise were written "in collaboration" with a piece of translation software. How does the work in this issue of Xianzai Shi relate to your previous work?

HSIA YÜ: I am fascinated by formal constraints, which I utilized in my poetry collection, Rub Ineffable. I am also fascinated by the opposite—objects that expand without limit. For example, Xianzai Shi's second issue, which I edited, was called "Publication Guaranteed." That issue's only guideline was: so long as you submit something, I will publish it. Can you imagine what a big risk it is for a poetry magazine to put out a notice like that? You have absolutely no way of predicting how much a reader would submit—what if somebody submitted two hundred poems? And all of those 200 poems were crap? What's more, I gave my word beforehand that I'd accept absolutely everything. I finally put together a treacly, pink phonebook-sized poetry magazine; you can only say that I was too lucky.

Pink Noise was both limiting and broadening. In any case, I like both.

ASYMPTOTE: In a recent Believer essay, the writer Jeannie Vanasco examined the technique of erasure:

Why erase the works of other writers? The philosophical answer is that poets, as Wordsworth defines them, are 'affected more than other men by absent things as if they were present.' The more practical answer: compared to writing, erasing feels easy. But I am here to convince you: to erase is to write, style is the consequence of a writer's omissions, and the writer is always plural. To erase is to leave something behind.

How does this view of the technique compare with your own views? Why erase the works of other writers? Are poets 'affected more than other men by absent things as if they were present'? What do you leave behind when you erase?

HSIA YÜ: In the Contemporary Art Museum show, we blew up every piece of writing, framed them, and hung them all over the four walls of the gallery. After the two-month exhibition ended, every piece of writing hanging on the walls was totally unrecognizable. The visitors had further defaced them. Most of the defacements were the kind of graffiti that simply showed that they had been there: happy birthday to X written on one, I love you X written on another, some had painted beards and glasses, and there were also certain pieces of writing that had "fart" or "crap" written on them... Of course, there were also further defaced phrases as well as highlighted phrases. Every few days or so, we'd go and look and discover that the writing was not the same. When it came time to edit the magazine together, I was really troubled: should I use the "crossed out" or the "crossed out again" or the "crossed out yet again" version? Finally, owing to "commercial considerations", we decided to reprint the clean versions (Because so long as you add one cross-out to a work that's already been crossed out, in theory, that piece becomes yours—in the end, there would be no way for anyone to sign their names) (and also, who would want to buy it)—is this piece of business really worth mentioning? All of our works in the exhibition had been erased completely, without exception. That anonymous collective of defacers—were they to collectively interrogate us—might ask: why are you allowed to, but not us?

LING YÜ: Erasure, cross-out is a kind of hegemony, a kind of exercise in authority. When text becomes a kind of power, relatively speaking, there also is a kind of power of erasure in our hungry stare. When we conduct an erasure, a cross-out, it's creating a paradise of your own language, one which replaces the power of the original author of the text.

ASYMPTOTE: Do you feel that, to a certain extent, Taiwanese history counts as a kind of cross-out or a kind of erasure? Looking at your lives and your careers, do you think that crossing out or deletion is connected with your development as artists?

LING YÜ: In terms of responding to your question, crossing out or erasure is an immense historical problem. History, since ancient times, is simply a constantly repeating cross-out/erasure. Taiwan's history is no exception.

In the text of an individual life, we often cross out or erase certain things, and what's left becomes another text of ourselves.

In the history of the development of modern Taiwanese poetry, there are also some people who cross out or erase with a broad brush. But this kind of cross-out or erasure is sometimes done too early, too roughly. We should be conscious at all times and be readjusting at all times, in order not to abuse the hegemony of the current era.

YUNG MAN-HAN: If one were to say "yes," this question would be suspicious, for it seems to lure the respondents into a political controversy. Actually, any nationality or individual has a tendency towards crossing-out/erasing their own history—for example, Singapore, America or Ireland, who knows how much they've crossed out to become the way that they are today. In Remembrance of Things Past, Proust wrote that literature is the only means of recovering lost time. This is also Xianzai Shi's belief: To make the objects that are flowing or passing into time into poetry.

ASYMPTOTE: What poets or styles of poetry in Taiwan are you excited about right now?

LING YÜ: These past ten or so years, contemporary Taiwanese poetry has entered a period of flat, gentle decline. However, Hsia Yü's various types of experiments with contemporary language have caused another pinnacle period to arise. The breakthroughs in language that she has demonstrated have been—as far as I, a poet who majored in Chinese, am concerned—a great inspiration.

The colloquial poetry which Hung Hung advocates also loosens up my language.

Additionally, Ye Mimi and A Mang's great efforts in poetic language have given me a lot of inspiration.

Especially in Taiwan—which is known as the place that retains the most Chinese culture and tradition—the demands on modern poetry are still traditional. Tradition sometimes makes people feel safe; sometimes, it makes people feel decrepit; sometimes, it makes people feel smothered.

Fortunately, these poets don't look back and are always looking forward; they are breaking with tradition, and are unsentimental in doing so. This kind of spirit is very contemporary/modern, very valuable.

ASYMPTOTE: Can you tell us your plans for the next issue?

HSIA YÜ: Regarding the still not completely certain future, I need to first mention a few important things, for example:

1. We accept contributors from other cities to join in, for example, Beijing's Yan Jun fashioned a tiny chop for Xianzai Shi's seventh issue.

2. We accept other people to be guest editors, like Yang Xiaobing, who edited Issue 10, "Relentless Poetry."

3. We accept strongly original art editors who will lead our magazine forward with a fierce aesthetic.

4. Starting with issue eight, we began to accept the sponsorship of Taipei's Psygarden.

5. We are also not opposed to other sponsorship.

LING YÜ: As for plans for the next issue, we are still waiting for Tseng Shumei to return from her job in Beijing. Everyone will happily reunite, and then make plans again. Of course, we'll first find an interesting little bar, eat some good food, drink a little wine and then talk it over.