by Ma Yimu (trans. Poppy Toland)

Photo provided by Xin Jing Dian Wen Hua

There are two Han Hans.

One appears on magazine covers and in newspaper headlines—the Han Han at the centre of a vortex. His words and actions are broken down, frame by frame, into slow-motion, so they can be discussed and consumed, again and again. The other secludes himself in the suburbs, preferring a life of minimal social interaction, all the better to maintain a distance from the world.

This is the second Han Han—the Han Han who writes the novels.

The first time I met Han, one of the top race car drivers in China, he drove me to the Shanghainese housing complex where he lives. Recognising the car some way off, the security guard gave a salute and opened the gate. A metre away, Han suddenly decided to spin the car at a ninety-degree angle and enter sideways. Turning sideways to take on the world—you could almost say that this is the attitude of Han's fiction.

"I was born with no name, parents unknown. Yet, without knowing how or why, I have a master." This is how the narrator opens Riot in Chang'an City. Endowed with the martial skills necessary to unite jianghu—the imaginary milieu of martial arts novels—Han's protagonist has a special calling, whose provenance is mysterious even to him. But instead of acting on it, he rides around aimlessly on a tired old horse. The fictional jianghu becomes the real world, and the horse's swaying back and forth our vantage point on it.

The way Han sees it, the masses are all fools, but the emperor is the biggest fool of them yet. The masses will slaughter one another arguing over which came first, the chicken or the egg, and the last person left alive will have forgotten his own position on the matter. Society is structured upon absurdity. Government officials "always arrest whomever they want to arrest," even if they don't know whether they've got the right person or not, "so they take them in anyway, just to check." There's no doubting that this is a martial arts novel, but one suffused with the author's observations about the real world.

Riot in Chang'an City, together with His Kingdom, and the more recent 1988: I Want to Talk to This World, make up an artistic trilogy throughout which entropy reigns. In the latter two, the worn-out horse is traded in for a broken-down motorcycle and a beat-up old station wagon. The horse can never be a gallant steed; the car must always be a bit worse for wear. It's through these decrepitudes that Han Han attempts to seek out the real spirit animating China. "The atmosphere is getting worse and worse, I need to hit the road," begins 1988: I Want to Talk to This World. The terrible atmosphere Han Han refers to here is the social climate surrounding him—murky, perverse to the point of ridiculous; Draconian, without value.

In my opinion, the greatness of his work cannot be explained away by his language or his style. The value of it lies instead in the fact that, in the face of looming social realities that cause everyone to tear one another apart, Han doesn't lay low. Rather, as described in Riot in Chang'an City, he "draws his sword from his satchel and cuts the horse down by the hoof."

In the words of the writer Cao Kou, "While China's contemporary writers typically turn their backs on real life, dance around the topic, or gild the lily, Han Han confronts reality in all its ugliness and futility, and reflects it in his writing earnestly and without adornment... While seasoned writers linger on the "higher plane" of the wider literary scene, Han uses his relatively unsophisticated prose to record the age as he experiences it. His perseverance culminated in his 1988: I Want to Talk to This World; the rest of us, however, have already been 'speechless' for some time now."

Han once told me a story from his childhood. With his legs dangling, he sat behind his father on the back seat of his bicycle. Passing the Town Hall, the young Han asked, "How can our mayor be this corrupt? We need to bring down these corrupt officials. When I grow up, I want to be an honest official and get rid of corruption once and for all." Han did join the fight against corruption in the end, albeit as a story teller—through his stories that would be "a dressing room for the real world."

However, if his work only stopped at that, it would be tedious to read. The vividness of Han's work arises from a bottomless compassion for the world and his idée fixe that life's beauty can disappear in an instant. This notion of fragility is everpresent as he dutifully records both indignities and tender moments alike. In his fiction, Han might linger on a ray of light on the body of a "fallen woman" drawing curtains, or describe a boy who has scaled to the top of the school's flagpole and is wondering to himself about the girl below him in the playground: what year she is in; what class she is in; what desk she sits at.

These tour de force passages might be compared to glimmers of light in a dark box—they represent a spiritual place outside of prosaic concerns. When you get to them, it is like experiencing music amidst static, the burst of warmth in cold blood, a lull in the middle of great speed.

That time I sat in Han Han's car, right after he had spun his car and entered the complex sideways, this second Han Han turned to me and said, "It's a very dull life for these security guards and their pay isn't good. I like to do something to cheer them up."

Han Han's Bio:

Born in 1982, Han Han is a native of Shanghai. A writer, race car driver, magazine editor, and a singer, Han Han won first prize in the 1999 New Concept Essay Competition for his piece, "Seeing Ourselves in a Cup." In 2000, his novel, Triple Door, sold twenty million copies. He went on to publish several more novels, including Riot in Chang'an City, A Fortress, and His Kingdom, as well as a collection of essays. In 2006, he released his debut album, R-18. In 2010, he was chosen by Time as one of "The 100 Most Influential People in the World." The magazine he edited, Party, sold more than a million copies despite folding after only one issue.

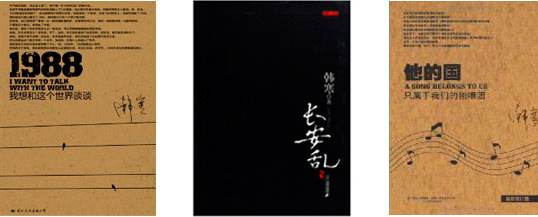

Recommended Works:

1988: I Want to Talk to This World (2010) Han's most mature work to date, this earnest road novel explores the question: If 1989 had not taken place, would the world be a better place? Using a station wagon as the vehicle for this journey, this novel weaves together two plot strands. Strand A is set in the present reality, and describes an encounter with a prostitute, while strand B leads us into the past.

Riot in Chang'an City (2004) A martial arts novel that deconstructs the martial arts novel. The unnamed young protagonist of Riot in Chang'an City finds himself up against all odds. Just as he has matured, fate arranges for him to witness the greatest martial art competition in all the land. At this time, there are two factions, Shaolin and Wudang. Shaolin has the edge over Wudang because, as everyone knows, long hair can be difficult to take care of...

His Kingdom (2009) A story about a kingdom.

17. Zhang Yueran (China) – Removing the 80s label

by Jiang Yan (trans. Li Yuting)

Photo provided by the author

Zhang Yueran has been trying to remove the label for years.

In 2001, Zhang won the first prize in 'The New Concept Writing Competition' while still in high school; it was this prodigious win that gave her the label 'post-80s writer'.

Ever since, three names are mentioned whenever people speak of post-80s writers: Guo Jingming, Han Han, and Zhang Yueran. All three became well-known public figures from winning this same competition.

However, unlike the other two, Zhang was not continually on the front page for dropping out of school—in the case of Han—or plagiarizing—in the case of Guo. Instead, Zhang was a good student, had a good attitude, and was in good health. Disappointed when Tsinghua University did not accept her application as a 'special talent,' Zhang chose to pursue a bachelor's in computer science in Singapore. In her final year, while all her classmates were busy hunting for jobs, she returned to literature, as she later put it: "writing [computer] programs as well as stories".

Several years later, Zhang was still being listed with Guo and Han (as well as Di An and Luo Luo) as the most well-known of the post-80s writers. However, their life paths could not be more different. Guo became more of a businessman than a writer; Han worked hard to improve his image. As distinct from her competition-winning peers, Zhang was the only one devoting her life to literature.

In 2006, provoked by Guo's plagiarism scandal, Zhang unexpectedly announced on her blog that she wanted to get rid of the 80s label she had been stuck with from the very beginning. In the article, Zhang blamed Guo for not taking responsibility for his mistake and for refusing to apologize; it became clear to her that if she and other people continued to keep silent, this mistake would be repeated by the entire generation. She also questioned the influence that the 80s label has had. Specifically, she took issue with the idea that so-called 80s writers were optimists immersing in the creation of literature. Once recognized as post-80s writers, many of them became in cultural spokespeople, commercial tools, entertainment props. She proposed that her generation take the scandal as a lesson. This wasn't the first time the fearlessly candid Zhang had taken the group to task. In an article in Newriting, the literary magazine she founded, she compared the post-80s generation to a group of "flatterers," people devoid of their own opinions, easily incited, eager to follow the crowd, too naïve.

The article wasn't appreciated; instead, Zhang was accused of betraying her contemporaries. In response, she said that she saw the same flaws in herself, and that if the article was considered treason, she was betraying herself too. She urged everyone belonging to the post-80s generation to embrace introspection and change.

Newriting represents Zhang's desire for a 'pure literature'. Instead of being a mere magazine, Newriting is conceived as a book with a central theme for every issue: ambiguity, loneliness, the best of times, escapist philosophy, addiction, and lateness. Collectively, the many Newriting books demonstrate that these modern themes have their place in literature. But perhaps most importantly, Newriting has introduced several outstanding foreign writers to Chinese readers. The very first interview of Sarah Waters in Chinese, for example, was published in Newriting. Other notable features include an exclusive interview with Aoyama Nanae and the works of Janet Vincent.

At the same time, Newriting has published many native writers underrecognized in China. Zhang, who looks to Granta as a model, considers it the mission of a literary magazine to educate its readers by introducing them to new, dynamic work.

It is likely that editing the magazine has taken up most of her time, as Zhang hasn't released any new work since the novel, The Promise Bird, six years ago. She has told young people with literary ambitions that "it is definitely not a good time to succeed in literature. For those who still want to choose this path, you should treat it as going against the grain. You must have strength of mind and be prepared to adapt. At the same time, remind yourself constantly that you are on the path to fulfilling your dreams." In the same spirit, let's hope that Zhang will show us a new book soon.

Zhang Yueran's Bio:

'Fate is playing hide and seek with me, either I catch it or it waits for me.' Zhang Yueran, a Scorpio, was born in Jinan, Shandong, in 1982. While working as a Chinese lecturer at university, her father tried to persuade her to study science, but failed. From childhood, Zhang has liked daydreaming, spending all her time living in a wonderland and trying to turn images into literature. After winning the writing competition in 2001, Zhang started to publish her works in the online magazine Mengya. She is known for the works Red Shoes, Ten Tales of Love, The Narcissus Has Gone with the Carp, and The Promise Bird.

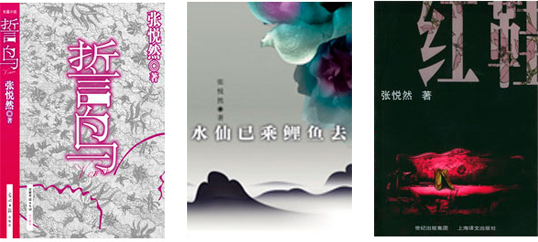

Recommended Works:

The Promise Bird (2006) A Chinese woman finds her way around Southeast Asia after a tsunami makes her amnesiac. Drifting from place to place, homeless and miserable, she falls ill and is sent to jail. To recover her memories, she eventually blinds herself. Zhang herself experienced the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia, where she was doing research. After several days of hiding, she finally returned to Singapore to set to work on this novel of disconnection.

The Narcissus Has Gone with the Carp (2005) 'Is this story about reincarnation?' is the most-asked question by readers of this book. A girl suffering from bulimia is constantly mocked for her unsightly appearance. Badly treated by life, she becomes pregnant and decides to get rid of the baby. However, an encounter with her newly remarried—and pregnant—mother changes her mind. Like in many of Zhang's stories, the protagonist tries to run away from her fate. Will it work this time?

Red Shoes (2004) A man takes a girl under his wing out of remorse for killing her mother. The little girl grows up lonely, indifferent to him and the world, even though he is willing to give up everything for her. When this book came out, this female character's extreme personality triggered considerable discussion among readers; however, it is such extremes that Zhang likes to write about, for they generate great power for a story.

Click here to read Zhang Yueran's short story 'Dirty Rain', translated by Jeremy Tiang for our Jan 2012 issue.

18. Di An (China) – A Tragic Fairy Tale

by Xue Luolei (trans. Li Yuting)

Photo provided by Ben Shi Wen Hua

Di An's short story 'Yuanji' (Parnirvana) is about a man with no arms or legs. But it's neither a cold nor cruel account. Under Di's gentle treatment, the dreary subject matter is skillfully worked into a fairy tale, combining elements of both pathos and joy that recall Hans Christian Andersen's 'The Ugly Duckling'. One might even go so far as to call the story a tragic fairy tale—a "genre" Di tackles in her oeuvre.

Born in 1983, Di An has published five novels and several novellas, including Lili and Yuanji, which are perhaps the most representative of her work in novella form. Since bursting onto the scene with My Sister's Love Jungle in 2003, Di has been writing for ten years now; her latest novel Nanyin: Memory in the City of Dragon—Part Three came out in 2012.

Published when she was only 21, Ashes to Ashes is Di's first novel. A good novel is not only the product of talent; it also comes out of past experience with other literary texts, and deep contemplation. Thus, most young writers debut with a work that oozes talent, but lacks maturity and cool. Ashes to Ashes is no exception. A story of love and hate intertwined, this novel about young people reads somewhat like a piece of juvenilia. Still, Di's signature use of the tragic fairy tale to express the desolate and broken aspects of life with a touch of warmth finds its origins here.

When Di's third novella Xijue: Memory in the City of Dragon—Part One was published in 2009, it had been three years since the release of Desperate Love, her second novel. Her compassionate attention to the protagonist's emotions sometimes draws us too close to the character, causing the novel to suffer from sentimentality. In Xijue this sentimentality is reined in, and the narrative progresses steadily in a manner suited to the placid personality of the eponymous protagonist. Though there is little high drama in the plot, which revolves around a few past and present episodes of ordinary family life, the story effortlessly—and admirably—draws us in. Even if expressly about the trifles of common life, its atmosphere is that of heavenly paradise. In his introduction to the book, Su Tong describes it as "beautiful yet disillusioning," a perfect description of the conflict at the heart of Di's "tragic fairy tales".

Xijue constituted something of a break for Di An, representing a step into maturity for the young author and signaling the beginning of her rise to fame. It was followed in 2010 by the 300,000 word novel Dongmi: Memory in the City of Dragon—Part Two, which tells the story of Dongmi, a willful and stubborn girl who must eventually bow to reality's demands. It is the highlight of her bibliography for many fans, and possibly for the novelist as well.

Nanyin was published in early 2012 as the final installment of the Memory in the City of Dragon trilogy. Here Di An seeks to peel back the veil of the fairy tale and emphasize the tragic aspects of her style. The novel sees the once calm and compassionate Xijue commit murder; Dongmi, formerly an example for others to follow, now invites cold and embarrassed looks; Nanyin, no longer a paragon of optimism and cheer, falters and passes into moral darkness. Di has written leaden, cruel stories before, but never has she plunged so deeply into despair. Yet, even in this darkest of her works, a fairy tale slips through, this time composed by her character Nanyin, who works on it intermittently and brings it to a close at the novel's end. Nanyin's fairy tale, made up of innocent elements (an alien child, a little bear and a tiny fairy) is the ray of light that penetrates this otherwise bleak novel, its single solace and its coda.

Di's next book, the already-announced Mei Lanfang: the Story of an Opera Master, promises to delight, and should only further the reputation of its author, who, from among the crop of post-80s writers, already appears to be the one with the greatest potential.

Di An's Bio:

Di An (born Li Di'an in Taiyuan Sanxi in 1983) was the editor-in-chief for the literary magazine ZUI Found. Her first short story, 'My Sister's Love Jungle', was published in Harvest in 2003, followed by her debut novel Ashes to Ashes, in 2005. A second novel, Desperate Love, came out the following year. It was the publication of Xijue in 2009 that made Di An's name, winning her several prizes, among them the Most Promising New Talent Award and the Chinese Literature Media Award. Dongmi and Nanyin followed thereafter. Bai Ye has praised her work for "expanding the range and depth of youth literature."

Recommended Works:

Xijue: Memory in the City of Dragon—Part One (2009) This may be the best novel to begin your love affair with Di An's work. Compared to the dramatic madness of Dongmi and the cold desperation of Nanyin, Xijue is very mild indeed. With no dramatic story line, it succeeds nonetheless in absorbing us completely, and embedding itself in our minds.

In Memory of Dragon Maiden (2007) Published in 2007, In Memory of Dragon Maiden is a collection of Di An's novellas comprising 'My Sister's Love Jungle', 'Lili' and 'In Memory of Dragon Maiden'. At the time of its publication, most of the post-80s writers were writing novels instead of novellas to fulfill market demand. These three novellas exemplify the elegance of her writing.

Nanyin: Memory in the City of Dragon—Part Three (2012) For a good example of dark Di An novel (which is rare), read Nanyin. Di experimented with a different tone to write this affecting story that unearths the hidden darknesses in man's deepest psyche. Most post-80s writers have failed to pull this off. Di should be commended for her courage.

19. Chen Boqing (Taiwan) – Capturing His Generation's Theme Song

by Jiang Lingqing (trans. Jesse Field)

Photo by Xiao Tu

My memory of my life before reading Chen Boqing (also known as Morris Chen) is as faraway as the "summer before History began," a phrase that opens his 'Circus'. Upon my first contact with Chen's oeuvre, I felt I had acquired a new mental interface through which to process the world. I've become accustomed to this new mode; I keep myself up to date with its developments. Chen demands great things of his work and his rigorous standards have led him to consistently underrate his writing, despite having produced over a hundred essays and stories since he started to take writing seriously in university. However, these same standards have also kept him from following the formula of many young writers who produce collections made up of prize-winning stories; instead, Chen claims that it is only by penetrating the brambled forest of language that proliferates in newspapers, magazines and blogs, that one can, like intrepid video game heroes, climb levels and win fortune.

At first, I thought that the strength of Chen's work lay in his unique writing style. I used to wonder if the thousands of reviews and reading notes accumulated on his blogs, "Guerilla Lecture Notes" and "Clock Wanderer" had colored his writing with the specter of other plots. Only when I read his debut novel, Little City, published last year under the pseudonym Ye Fulu, did I see that he had already begun to establish something quite special: a form of collective memory belonging solely to our generation of Taiwanese, the so-called "Seventh Graders". Little City marked the completion of a project he had labored over for years, in which Chen refuses to submit to the clichéd forms of landscape and language representation present in contemporary Taiwanese writing. Instead, he writes out of personal experience—the writer's greatest asset—to liberate Literature from falsely imposed structures and value systems. In this way, the language of television, the canned writing in official documents, the syntactic potential of text messages, the dramatic conventions of four-panel manga, and even a particular tone of voice used to announce time all become part of his distinctive style—they are, so to speak, the workmen behind the scenes of his little linguistic city.

Many of Chen's pieces are scattered all over the Internet, manifesting different lives depending on when they are read. In 'Circus', a poor city-dweller resists his evictors by tearing down the walls of his own apartment, and using the bricks to build a labyrinth. 'Old Rooms' begins with a series of supernatural events that devolve into an absurd debate between the Japanese and Kuomintang armies, before ending up as simply a grain in the collective Taiwanese imagination—a constructed narrative movement. 'Four Panel Manga' uses the simple logic of manga to explore our flashes of doubt about life. The stories therein are vivid examples of the everyday married to the absurd, and make up a new narrative form, both fantastic and realist, born equally of the past and future. Chen undertakes an archaeology of the present to frame "generational memory" even as he also makes predictions about the direction our island is taking.

Yet what gives his writing the character of an interface is not just the extent, and how distinctively, he invokes the fantastic as a framing device for narrative. More importantly, he gives us ordinary characters fuelled by desperate—even apocalyptic—willpower that turn out to be brilliantly belligerent and wasteful. There are the lovers who enact their doomed passion as nuclear disaster levels the city in the parable-like 'Air Raid Siren.' There is the young man from 'Pool of Courage' embarrassed by his adolescent body, but who, over the course of a swimming lesson, learns the resilience necessary to face the world. Morris Chen's inventiveness renders these characters—so ordinary that they become extraordinary—an ode to his generation. In his stories, simple problems representative of our most formative experiences—obsessing over some tiny matter, wanting attention that we do not get—yield unexpected profundity. With age, we tend to forget these experiences, but Chen reminds us of their place in our lives.

Today, media technology is changing the way people process memory. Chen's narrative investigates those types of memory that can't be captured by text messages or digital cameras, showing, finally, that literature is irreplaceable. Drawing from culture and personal experience, he gives us stories where words never age and narrative is forever written over by the memory of each successive generation. Chen's fierce originality makes him a new model for Chinese writing in Taiwan. To read him is to witness, with great pleasure, an immense talent committed to encapsulating his generation, to capturing, if you will, its theme song: how this world breathes—and blasts by faster than any eye can see.

Chen Boqing's Bio:

Born in 1983, Chen is currently a graduate student at National Taiwan University's Graduate Institute of Taiwanese Literature and is known for both his essays and his fiction. His debut, Little City, won the Jiuge Two Million Publishing Award for Best Novel. One of the most noted of the "Seventh Grader" writers, Chen has been selected for numerous anthologies. With his no-holds-barred attitude, he has plumbed the possibilities of fiction, exploring various technologized forms of writing. More than a pioneer of a new aesthetic, Chen is also a shrewd observer of changing undercurrents of society. In his latest work, First Municipal Combat Elementary, he investigates how fiction might thrive outside of strict cause and effect.

Recommended Works:

Little City (2011) Beginning with elements of "Seventh Grader" collective memories such as university entrance exams, the television show Nights of the Rose, and Tamagotchis, this novel investigates how memory and narrative can reverse the structure and movement of a city. Little City takes the observation of the changes in Taipei as its theme, using realistic setting and a cinematic style, with some paragraphs resembling movie cuts.

'Cell Phone Story' (2007) Constrained in its descriptions by the 70-character-limit of text messages, this story constitutes a new direction in literature. The novel, about the new generation "overwriting" the old, is ultimately optimistic about the adaption of current technology to literary writing. While it seems at first to have been written quickly, it is full of intricate detail and demonstrates the versatility of contemporary Chinese writing.

'Circus' (2010) Opening with a public notice, this story takes a news item all too common in recent times—"Elderly Flat Resident Protests Government-Ordered Eviction, Demolition"—and delivers a fantastic outcome at the same time as it wryly comments on real life. With humor and absurdity, Chen depicts a group of poor city dwellers protesting against power, in which the very act of protest becomes a romantic outpouring of warmth towards life.

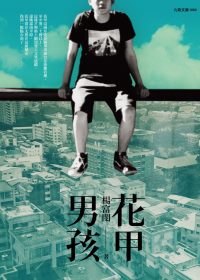

20. Yang Fumin (Taiwan) – Raise a Tear for the Fear of Death

by Zhai Ao (trans. Jesse Field)

Photo provided by the author

First, I must confess that, yes, Yang Fumin is my classmate in graduate school. We talk about our lives, we discuss literature, and sometimes, in the dark of the night, we bring out the even darker sides of ourselves, our deepest inner thoughts. Consoling each other helps us sleep better. And yet, I still don't understand him. He's like a water current, forever in flux. There's no knowing where he's coming from or where he's going (in this respect, he thinks the same way he leaves a room). Commenting on Yang's story 'Speed of Flow', Zhou Fenling, his teacher, writes, "He goes too fast, hurries too much." I feel this is because Yang is cocksure, working hard to be out front beyond the crowd, the better to tell us all what's ahead.

Which is...?

Death—just that, nothing more.

This is why from the beginning of his debut collection Sixty Year Old Boy, Yang is like Detective Conan, always coming back to death. Some stories are dressed-up, somewhat wordy funeral processions ('Would that this Sleep could Last', 'Didn't Hear That', 'There's Ghosts'); some feature sudden and unexpected disasters ('My Name is Chen Zhewu', 'Constellation Number Five'); still others describe the moment separating life from death ('Genuine', 'A Day on the Spirit Sedan,' 'Sing a Song For You to Hear', 'Sixty Years Old'). How was he able to martial differing narrative structures around a common theme to craft a unified collection? It is precisely this fundamental yet irresolvable theme that drives authors still using writing as a means of exploration. As Margaret Atwood once said, "All writing of the narrative kind, and perhaps all writing, is motivated, deep down, by a fear of and a fascination with mortality—by a desire to make the risky trip to the Underworld, and to bring something or someone back from the dead." Still, there is something different about Yang. He brings to the table the curiosity of a newborn calf, and under his pen, death rarely takes the form of a violent extortionist. Instead, by writing of illness and the degeneration of the body, as well as the tiniest details of funerary custom, Yang slows the speed of descent towards death, thus inviting the reader to contemplate the relationship between body and spirit, between life and death, between "I" and others. And as the God-author of the stories, Yang has time to observe: what is all this about? What is death anyhow? In these works, death is not only the destruction of a body, but also a turning point for the living. The dead might be done, but what are the living to do with themselves?

But the price of a servile death is that it is no longer terrible; feelings surrounding death lose value. We never get to see Conan alone and in mourning; everyone just wants to know the cause of death: was it cyanide? Was it a murder behind closed doors? And yet, Yang pays us back with eloquence. By "pay back" I don't mean to say that he uses style to conceal substance, to hoodwink. Rather, I mean that his writing never strays from the mark. Tangled up as it is with the polysonority of Taiwan and of languages from other countries, it comes forth so mellifluously that the reader finds it irresistible—and if the writing convinces, as they say, feelings will flow. The celebrated nativist writers of the past recommended the use of native language, but it always made the writing stilted and unmanageable; confronted with breaks in voice, the reader's pace slowed. Yang's writing, on the other hand, marks its trajectory like a bullet. However, it deviates from Newton's first law of motion in that its action is not derived from some other action, but wholly its own. Still, insofar as literary influences exist, Yang is a combination of an elevated Wu He and a coarse Chu T'ien-wen. As evidenced by his subject matter, Yang's love of his native land is probably the most pronounced from among the Seventh Graders. His hometown of Tainan may be full of pomelos and water chestnuts, but it is also full of stories, and these are the material from which Yang draws to create his first works. Compared to others without first-hand experience of Tainan, Yang is uniquely endowed. Chu T'ien-wen's harrowing "It's so good to have a body," becomes, under the pen of Yang, the moderate "It's so good to have a hometown." And even though the stories of his hometown represent capital, they still take time to put on the market; how to resell it without a loss in value is the experiment of the Seventh Graders.

Last year, the novelist Li Yu, who doesn't shy away from the title 'prose stylist' (a term especially associated with Shen Congwen), returned to Taiwan for a short professorial stint; Yang was her teaching assistant as well as student. What advice did Li Yu have for him? Is China not the canon itself?

Pursuers of hometown mysteries must leave their homes first before they are able to begin the pursuit, as Lu Xun left Shaoxing, Shen Congwen left West Hunan, or Chung Li-ho left Meinong. Whether Yang will be inducted into the same Hall of Fame is a question that will have to wait. If Yang does not begrudge being grouped with Li Yu, if he makes his home in the unknown that lies ahead, then he may create countless possible homes through his countless possible writings. In the end, writing stitched to perfection may announce a return, but also signal that there is finally no return to speak of.

Yang Fumin's Bio:

Born in Tainan in 1987, Yang Fumin is currently a graduate student at the National Taiwan University Graduate Institute of Taiwan Literature. In 2010 he published the short story collection Sixty-Year Old Boy—a stellar example of how a Seventh Grader author might carry on the vitality of the native Taiwan language via a grotesquery of Taiwanese scenes. In these stories, sound is an element not to be overlooked, from the suonas and gongs of funeral processions, to current popular songs, the Taiwan-inflected Mandarin Chinese of the new generation, and the Chinglish of ABCs, which all add up to a writing full of noise and bombast. Recently, in his Liberty Times column "Blustering," Yang has written on the boldness and lack of restraint among youth, on the old ways of Tainan, and reflections on how little he understood the world in his youthful ignorance. In his new work, tentatively entitled What Happened to the Huang Family, the passing of the Old Uncle, the last member of the Huangs, closes a chapter. Yang, though himself not yet 30, writes from the point of view of the Huang family's old soul, tracing, in this unconventional historical narrative, the memory of the clan, an account of how its members got scattered, how the number of its ghosts grew. It is currently under serial publication.

Recommended Works:

'Genuine' (Collected in Sixty-Year-Old Boy, 2010) Winner of the first prize in the Fifth Lin Rung San Awards for best short story. 'Genuine' recounts how Mama Shuiliang, who had depended on her husband her whole life, steps onto a magnificent ornamented automobile, shiny hat on her head, to ride wildly in a circuit around greater Tainan making the traditional announcement of his death, and presenting sights and sounds that constitute a microcosm of all Taiwan. A funeral procession that sets out somber and inauspicious but is filled with joy by the end. The story is particularly good at conveying the personality of Mama Shuilang, whose high spirits are just like the "Taiwan Jacana," a bird featured in the story. Yang's facility for mixing language is plainly evident here: not only is the story a kitchen sink filled with every kind of language, it is also a lake of vitality, rippling cultures old and new.

'What Happened to the Huang Family' (Salt-Zone Literature, bi-monthly, issue 30, October 2010) Old Uncle, a despicable defector from the "Huang Family," has made the pursuit of his political ideals his life's work from the time of his youth when the nativist movement first began. Nevertheless, he dies a depressed man. Only in Old Uncle's last moments do we discover his greatness. Narrated in first-person, the exposition deals with Old Uncle's book collection and remaining personal effects, tracing the past of a group of young revolutionaries out of dying last embers and giving it a framework that in the end aligns with the island's political developments. The lives they transformed turned out to be their very own! Once again, Yang writes of death, only this time death is closer than ever. On the other hand, the intolerable pressure that death puts on the living is swept away. Where do dead people go? Can the living go there, too? In one fell swoop, Yang overturns the cliché of the resolution-filled happy ending, concluding instead: "They're gone!"